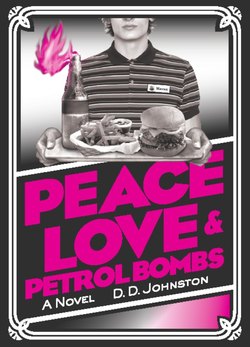

Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

I didn’t see Deanne until November 1997, by which time she had given birth to a small golem-like creature. She called it David and spoke to it as if it were a person. Sometimes she paraded it, as though the pram was an open-topped bus and the creature was the Scottish Cup. “Is he no just gorgeous?”

“Aye,” I said, wondering how such a thing could have happened in so brief a time. A few years later, when Gordon told me Deanne was dead, I had the same reaction. “I saw her in town only last Monday!” I said, like I was amazed the Grim Reaper hadn’t been carrying her shopping.

Deanne had found Giorgio in bed with a sixteen-year-old hairdresser from Stirling and had immediately forgiven Gordon and me. The one time I mentioned Jason, she shrugged and said “That’s in the past.” Meanwhile, I’d met Kit at work. Kit, with her blonde pigtails and pale face, had started working at Benny’s in March ’97. When you live in a small town, everyone is the friend of someone you know; the local papers are full of tales of serendipity, of long lost brothers who lived next door to each other and men who found their mother in law’s wallet on the High Street; we all live like celebrities, worrying who will recognise us if we go to the shops in old clothes. So it shouldn’t have surprised me that Kit and Deanne had grown up on the same street, and had, at one time, been best friends. Kit knew that Deanne and I had slept together, but was satisfied that all that was in the past. Time had moved on: Deanne was now a single parent, living in a three bedroom council house and struggling for cash; Kit and I were keen to cohabit... living together made sense at the time, but it turned out to be a disaster.

All through the summer of ’98, David screamed. He screamed every morning, with admirable regularity, the way some adults go jogging or watch Breakfast TV. “Look, David! It’s the Teletubbies! Look, David!” You’d have thought he’d need to pause, draw breath, review what this tactic had achieved. “Gonnae shut the fuck up! I’m fuckin sick ae you!” shouted Deanne.

I don’t know how Kit slept through this shit. On the day I met Spocky, I sat on the edge of our bed, and she rolled away, trying to smother the morning with our duvet, as the heat broke through the curtains. “Have you no got work?” she said.

“I’m just going now.”

“Stupid work.” Even in the summer, Deanne’s flat was so wet that mould grew on furniture and wallpaper peeled. One time, the council sent a workman. He painted the bathroom and then watched with us as white drops of watery paint plopped from the ceiling, drawing a polka-dot pattern on the carpet.

“Fuckin shut up!” I heard Deanne’s footsteps and the bathroom door slammed and the walls shook and a bottle of CK Be tumbled onto the carpet. There wasn’t much in our room: an old television with an indoor aerial sat on a Formica-covered chest of drawers; an unstable shelf supported a cluster of toiletries and a singed plastic rose. The rose was the first thing I ever bought Kit, but one night, during an argument, I burned it with my lighter. It takes time to accumulate possessions. Eventually, the past sticks to you like fluff to Sellotape dragged across a dusty suit.

In the living room, a packet of Super Kings lay on the coffee table, and an American woman shouted about sun protection on GMTV. David was harnessed in his bouncer, hanging in the kitchen doorway. His pink face trembled as the sun bounced through the windows, greenhousing the room. I started to tiptoe across the carpet, as though I was an art thief and the naked baby was a security system, but when I got halfway to the kitchen, his mouth opened. I stopped and smiled but the mouth opened wider, until I could see the whole dark passage, so I stood there, grinning. David filled his lungs, held his breath, and screamed. “David, dinnae. Fuck. Please don’t. D’you want this?” I offered him a plastic toy with a squeaky button and a mirror. He threw it at me and screamed louder.

“What ye done tae him?” asked Deanne, when she returned from the bathroom.

“Sorry,” I said. “I was just after a glass of water.”

“David! David! Wee man. Ssshh. Bouncy, bouncy. There you go. Shhh. Shut up!” She unclipped him from his harness and laid him naked on his mat, sprawled helpless like a crab on its back.

“Right, Wayne, you’re on buns. Buzz is dressing, Gordon’s on grill. And train Captain Picard here, aye?”

“Owen. My name’s Owen.”

“Doddy! I’ve two chicken burgers left! Gie me three runs of six, two beanies, two fish, start holding two trays of chicken.” It was the hottest day of the year and the kitchen already stank of sweat. “Wayne, I need a continuous pull on Big Bens and Cheese. Come on, cook me some food or I’m gonnae get in shit.” This is how Benny’s works: the “I’m going to get in shit” effect. The business functions because everybody is held responsible for those below him. If it’s your second week and a new starter is sweeping the floor with her apron on, you have to correct her. If you don’t then the store manager will complain to the shift runner, the shift runner will take it out on the floor manager, the floor manager will shout at the team leader, and the team leader will bitch at you. Belatedly, you’ll ask the new start to take off her apron. “Sorry,” you’ll say, “it’s just that if you keep it on then I’m going to get in shit.”

“Why?”

“Dinnae ken. It’s just the procedure.” The next time she has to sweep the floor, she’ll anticipate rebuke from even her lowliest colleagues. She’ll self-censor. In this way, the surveillance becomes panoptical.

Raj exemplified the most successful management strategy practised in Benny’s: he divided the plebs into a favoured section of predominantly experienced workers and a sub-class of inexperienced or socially-compromised novices. The favoured section was privileged with lenient discipline and exemption from the most awful cleaning tasks; the sub-class was universally pissed on. When Raj said “Cook me some food or I’m gonnae get in shit,” the favoured section philanthropically policed the sub-class. In these times of disposable labour, the relatively unproductive sub-class can do little to disturb this mechanism.

When recruiting managers, Benny’s had traditionally favoured ex-military personnel. By the turn of the millennium, however, the totalitarian style of management was losing favour. Although the old regimes appeared to be in control, they were actually more susceptible to rebellion than the modern, comparatively liberal systems built on division. There may be truths about society contained somewhere in these observations. At Benny’s, however, it was hard to develop such a train of thought. For example, consider the life of a bun man. A beeper decrees when toasting should start, a buzzer stipulates when it should end. There are two toasters to be worked on overlapping cycles, and the bun man’s timing is sometimes regulated by a corporate apparatchik with a stopwatch and an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. And yet, at Benny’s, bun toaster is as good as it gets. Take the poor dressings guy: he’s got eighteen seconds to apply condiments to nine buns—a wet slice of pickle, squirts of ketchup and mustard, and a pinch of the onions that come dry in a packet. And the dressings guy is a labour aristocrat next to the grill man. Every time the bun toaster sounds, the grill man must squeeze on a plastic glove and place the frozen discs of meat in the patterns demanded by a plaque above his head. Then he needs to close the grill, initiate the timer, and remove the glove before the lid of his other grill starts to rise. In four seconds, he’s supposed to sprinkle salt on every slab of meat and shovel the meat onto the dressed buns; then he’s supposed to scrape, squeegee, and wipe the grill, retrieve the plastic glove, and lay another pattern of meat. He has forty-six seconds to complete this cycle.

The only escape from this is to cook so much food that the production caller yells, “Enough!”

“Gie me a hold on everything,” said Raj, whose table was now congested with trays of unboxed burgers. “Clean the place up, come on!”

So much lettuce had been strewn on the floor that it looked like a lawn was forcing its way through the tiles. White cloths were dyed yellow with mustard, and every surface was smeared gory with ketchup. On the finger-marked stanchion of the bun stand, a slice of cheese was peeling from its right corner, and somehow a sliver of pickle had stuck to an overhead strip light (where it slowly dried, threatening to launch a kamikaze bombing mission). Raj surveyed the devastation. “Hang on, where the fuck’s Captain Spock?”

At Benny’s, the stock areas are called The Cave. It’s where you go for a private conversation or a five-minute skive. You stand in the stock room with one hand in a condiment box, ready to remove something as soon as the door opens, and if you really don’t want to be found, you go to the back of The Cave, past the bulk Coke and syrup lines, and into the chiller. That’s where I found Spocky. He was sitting on a box of shredded lettuce, reading his book in the sulphurous light. He didn’t hear me open the door, but as I pushed through the curtain of overlapping plastic slats, he stood up, leaving an incriminating dent impressed on the cardboard box. “What th—”

“It’s s–so hot out there.”

“Are you not cold in here?”

“It’s not too–too b–bad actually. I was getting a b–b–bit worried about the oxygen.”

“You’re not right in the head.”

He nodded in vague agreement and coughed into his hand.

“Get your arse back in there.”

“Wh–why?”

“Why? Cause you’ve gottae do some work.”

“Wh–why?”

“Cause that’s just the way shit is.”

After work, I said to Kit, “Let’s climb Breast Mountain. Come on, it’ll be quality.” From our window, the hill looked rubbery in the shimmering heat. “Come on, we’ll take the cider; we’ll watch the sunset.” It was one of those rare hot days, when radios play outdoors and men in shorts wash cars. Parents cleaned mud from paddling pools. Sweaty kids rested bikes against shady walls. In the sunshine, teenage girls lazed in bikini tops, wearing beach towels like sarongs.

Breast Mountain was a sort of no man’s land. It was a border zone between city and country, between this time and the past. Weeds colonised bags of sand and gravel. Slugs burrowed in the slashed foam seat of an abandoned JCB. A woodpigeon took off, exploding balsam pods and downing helicopters as it beat through the branches of a sycamore tree. We crawled through a gap in the fence, ran through nettles—hands up so they didn’t get stung—and then we followed the old train line to where it met the canal.

The canal was filled with bottles and overrun by chickweed; you could fall into it if you didn’t know it was there. The mooring bollards were camouflaged in the undergrowth, and rosebay willow-herb sprouted purple through the loading stage. A bit of everything that ever happened in Dundule was buried here. Refrigerators were dug into the hillside, and burned out cages of cars were charred with rust. There was a roofless warehouse, layered with graffiti, and an industrial chimney stack, poking through a tumble of its own bricks. There were limestone steps curved by generations of walking, and overlooking it all, the big wheel of Brandon Colliery remained suspended, still in the sky.

The “Mountain” was a conical slag heap half-covered with hogweed and docken. Your feet left impressions in the rubble, as if you were climbing a sand dune. Kit told me that she once had sex on the far side, near the bottom, where the gorse bushes had found enough soil to grow. I told her that I smoked my first joint at the top; I recalled leaning back to watch the street lights shiver over Dundule, pretending I was having fun. We agreed that neither extreme skiers nor ice climbers know the risks of sledging Breast Mountain on a plastic tray.

But from the bottom, we could see that a group of boys had already claimed the summit. They were shouting and kicking each other and laughing and acting angry and kicking each other and laughing again. Their shirts were open and they stared razoreyed into the sunshine. Bottles of Becks flashed in their hands. We stopped and waited for a minute, not yet ready for home but not sure what else to do. That’s the thing with these rare hot days: everybody agrees you must make the most of the weather, but nobody’s sure how. The beer dehydrates us, the sun burns our shoulders, the insects crawl on our picnics; by five o’clock, the day has betrayed us.