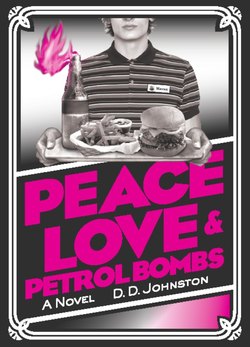

Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

Listen, the only good thing about Benny’s was the craic you could have with your colleagues. Now, looking back from beyond a train wreck of friendships, I’m nostalgic for this teenage camaraderie. When I think about Dundule, I think about Gordon: Gordon, aged thirteen, swaggering into school with tramlines shaved into his head; Gordon, on his first shift at Benny’s, returning from B&Q having failed to buy a tub of tartan paint; Gordon, in full Highland dress, marrying a girl who was, technically, his sister (I know! I know!); and Gordon, departing on some mad odyssey, leaving me to deal with the police. I think about Kit, too. I met Kit at work, but she soon became my girlfriend. The last time I saw her, she was pregnant with someone else’s child, but at one point, Kit and I thought we were going to get married. I think about Buzz, who could get you any drugs you wanted, and Spocky, whose real name, Owen, I almost never used. But most of all, perhaps, when I think about Dundule, I think about Lucy.

Like me, Lucy only scooped fries part time. During my second year at Benny’s, I was re-sitting my school exams at Dundule College of Further Education, while Lucy was already at university, halfway through a sociology degree. It was Lucy who persuaded me onto the politics course at the University of Central Scotland. At that time, Lucy could have persuaded me to do just about anything.

The first class I ever attended was halfway through my first term. My arm was in a sling (I’d been stabbed the week before), and though I was late, the class hadn’t started. We were in room 7G in James McPherson Tower, Melvyn Macveigh’s room, where, because Melvyn Macveigh taught Marxism, the desk-graffiti said stuff like: “Dyslexics of the world untie”; “Academics of the world unite: you have a world to win and nothing to lose but your chairs.” At ten past the hour, Macveigh strode in without apology and slapped his briefcase on the table nearest the door. “It amazes me that they entrust a train company to a man who considers a hot air balloon a desirable mode of transport. Right, what are we supposed to be doing? Ah, I think I’m supposed to stimulate you with this handout.” In brown cords and salmon shirt, he slithered around the rectangle of desks, placing an A4 sheet before each student. When he reached me, he paused and whispered, “Politics and society?” as if circulating profiteroles. I nodded and he affected surprise, rubbing his head as he returned to his desk. “Miles Austin? No? Ashley Zechstein? Wayne Foster?”

“Aye.”

“Ahhh!” he said, as though a long-standing mystery had been contentedly resolved. “Bene qui latuit bene vixit, I suppose. Shall we have a moment to digest this handout?”

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, revolution in Romania and celebrations in Wenceslas Square, the USSR ceased to exist at midnight on the 31st December 1991. With the categorical refutation of Communism in Eastern Europe, has the spectre of Marxism finally been exorcised? In 1991, the Wall Street Journal was less sure: “Marx’s analysis can be applied to the amazing disintegration of communist regimes built on the foundations of his thought but unfaithful to his prescriptions.”

“Well?”

“...”

“...”

A plump girl in a stripy sweater clutched her Beginner’s Marx; a mature student sighed, rubbed his beard, and squeezed the bridge of his nose; a boy in a rugby shirt thumbed that month’s Economist. With every moment that passed, the chair creaking, heating humming, background noise grew louder, until you imagined you could hear breaths and heartbeats, and you looked at Melvyn Macveigh, who continued to stare out the window, happy to wait for the silence to crescendo.

“...”

“...”

It was a freckly boy who cracked first. “It’s like, it doesn’t really matter, you know ?”

“Really?” said Macveigh, distracted from the world outside.

“It’s like, kind of basic and old fashioned? Like it’s stuck in all this worldly… you know? It’s like we’re all talking capitalism and communism, and none of that matters, none of that’s... Is it? Like Buddhism, you know?”

The older student leant forward. “So are you saying Marxism’s an inherently homogenous doctrine? A modernist metanarrative grounded in Enlightenment epistemological certainties and incompatible with a pluralistic world?”

“No. I’m saying, it’s like… I spent my gap year in Nepal, right—”

“Woah-kay. Thank you,” said Melvyn Macveigh.

The heating changed gears.

“You can get this book from Waterstone’s,” said the plump girl, exhibiting her Beginners Guide, “but I still can’t see how this is relevant to the modern world? Like, which employer’s going to care whether you understand ‘Historical Materialism’?” She mouthed the phrase as though there was a chance the words would give way and plummet her into a valley of ridicule. “Besides,” she continued, “there are definitely easier topics for the exam; I mean, it’s in the same unit as the transformation of the Labour Party, isn’t it?”

Melvyn Macveigh was trying to fix something on his watch.

“And it’s never going to happen again, is it?” said the boy in the rugby shirt.

“Oh no. Not here at least,” said Macveigh. “The climate’s too inclement for marching and demonstrating and all that.” As if to prove his point, a gust of wind shook the pre-fabricated tower, triggering an avalanche of plaster.

“I still think his ideas are important to discuss,” said the mature student, stroking his chin. “I mean Marxism, more than anything else in the philosophical canon, sort of shapes contemporary discourse, doesn’t it? It’s like Derrida says: ‘We are all heirs of Marx.’”

This began a pattern which lasted throughout the academic year: every week, the mature student was distinguished from his classmates, the tutor, and the creaking post-war tower, in that he looked like he wanted to be there. As the only person who had done the reading, or had any interest in discussing the topic, the mature student was often driven to internal debate: he would raise a question, listen to the silence for two minutes, and eventually answer himself. On other occasions, provoked by boredom, perhaps, Macveigh would pick on the person who was trying hardest to avoid eye contact. “Mr. Foster, do you wish to contribute to this vibrant debate?”

“...”

“Prospects for Marxism in the twenty-first century?”

“Well… pretty shabby, I suppose.”

“‘Pretty shabby, I suppose.’ Cadit quaestio. I shall endeavour to include this erudite contribution in the year exam paper: ‘Prospects for Marxism in the twenty-first century are pretty shabby, I suppose. Discuss.’”

It seemed that people got very emotional about this Marx guy. Melvyn Macveigh appeared to consider my disinterest unforgivably rude, as though Marx was in the room and I was refusing to pass him the cashew nuts. On one occasion, in Benny’s staff room, I overheard Lucy and Spocky discussing Marx as if he was an intimate friend who might at any moment arrive with their ice cream sundaes. What was the big deal?

At five o’clock, I was due to meet Lucy in the Student Union (she said she had “news”), which gave me three hours for research. In the University Library, I found the first book on Melvyn Macveigh’s reading list: Capital: Volume One. It was a bit slow to start with, certainly not a page-turner. I persevered but there was no discernible plot and there were too many formulae. This Marx guy was no John Grisham. Disillusioned, I put it back. What I needed was some perspective, a human angle; who was this guy? I returned to the catalogue and entered Marx as a title. This time it suggested Karl Marx: A Biography.

This was more like it. It turned out that Marx was a total chancer. Famous for theorising the emancipation of the working class, Marx spent all day drinking port at the expense of some Engels bloke who had inherited a factory. It seemed to me that Marx must have been sleeping with the Engels guy, because why else would Engels give him all that money? And get this: Marx had his bread buttered on both sides—he married Jenny von Westphalen, whose dad was a baron or something. One of the best bits in the book was when they could no longer afford their middleclass lifestyle and Marx sent his wife to scrounge off her parents. While she was away, he knocked up the servant.

At five o’clock, I explained all this to Lucy’s chest. Fortunately, Lucy didn’t notice that I spoke to her chest any more than she noticed that barmen always served her first, or that men walked backwards after they passed her in the street, or that women swore at their husbands and hissed “Marry her then!” as if she’d jump at the chance to bed down with their hairy-backed, baldheaded mates. “It’s quite a sad story,” I said. “All the children from his marriage died tragically.”

“Yeah, I heard that.”

“You wouldn’t believe it: Jennychen got cancer and died just before her dad. Laura Marx, she went and married this Paul Lafargue guy and they committed suicide together in 1911. The wee boy Edgar died of tuberculosis when he was just eight. Another two died as babies, a third before it could even be named, and get this: Eleanor Marx, she shacked up with this Edward Aveling guy—”

“Is this the suicide pact that wasn’t a suicide pact?”

“Aye,” I said, a bit pissed off to have my story spoiled. “I guess brains aren’t genetic. I mean, surely it’s the first rule of suicide pacts: if he hands you the prussic acid and insists you go first, don’t do it.”

Lucy laughed, lips red from the blackcurrant cordial in her snakebite. “Do you know about Marx’s bastard child? Not Lenin, I mean the one he had with the servant?” Lucy was originally from the North West and she spoke with a Gaelic lull that sort of lingered, so that my replies always seemed delayed, as if we were talking on a satellite link.

“Aye, I read that too.”

“How is the arm?” she asked, her expression changing as she watched me struggle to get a fag out with one hand.

“Alright. I’m supposed to get the stitches out tomorrow.”

She shook her head and touched my knee as three students cheered, The Simpsons tune jingled, lights fizzed and sparked, and coins rattled out of a fruit machine.