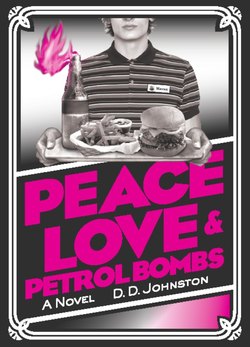

Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Whenever you question how something came to be the way it is, and especially if you try to change it, someone will tell you, “The world is just that way.” But the world is not just that way; there are reasons why things are the way they are. Take Benny’s Burgers. At Benny’s Burgers there is a procedure for everything—I mean everything. There is a procedure for how you wash your hands; there is a procedure for how you fill a mop bucket; there are procedures stipulating which side of your shirt you wear your name badge on and how you tie your apron. There are prohibitions on certain colours of socks and regulations on how high you can stack boxes (boxes of fries should be piled five high; boxes of fruit pies should only be piled three high). You’re allowed to cook nine hamburgers in a batch but no more than six chicken burgers. Why? Because that’s the procedure. Why? Because it’s just that way.

Wrong. Benny’s Burgers is not just that way; there are reasons why a small chain of Italian ristorantes became a multinational burger conglomerate. Benny’s began life in the Bronx borough of New York City. In those days it was Benito’s: a family place where the pizzas were cooked in a stone oven, the carbonara was recommended, and the seafood was surprisingly good. Sonny Alligarta ate there in 1958 (he had the spaghetti marinara) and he liked everything about it. He liked the precooked sauces and the pre-boiled pasta. He especially liked the teenage girls who served him from a numbered menu. In fact, he liked Benito’s so much, he bought it.

Sonny dreamed of expanding Benito’s across the continent, envisaging a time when basil and red wine would be indispensable to the diet of every American, but in 1963, a snapped fan belt left him stranded and hungry in Codicioso. As far as Sonny could figure, Codicioso only had one eatery. The burger he bought cost fifteen cents and was ready made when he ordered; served on a toasted bun, with a slice of cheese from a packet, it tasted like it had been sitting in a hot cabinet since before the Civil War. They were serving this shit and people were queuing up to buy it—the future, he decided, was burgers.

Sonny didn’t mean to disrespect his Italian heritage but Benito’s? It was a bit… un-American. So he changed the name to Benny’s. He replaced the chefs and waiters with children, college students, single mothers, and first-generation immigrants. He bought the cheapest ingredients and for two years he undercut every greasy spoon in New York. Soon you could get a Benny’s Burger in Chicago, Sydney, Shanghai, Islamabad—even Dundule—and with his fortune, Sonny found celebrity. Like Mc-Donald’s chief Ray Kroc, Sonny was moved to publish his autobiography, but while Kroc’s legacy is illustrated in poetic quotes that capture the Zeitgeist of post-war America, Alligarta’s statements have proved more controversial. Where “We sold them a dream and paid them as little as possible” is attributed to Kroc discussing McDonald’s staff, Alligarta is reported to have said of Benny’s employees, “We worked them like dogs and paid them like monkeys.” Kroc’s autobiography is filled with insights such as “It was not her sex appeal but the obvious relish with which she devoured the hamburger that made my pulse begin to hammer with excitement,” while Alligarta’s memoirs bluntly recollect, “The ketchup dribbled on her considerable cleavage, and it really gave me the horn.”

And yet, by 1998, Benny’s employed over a million people in over a hundred countries and annually spent over two billion dollars beaming Big Benny’s twisted world-view into toddlers’ underdeveloped minds. When we say something is just that way, what we’re really saying is that we don’t know, or can’t be bothered to explain, why it is the way it is. To try to understand McDonaldization (and Benny’s hated the term, preferring to describe McDonald’s as “Bennyized”) we’d need to consider the logic of capitalist production, investors’ demands for profit, and the resultant urge to maximise the extraction of surplus value from labour. We’d also need to consider the genealogies of Fordism and centralised scientific management, how the Fordist method of production was implemented to break the power of the organised working class, how the State turned machine guns on the unemployed during the 1932 Ford Hunger March, and so on.

But these are not the sort of events that corporate historiography records. Every year, Benny’s marks the anniversary of Alligarta’s investment by sending each restaurant a frozen cake. Senior managers make morale-boosting visits to the shop floor, and in the evening they organise team quizzes where all the questions are about the optimum temperature for cooking fish burgers or how high boxes of fries maybe piled. For Kieran Hunter, Second Assistant Manager, Founder’s Day was better than Christmas.

The day I met Spocky, Kieran stood pondering his wristwatch, sweating in the late-morning heat. Benny’s divided their staff into those they trusted to tie a neat Windsor and those who would forever need to wear a company-issued clip-on strip of polyester. Whatever ignominies the rest of life might inflict on him, Kieran would always belong to that stratum of the corporation trusted to tie their own ties. “PACE, yeah?” he said as I opened the door. “Punctuality. Attitude. Customer focus. Enthusiasm. Yeah?” The store was quiet and the tables had been wiped streaky with antibacterial spray. “You are… seven minutes late, yeah?”

“Am I?”

“Yes,” he said, exhibiting his watch. “And, I’ve checked your file. This is your third late arrival and you know what that means, yeah?”

“I get to keep your watch?”

“It means a formal written warning.” He wore a new cap with a high dome that made him look like an extraterrestrial cone head. Above his mouth, his freckly face was decorated with a light ginger down. These few wispy centipede legs were the only evidence of his ongoing attempts to produce a moustache (facial hair was banned at Benny’s, but they permitted groomed moustaches). “Well, what you waiting for? You’re now eight minutes late. Yeah?” He took a heavy set of keys from his pocket and lobbed them in his right hand.

The staff room was a small square box that contained thirty lockers and a table for two. There was an ironing board (someone had stolen the iron), a broken video player, and a television that was trapped on BBC One. The floor was strewn with plastic cups, polystyrene foams, and cardboard fry cartons, and the room had a strange smell, as if a diseased animal had died in one of the lockers. There was only one other guy in the room; I didn’t recognise him, and he didn’t acknowledge me. He appeared to be reading a book. “Is the TV knackered again?”

“I don’t know,” he said, turning the page. He wore a black trench coat, stone-washed jeans, and cheap trainers. His head was shaved and he wore spectacles with a thin black frame.

“What you reading?”

“It’s just a novel.”

“Let’s see,” I said, grabbing it from him. “The Dispossessed,” I read, making it sound stupid. There was a picture of a planet on the front. “What’s this, Star Trek or something?”

“No, it’s about this alternative civilisation. These people set up a utopian society on the moon of—”

“Sounds shite,” I said, throwing my jacket in an empty locker.

He reached for his book, thumbed to his page, and scratched his neck. That was when Raj crashed the door against the lockers. “Wayne, motherfucker!” He made to punch fists but I messed up the timing and his knuckles landed in my open palm. “Alright?” he said as we clasped hands. “What sort of time is this? Listen man, we’re gonnae be busy as fuck the day so I’m gonnae need you tae work your ass off, aye?”

I tugged my cap on and saluted. “No bothers, chief.”

Raj’s real name was Rajiv, or Rajesh, or Rajani. We called him Raj because it was easier. Raj wasn’t allowed his own tie, but he did get to wear trousers with pockets (a licence denied to regular staff). He was alright, Raj—alright for a Paki. That’s probably what they’ll put on his gravestone: “Here lies Rajesh (or whatever his name was). He was alright for a Paki.” Although he had contended with it all his life, at times you could see that Raj still struggled to accept the Dundule understanding of geography: the population of Dundule maintained that Pakistan was a massive country, starting near Bucharest and stretching across Turkey, North Africa, much of the former Soviet Union, the Middle East, the Indian Subcontinent, and Sri Lanka. “Hoy, who the fuck are you?”

The new guy looked up from his book. “I’m Owen Noonan. I just started today.”

“Well, shit, get your uniform on!”

“They never gave me one.”

“Machod, were you gonnae sit there till one grew on you?”

“Nope, I’m off at five.”

“Oh Wayne, we’ve got a smart one here. What you reading?”

“Star Trek or something,” I said.

The new guy showed Raj the cover. “No, it’s about these people go to live on the moon and—” He bent over the table with a phlegmy cough.

“Can you speak Klingon?”

“Captain Spock, eh?”

“I’ll get you a uniform. I’ll send it to you in the transporter beam.” You could hear Raj laughing as the door swung closed.

“He’s awright for a Paki, eh?” said Gordon, crashing the grill tongs onto the grease trap.

“What?”

“I says Raj is awright for a Paki.”

“Aye, suppose.”

Gordon had started at Benny’s two months after I had, but we’d known each other since school. He’d been planning to follow his uncle into the jewellery trade, but when that didn’t work out, I persuaded him to join me in the burger game. I enjoyed working with Gordon even if it was hard to talk above the background noise—metal trays cymballed steel surfaces, grills hissed, bun spatulas clattered, fry baskets crashed through the automatic racking machine. “Someone hit that fuckin’ timer!” shouted Raj because the “Time to wash your hands” beeper had been ringing for two minutes—preep preep, preep preep, preep preep—like a phone call that nobody wants to answer.

“Woah, where you going?” said Raj, stopping Lucy as she walked through the kitchen.

She paused by the milkshake machine, holding her apron. “Kieran says I’ve to count a float.”

“Kieran!”

“What?”

“Did you tell Lucy to count a float?”

“Yeah, she’s going on tills.”

“Fuck off,” said Raj, brandishing the floor plan. “I’ve got Lucy and you’ve got Captain Picard through there.”

Kieran studied the plan and stroked his tie. “Okay, but whose shift is it, yeah?”

“It doesnae matter whose shift it is; you cannae steal my staff just cause you fancy them.”

Lucy looked embarrassed, and Kieran pulled the keys from his pocket, tossing them from one hand to the other. Everybody fancied Lucy. “If you’d ever been on the ABC shift supervisors course then you’d know about PROSE—Plan, Review, Organise, Supervise, Encourage. There’s the plan, yeah? Here’s me reviewing it, ‘Hmmm.’ And here’s me organising: ‘Lucy, you’re on tills today.’ Okay?”

The milkshake machine had been making an enteric growling noise, and now Raj removed the lid and peered inside. “Buzz!” he said. “Get us some shake mix!” He turned back to Kieran, wielding the lid like a shield. “No danger are you swapping Lucy for that prick. No danger.”

“Raj, at the end of the day, I’m the shift runner, so all the staff, including you, are under my jurisprudence, yeah? It’s not about any one area; it’s about maximising sales and improving the performance of the whole team. Yeah?” Kieran tossed his keys higher, caught them, and slipped them into his pocket. “Go on, love,” he said, patting the small of Lucy’s back. “Put your apron away for me.” So Lucy strolled past the chicken vats and paused by the backroom sinks, where Spocky was attempting to clock in. I watched as she said something, took his card from between his fingers, swiped it, pressed yes, and left him to survey his new environment.

Spocky was so slightly built that at a casual glance he appeared taller than he really was. Perhaps this was why he’d been given enormous polyester slacks that trailed in the seeping sink water. Holding up these circus clown trousers, Spocky stood in his red and white striped uniform, gazing at the swamps of grease beneath the fry station. He studied the polished white walls, the cascading faces of stainless steel, and the mayonnaise-crusted ceiling tiles. Meanwhile, above a stack of defrosted buns, the electric fly trap sparked blue, incinerating another victim with a short fizz-crackle.