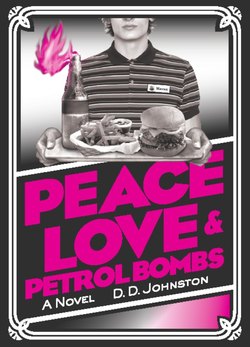

Читать книгу Peace, Love & Petrol Bombs - D. D. Johnston - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление6

“What d’you make of that new guy? I think he’s mental.”

“Who?” said Buzz. “That Doddy guy?”

“The cunt wi the stutter?” asked Gordon.

“Nah, no him. That guy with the glasses.”

“...”

“...”

“He started about a month ago. The fucking Star Trek guy.”

“Oh, that cunt,” said Gordon.

“That guy’s funny,” said Buzz.

“Funny? He’s fucking lazy.”

“He takes no shit.”

“Ever since he’s started, I’ve kept finding him hiding in The Cave.”

“It’s always the same mugs dae aw the work,” said Gordon, shaking his head.

We were in the Railway Arms, Jerry the Fence’s pub, where two years earlier, Gordon had introduced me to Deanne. The Railway was a dingy bar with long burgundy curtains and nicotine-stained walls. The leather upholstery on the wooden benches was tough and cracked like the surface of cricket balls. The air was always so thick with smoke and dust that you imagined you were exploring a new planet, whose alien atmosphere might not support life. Guarding a half of cider in the lounge area, a bag lady attempted to initiate conversations with real and imagined passers by. Alcoholic Tam crashed between tables, singing “What a Wonderful World.” And an old man hunched over a horse racing paper, his pipe unlit as his half of eighty evaporated. The only other customer, a stocky Teddy Boy, stood fumbling and cursing at the jukebox. “Whose round is it?” I asked.

“It’s true,” said Buzz. “We do that much work and get no reward. Like, remember that all-night close last week? Man, we were there till when? Like, ten o’clock the next morning. What did they promise us? Twenty quid each, yeah? Check your pay slips. Seriously guys, it’s not there.” Buzz’s glasses were held together with Sellotape and his jumper belonged to someone older and fatter; even by the standards of the Railway Arms, even next to a bag lady obese with layers of clothes, Buzz managed to look noticeably unkempt.

“I got the last one,” I said.

“Well, fuckin, yous both owe me drinks,” said Gordon.

“And it keeps happening. D’you remember the extra shifts when Andy Duke came from head office?”

“Oh aye, fifteen bar I shouldae got for that.”

“It’s your round, Buzz.”

“Damnit man,” he said, kicking back his stool.

The setting sun poked through the windows, illuminating the swirling clouds of smoke and dust, spearing a shaft of light towards the old pipe smoker. I never saw anyone die in the Railway Arms, but that being remarkable tells you it wasn’t the sort of place where you went to pick up girls or have fun. “There’s other places for that sort of thing,” Deborah, the bartender, used to say if anyone sang or fought or danced or kissed.

As she poured our drinks, the old Teddy Boy touched me on the shoulder with fingers that had swollen around gold signet rings. “Gie me a hand wi this, son.” Maybe he’d had a stroke at some time because one quarter of his pockmarked face was frozen, with the corner of his mouth held down in a way that made you think of a sad clown. “I’m a bit shaky, shaky,” he said, pushing fifty pence into my hand. “Elvis, son. Elvis and one for yersel.” I selected the Elvis CD and invited him to pick, but he looked tired from standing and sat down beside the jukebox. “Anything son. Anything by Elvis.” I was unsure what to play but I chose “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock,” and I chose “Tubthumping” for myself. The Teddy Boy closed his eyes, tapped his foot, and hummed.

Meanwhile, Buzz lowered a triangle of pints and slapped on the table four pound notes, eighty-six pence, and a sweaty bus ticket. “Guys, it’s six o’clock on payday, and in a few hours I’m going to be skint.”

“We should huv a union,” said Gordon, and we all laughed.

“You know that Doddy with the stutter? New guy, been trained on chicken?”

“Oh aye.”

“He was saying that he used to work on this building site where they had a union.”

“Oh fuck,” I said, “he told me the same story. It takes the guy fifteen minutes to tell you his name. ‘We had a you-you-you, a you-you-you, a youn—a youn—’ It’s embarrassing; you dinnae ken whether to finish his sentences or what.”

Gordon laughed. “And?”

“Well,” said Buzz, “that was it, really. They had a health and safety officer and got paid five-fifty an hour with time-and-a-half for overtime.”

“Cause of the union?”

“So he reckons.”

“Nah, see, the question I asked him was this: if the job was so great, how come he’s not still working there?” Gordon nodded at the salience of this inquiry. “And he says, ‘Cause I got sacked.’ So I asks, ‘What did the union do about that?’ ‘Nothing,’ he says. So what happened to all the money he paid in, eh? I’ll tell you what: they spent it on a plush conference and a campaign about lesbians in the construction industry.” There was nothing more to say on that topic so we sat and sipped our pints.

“Magic,” said the Teddy Boy. “The King—fuckin magic.”

He died later that year, the Teddy Boy, in our work. He was waiting to buy his burger and the service was so slow that he died before he ever had a chance to order. You saw the queue step away from him as he clutched the counter with those fat fingers, and then, almost with a look of release, like someone who has heard the punch line to a long joke, he timbered, falling so big and heavy that other customers moved out of his way. You expected him to cry out when he hit the floor, but the only noise was the beep beep—beep beep—beep beep of the fry timers. Then, as if she’d been waiting for this, LeAnn Rimes started to sing.

You almost expected more from a dead person, like you wanted him to do more than just lie there. I mean, if he was going to die then you wanted it to have some weight—to be less... silly.

“Fuck,” said Raj, kneeling beside the body. “Come on, stand back. Ah bollocks. Can you hear me mate? Mate? Phone a fuckin ambulance!”

“Take his pulse,” said a man in the queue.

“Just gies a bit of space, please. Mate? Hello sir, can you hear me?”

“He can’t hear you,” said the man in the queue.

Kit appeared from the office, with the phone cord stretching taut from her neck. “Is he breathing?” she asked.

Raj put his ear to the Teddy Boy’s chest. “Dinnae think so.”

“Oh dear,” said the man in the queue.

“Here, put this under his heid,” said an old lady, offering her coat.

“Has he got a pulse?” shouted Kit.

“Yes,” said Raj. “No. I Dinnae ken. I cannae find it!”

“He’s dead,” said the man in the queue.

“He’s no dead,” said Raj, wedging the coat beneath the Teddy Boy’s head.

“How auld is he?” shouted Kit.

“How the fuck would I ken? Fuck man. Have we got a doctor? Any doctors in the house?” But you find doctors in concert halls, on international flights, and onboard cruise ships, not in burger bars in small Scottish towns. “Ah fuck,” said Raj. “Okay. Alright. Here we go.”

“Give him the kiss of life,” said the man in the queue.

“Would you shut the fuck up? Here we go. Come on. Wake up, damnit.” He pounded the Teddy Boy’s chest with both hands and forced air into his lungs (if the heart attack hadn’t killed him then that would have finished him off), and as time passed, and the man in the queue looked increasingly satisfied, Raj pushed the Teddy’s Boy’s chest harder and harder, until the noise it made was like someone beating a dusty carpet with a stick. When the spectacle became grotesque, Gordon draped his arm on Raj’s shoulders, the way nurses comfort doctors when a patient dies on ER, and he said, “Raj man, we’ve lost him. Ye’ve done aw ye can.” Raj stood up, maybe a little watery in the eyes, and the Teddy Boy stayed where he had fallen. “Mate, there was nuttin ye could dae.”

“Bhenchod, I couldnae mind the course.”

“It wasnae yer fault. Fuck, you’d’ve had mair chance tryin tae resuscitate one of our quarter pounders.” Gordon pulled the coat from under the Teddy Boy’s head and draped it over the body (the old lady crossed herself and looked at her coat, as though wondering when it would be appropriate to ask for it back). “Alright,” announced Kieran. “Come on now. Let’s see a bit of service, yeah?”

It’s difficult to say why the death affected us; the customers straightened themselves and shuffled forward, gaping at the menu as they readied their cash, but some unknown glitch prevented us from taking their orders. “We need more fries down,” said Kieran, because the ones in the baskets, neglected during the resuscitation attempt, had turned hard and brown. “Ps and Qs, yeah? People, procedures, profitability. Quick, quality, quantity.”

“...”

“Guys? Come on. Let’s do this, yeah?”

Kit looked at me and I looked at Gordon and Gordon looked at Lucy and nobody moved. “Dude, this isn’t cool,” said Buzz.

“Alright, no more Mr. Nice Guy, yeah? Work. Now.”

“No,” said Kit.

“Work.”

“Nu.”

“Work or you’re sacked.”

“All of us?” asked Buzz.

That was when the new guy spoke up. As usual, Spocky was out in the dining area (the only place where he didn’t compromise the whole shift), where he should have been wiping tables or sweeping the floor. Instead, he walked up to the Teddy Boy’s corpse. “Hey, can someone give me a hand? Let’s get this body into the freezer.” The customers looked at him, unsure if he was for real, while Kieran gestured for him to shut up. “I’m serious. Come on, we can’t leave him here.”

“Okay, fine. You know what? For that, you’re on a final warning.”

“Think about the food costs. We can get three boxes of meat out of this guy.”

“Okay, done. Finished. You just talked yourself out of a job.”

Then Buzz sheathed his grill spatula and shouted from the kitchen. “If he’s out of a job, so are the rest of us.”

“Aye, fuck this,” said Gordon.

Kieran strained his muscles in a disorientated attempt to smile. “What is this, a strike?” And in the silence that followed, at more or less the same time, Kieran realised, and we realised—aye, it was.

And what a feeling it is to have your time unexpectedly reimbursed. It was like when the school heating broke or the pipes burst or the teachers went on strike. We paused on our way to the Railway because through the window, beneath an advertisement for “Buy one get one free” chicken burgers, we could see Kieran stocking the condiment trays as the paramedics shocked the Teddy Boy’s corpse. When they gave up and loaded him onto a stretcher, Kieran mopped the tiles and marked the spot with a “Caution! Wet Floor” sign.

“D’you think we’re gonnae get in shit for this?” asked Kit, pressing up to me for warmth. She picked up the smell of grease like the rest of us but there was a space at her nape, especially when she wore her hair down, where you could sniff out a lemony shampoo smell.

“Probably,” I said.

“Aw man,” said Buzz.

Gordon shrugged. “If we aw stick together then they cannae touch us.”

A few metres from us, Spocky stood alone, trying to form a shelter in which to roll a cigarette. In the border, between the knee-high shrubs, the wind was swirling litter and strips of bark. This eddy of woodchip and rubbish invaded Spocky’s shelter, flapping his Rizzla and scattering his tobacco. “Hey,” shouted Lucy, “Do you want one of these?” Her hair whipped around her face as she held out a cigarette.

Spocky looked a bit suspicious, but he shuffled forward and took the fag. “Okay, thanks.”

“It’s Owen, isn’t it?”

“Yeah, Owen.”

“Some of us are going for a drink, if you fancy it?”

“I don’t really drink.”

“Well, have a coffee or something?”

He looked at his watch. “Okay, yeah. Alright.”

Now, as you can probably guess, the Railway Arms was not the sort of bar that served coffee. There was no family area or smoke-free zone, traditional bar meals were not served all day, and there was no wine list. There was a quiz night every Monday, and it was the sort of quiz where all the rounds were about horse racing or the filmography of Clint Eastwood, where any question about the periodic table or South American geography was met with cries of, “It’s no University Challenge!” and, “Come on, Paxman, this is a working man’s pub.”

However, Spocky didn’t know this. Spocky joined us, and this slight deviation, this jolt, would veer us into the future, reminding us that stories can be retold, that we don’t always have to follow the tracks, that sometimes people like Owen can make a difference.

“Jerry? Gordon’s here,” called Deborah as we entered the bar. “Drinking in the afternoon again, Gordon? Hi Wayne. Jesus, who’s died?”

“One of our customers,” said Lucy.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” said Deborah. “I thought yous were looking glum.”

“He used tae drink in here sometimes,” said Gordon.

“Oh, really? Here, Jerry, listen to this—one of the punters has passed on.”

“Oh aye, who’s that then?” asked Jerry without looking up from his paperwork.

“Old bloke,” I said. “Big guy. Lot of gold rings.”

“What was he called?” asked Deborah.

“Dinnae ken,” said Gordon.

“He had a frozen face, kind of like—” Buzz girned an impersonation of the Teddy Boy’s paralysed face.

“Who would that be, Jerry?”

Jerry peered over his half moons. “Naebody ah ken; looks like the Queen Mum.”

“His face was kind of pockmarked,” said Kit.

Deborah shook her head.

“He liked Elvis,” I said.

“You sure he drank in here?” asked Deborah.

A man with a big moustache, who’d been listening to the conversation from his seat at the end of the bar, now put down his newspaper. “Sure, that’s yer man. What did ye call him—Jesus, hang on. He had a tattoo of Elvis, so he did. Gary… Gary Thompson his name was.”

“Oh aye,” said the old man with the pipe, “he’s always playing that bloody jukebox. The boy’s a pain in the arse. What aboot him, anyway?”

“He’s passed on,” said the guy with the moustache.

“No he hasnae.”

“According to these young ones he has.”

“Havers—he was here not forty-five minutes ago.”

“Aye,” said Gordon, “then he went across the road and died.”

“Well, fancy that. It’s this wind, I tell you; it’s the Devil,” said Deborah. “I ken who you mean now. Gary… Are you sure his name was Gary?”

The old man looked sceptical. “Across the road where?”

“That burger shop,” said Deborah.

“Ach no. That’s no place tae die.”

Deborah shook her head. “Well, it just goes to show, doesn’t it?” She smiled at Lucy. “What can I get you love?”