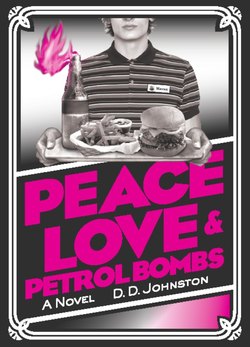

Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление4

The stabbing? Okay.

A canal runs through Dundule. There’s no lighting—not many people would choose to walk there on a November night—but in 1998, I always went home that way. I liked its cavernous stone cul-de-sacs and the rusty rings on its overgrown mooring plinths. I used to think, what an effort, what labour, to have built all this only for it to be replaced by the railway. It runs for eight miles, and then it just stops.

Under the bridge, where the road passes overhead, I heard shouting and laughing and saw three boys—fourteen year olds? Fifteen year olds? They were arranged in order of height, swaggering to fill the track. One of them whispered, “That’s that cunt that jumps aboot wi that Jason radge.”

“Fuckin bawbag!”

I kept walking, pretending I couldn’t hear them.

“Here, cunto! Dickheid, we’re talkin tae you.” In the distance there were fireworks, shot up a mile or two away, bursting red, amber, and green. I turned, just as the middle-sized guy shoved me. Then I was stumbling backwards and he was following me, fists clenched, shouting “You mind Giorgio, eh? You mind Giorgio, eh? Ya fuckin radge cunt.” He was leaning into my face and shouting and I could feel his breath. And the world bleached white because when I lose my temper I get this—it’s not a red mist, it’s more like white dots that merge together until I can’t see, like a blizzard that gets faster and faster until—

The only thing I can tell you is that I would have expected more pain. At first I thought someone had punched me. Then my whole side was warm and I saw the blood running oily thick from my fist and the kids saw the blood and for a moment we all stood there and stared. Then they ran towards the road and I remember being on my haunches, jeans soaking up puddle water. Then I stood up, dizzy and sick, alone but conscious of how this looked—the blood, the fireworks, the whole composition of the scene. I wrapped my jumper around the wound and stumbled towards the street lights.

On the main road, the taxi drivers swerved towards me, saw the blood, and accelerated. I had to jump in front of a black cab, place my hands on the bonnet. “Please, I really need to get to hospital?”

At A&E, the receptionist took my details. A mop diluted my blood on the plastic floor. They slammed me on a trolley and crashed me through swinging doors. “Okay, he’s nineteen, lacerations on the upper arm.”

They wanted to know what had happened.

But how far back do you go? Should I start with the blowjob in the Railway Inn? With Deanne? With her butterfly tattoo, short skirts, and ripped stockings? Jerry the Fence’s daughter, Gordon’s cousin, and briefly, briefly, my girlfriend, Deanne was eighteen when eighteen was impossibly old. When I met her in the summer of ’96, Deanne was already old enough to work in a bar. She was old enough to know how to slam tequila with salt and lemon. She was old enough to have a stud in her tongue.

When Gordon introduced us, we were drinking illegally in his uncle’s pub. Joop perfume buzzed around Deanne like an entourage. She had big lips and acne and a brown face that shared a neat border with a white neck; she had big gold earrings, like coopers’ hoops, trussed in her platinum blonde hair.

When it was late and we were drunk, she followed me into the gents, shoved me into the cubicle, and grabbed the back of my head, crashing our teeth. She kissed a sloppy wet kiss with a slimy wet tongue—she kissed like a Labrador—and then she unbuckled my belt. Imagine it: I’ve spent the whole night trying to hide my erection, but just when I need it, my cock’s wrinkled and small. She takes it in her mouth (kneeling on the pissy wet tiles, heels pressed against the foot of the door), and pulls her skirt to her waist, but all I can think about is the hole in the door where a lock might have been, the toilet seat propped on the barred windowsill, the gang names carved into the ceiling, the charred bog roll holder, the bloody bogeys smeared on the partition. On the other side of the door, some guy’s piss is thundering into the tin urinal. He farts and exhales in satisfaction. I can’t do this!

She stops. “What’s wrong?” she whispers, holding my dick in her hand.

“Nothing.”

“Nothin?” She throws the flaccid penis at me in disgust.

“...”

“Are you queer or somethin?”

“No! Fuck no.”

“Do you no fancy me?”

“Oh aye, totally, you’re well tidy.”

“Can you no get stiffies?”

“Aye, course I can. It’s just…”

“What?”

“Well, I’m a wee bit nervous.”

“What the fuck have ye got tae be nervous aboot?”

“Just cause, cause… I’ve no really done it before?”

She laughs and laughs and laughs.

Or, if I start by describing the Southfield Fry, its own story will be left hanging. Why did Grandpa Salvatori leave Parma to sell deepfried food in a Scottish housing scheme? Whatever the reasons, the Southfield Fry was probably the best chip shop in the world. Even to open the door felt like you were releasing a genie: all the pent up steam would push past you and soar, liberated in the cold air.

After swimming, we’d warm our paws on the hot cabinet, and Gianfranco would yell “Dinnae put yer honds on the cabinet, ye mucky wee bastards.” We’d pull our pink wrinkled fingers from the glass and press them on the stainless steel and watch as our fuzzy prints faded then disappeared.

Gianfranco’s menu, a yellowing fat-speckled piece of card, was as limited as his customer service skills. You could have chips, chip butty, fish, sausage, haggis, or pie. In 1993, he introduced deepfried pizzas, but these were never added to the grease-stained menu, nor were the cigarettes and chocolate bars, or the big glass bottles of Irn Bru and ginger beer. These sat on shelves behind the counter, wearing their prices on star-shaped orange badges. In 1996, the only other decoration was a fixtures chart from the 1986 world cup, a picture of Rossi, and a framed photograph of a Parma side from the seventies. The Southfield Fry was only two and a half metres wide by six metres long. There were no seats and no “chip-forks”; you bought your food, you fucked off outside, and you got your hands greasy.

In short, but for the Salvatori family’s legendary frying skills, there would have been no reason to patronise the place; and if you frequented Salvatori’s in the mid-nineties, chances are you would have heard Gianfranco lament his son’s refusal to fry. “The boy can dae it, ken? He jist wilnae. And it’s no suttin you can teach any doss cunt; it’s in here,” he’d say, beating his chest. But though he was about as Italian as the food his father served, Giorgio Salvatori had reinvented himself as a Sicilian entrepreneur. He had the name, the dark eyes and Mediterranean features; it was nothing to affect a thick Italian-American accent. In 1996, he was nineteen and had started to traffic fake or stolen designer clothes. As an aspiring Mafioso, he had acquired a Vauxhall Astra, a fake Rolex, and one of the biggest gold chains in Dundule.

And then he met Deanne.

I won’t pretend that I wasn’t upset when she dumped me in favour of Giorgio, but I certainly wasn’t bitter. He was older and better looking than I was. He had a car and a fake Rolex. For her to have done anything else would have been a sign that she was crazy.

The day I chose to say goodbye was the warmest of the year. On Deanne’s street, an ice-cream van Popeye jingle drifted from two blocks away. A boy practised wheelies. On a small square of grass, a bare-chested man putted golf balls, while a wasp crawled round and round on his beer can, tilting its bottom up before disappearing inside. Between cars, three girls in football shirts clapped and swung a rope:

“Ah wet ma hole, wet ma hole, wet ma holidays,

Tae see the cunt, tae see the cunt, tae see the cuntary.

Fuck you! Fuck you! Fu-curiosity,

Ah wet ma hole, wet ma hole, wet ma holidays.”

And a girl on a plastic tricycle, mouth sticky and purple from ice poles, pedalled the pavement, singing “Wet mole, wet mole, wet moley say, you a cunt, you a cunt, you dee-dee-da-day.”

Deanne’s gate was rusty and it scratched a curved groove on the first slab of the concrete path. The grass was long and yellow and trance music bounced through an open window. She answered the door in her dressing gown. “Wayne, what the fuck are you doin here?”

“Well, thing is see, I know you’re seeing Giorgio and that but—”

“Wayne, ah telt ye before: it’s over between us.”

“Aye, I ken, but—”

“No buts, Wayne. Over. Finished. Goodbye.”

“I’m no trying to get back with you, I just wanted—”

“You shouldnae be comin roond like this. Come on, clear off.”

“No until I get a chance to talk with you.”

“Wayne? Do yersel a favour—” There were thuds on the stairs. A pair of Lacoste shoes. New Levis. A fake Rolex. A Henri Lloyd polo shirt. A big gold chain. “Whadda fuck are you doin here, ah?”

“Alright Giorgio.”

“Alright? Am I alright? Look in my eyes. Are these the eyes of a man who is alright?”

“I’m only here to get my CD back.”

“You came for a CD? What fuckin CD?”

“Bonkers.”

“Did I fuckin ask you? Bonkers, where’s that? Is that in your room?” He bounded back up the stairs.

“Wayne,” whispered Deanne, stroking my cheek, “dinnae come roond again.”

The girls had stopped skipping and were leaning on the fence. “Are yous gonnae start swedgin?”

“Giorgio will kick yer heid in.”

“Fuck off and play,” said Deanne.

“This fuckin CD?” Giorgio ran down the stairs and threw the box onto the concrete path. It bounced and landed in the long grass, so he ran up the path and stamped on it. Then he dragged the disk out, holding it flashing in the sun. “This fuckin CD?” He tried to snap it.

“Dinnae!”

It buckled but wouldn’t break, so he frisbeed it into the street. As I turned to watch its flight, Giorgio kicked me hard up the arse.

Jerry the Fence’s shop, below the tenements, at the far end of Lanark Road, with the sign promising “Cash paid for jewellery, antiques, scrap gold and other valuables,” and the dusty windows, and the wire mesh, was the sort of place where you thought seriously before you entered, where you studied the chain you wanted while mustering your courage, where you stood at the door, breathed deeply, and pushed.

The day after my altercation with Giorgio, I found Jerry berating a customer. “I dinnae gie a fuck what yer mother paid for it. That’s nine-carat gold and cubic fuckin zirconia. If yer mother bought that thinkin they were diamonds then she was as stupid as you are.”

“Well at Cash Creator…”

“Cash Creator! Those fuckin bandits, they wouldnae pay ye a price even if they were fuckin diamonds. You could walk in there with Tutankhamun’s Tomb and the bastards would offer ye twenty quid: ‘Well knowin the second hand business like I do, there’s no much demand for Tutankhamun’s tomb.’ Offer the bastards a Fabergé egg and they’ll tell ye it’s worth a fiver and they’ve already got three up the stair!” The man shrugged and gathered his things. Jerry watched him stoop over the counter. “Yer rabbit there. Quite a nice piece.”

“Aye ?”

“Aye. How did ye get hold of this? Royal Worcester Porcelain. Dates fae about the time of the First World War, that. They didnae make many of these brown ones. Quite a nice piece… I might be able to sell yer rabbit, and I suppose I could take the rest off yer hands as a favour. Say,” he exhaled, “eighty quid?”

The man shrugged again. “Aye,” he said, but with his eyes closed.

“Right, let me nip tae ma safe.” The man lay the ring in his palm, tracing its circumference with a dirty finger. Jerry returned with a grin and started to count. “Twenty, forty, sixty.” You could hear the notes whispering between his fingers. “And that’s eighty. Pleasure doin business with you.” The man shuffled past me; he stank of piss and booze. “Wayne,” said Jerry, “how are you?”

“No bad, Jerry.”

“Aye,” he said, showing those yellow teeth. “Come through, come through.” He pressed a button and the wire gate pushed open. “Gordon’s in the back. Let Uncle Jerry put these things away and I’ll be through for a spraff. Tell Gordon tae put the kettle on.”

No matter how short Gordon cropped his hair, you could still tell he was ginger. That summer he was supposed to be learning the retail trade from Jerry, but I found him slouched in an armchair, trying to ignore Jason. Jason was kneeling on a large square cushion, punching it. He pulled a corner to his contorted face and head-butted it. “Stitch: like fuckin that.” It was a demonstration of what he’d done to someone, or what he was going to do to someone, or what he would do if he ever met someone—if, just supposing, those fucking Gallagher twats came in here trying to act hard, giving it, “Alright ahr kid, let’s fuckin ave it,” then Jason would be like, “Right you English cunts,” and he’d leather them, get on top of Liam and smack his nose so it went back into his brain. Stitch: like fucking that. He stopped and looked at me. “Fuck are you lookin at?”

“Alright Jason.”

“Naw. Ah’m fuckin no.”

“Jerry says you’re tae put the kettle on, by the way.”

“Dinnae fuckin ignore me, ya tube.”

Gordon shuffled to the kettle.

“You’re a fuckin wide-o, by the way, goin aboot sayin ye can have me and aw this.”

“...”

Jason ran across the floor and bored his forehead into mine. “Fuck are ye smilin at?” We stood head to head and you could hear his leather jacket creak.

“Anybody else wantin tea?” asked Gordon.

“Aye, ah’ll take one. Fuck sake, Wayne. Nae need tae get aw humpty; ah wis only huvin a laugh wi ye.”

As I smiled and tried to laugh, Gordon opened the door to the toilet cubicle and a cloud of smell floated across the back room—a stench of shit that wore lemon air freshener like earrings. “What’s that stink?” said Jason. “Were ye that feart ye shat yer keks, Wayne?” Jerry had permanent diarrhoea, something to do with the drugs he took for his HIV, and sometimes we’d hear rasping, splattering excretions, that were violent and thrashing like a fight in a swimming pool.

Gordon turned the tap. The pipes groaned and the trickle clattered the metal wash basin. “You huvin tea, Wayne?”

“Nah, no thanks,” I said, sitting on Jerry’s footstool.

Jason crossed the room to spit in the sink. He dredged for more phlegm, spat again, dredged again. He was always dredging for phlegm and spitting clear saliva. It was like someone had put something horrible inside him and he couldn’t get it out. After a minute, he slumped into the armchair and rested his feet on my lap. I shook them off. “Dick,” he said, kicking my shin, but he didn’t put his feet back. “No danger ah’m sittin aboot here aw day, by the way.”

The backroom was a grim place to spend a sunny afternoon: it had one small barred window and a bare light bulb and cracks crawled across the dark corners of its ceiling. The shelves were cluttered with broken electrics and equipment for examining or repairing jewellery. There were a few books and some yellowing copies of the Daily Mail. We had long ago decided that all the excitement happened in Jerry’s office, where we weren’t allowed. In Jerry’s office, deals were concluded with international art thieves, or so we liked to think.

“Is that kettle boiled?” called Jerry (Jason jumped out of the armchair). “Ahhh, there we go. Aye.” Jerry sat down, sighing in chorus with the chair. “So Wayne, have you and Deanne patched things up yet?” He noticed something in the Daily Mail and lost interest in his own question.

“Aye and no. No and aye. I seen her, but just to get my Bonkers CD. You ken how it is; we’ve just grown apart. We’ll definitely stay friends.”

“Aye” said Jerry. “I told her, Wayne. I said no lass of mine’s gonnae marry a wop. You know? I said the bastard will change sides in the time it takes ye tae walk up the aisle. Abscond wi the minister or something.”

“Did you get it?” asked Gordon.

“What?”

“The CD.”

“Aye, well. No. He broke it.”

“I told her, an Eyetie’s only a bit better than a nigger.”

“Who?”

“Fuckin Giorgio.”

“Fenian bastard,” said Jason.

“How?” said Gordon.

“Well, I was talking to Deanne and he was hanging about like a bad smell. So I was like, ‘Look mate, make yourself useful: nip upstairs and get my CD.’ When he brings it down, it’s broken. So I’m like, ‘What the fuck’s with this?’ He’s all like, ‘Oh I don’t know anything about it.’ And I’m just like, ‘You’re fuckin sad mate.’ Then he starts going radio, so I’m like, ‘Let’s fucking go.’ And he slams the door, bolts it, and starts shouting through the letterbox that he’s gonnae get a posse to kick my head in.”

“Aye?” said Gordon, not totally convinced by this version of events.

“That’s oot ae order,” said Jason. “That prick thinks he runs this toon.”

“And he’s been treatin Deanne like shite. I’ve heard he’s goin aboot callin her a whore and that.”

“Fuckin Brussels,” said Jerry, shaking his head at the paper.

I remember us on Giorgio’s street: three long shadows like something from a western. I remember us at his door. Gordon and Jason are hiding against the wall. Gordon is patting a pudgy palm with a knuckle of medallion rings, and Jason is holding a hammer. I chap the letterbox. “Dae it fuckin properly,” says Jason. He spits on the path and rattles the flap as hard as he can.

An internal door opens. A television audience applauds. The lock clunks. Giorgio stands in a white Yves Saint Laurent shirt. “Whadda fuck? Whad’I fuckin tell you, ah?” Jason leaps from behind the door and cracks Giorgio’s thigh with the hammer. He thumps the hammer into his ribs—like he’s chopping a tree. Giorgio falls into the hallway and Jason jumps on him, punching his face, again and again. Giorgio’s head is whiplashing, bouncing off the ground, and Deanne’s running down the stairs with her nightgown open.