Читать книгу The Handcarved Bowl - Danielle Rose Byrd - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление10

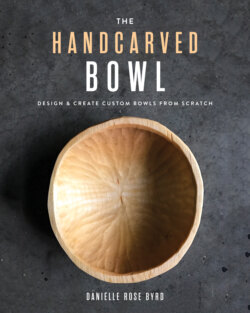

T H E H A N D C A R V E D B O W L

INTRODUCTION

W

oodworking appeals to so many people because it

gives us the opportunity to work with our hands to

make something tangible, and maybe even useful, too.

Or perhaps it’s to feel a connection to something after

working a job that isn’t all that fulfilling, or to help

ease anxiety, or get outside. Bending, shaping, carving,

and cutting are more than just steps to create an ob-

ject, but I suspect most of you know this already. Sure,

this book is a guide to bowl carving, but I hope that it

also serves as a reminder to enjoy the process, even

when we feel like we’re failing, and especially when we

feel like we’re failing.

Working green wood is an inherently risky process,

and the number of things that could go wrong is,

frankly, overwhelming. The material itself demands

a good deal of consideration and respect, and

sometimes even when we grant it every forethought

we can muster, it will still find a way to humble

our incessant desire for certainty. And I find this

absolutely exhilarating! Many of my best designs have

been born from what I originally deemed failures,

so I’ve learned to treat my response to them as yet

another skill to hone.

The beauty of this process is that it also presents us

with the opportunity to make mistakes deliberately,

ones we can feel with our hands, and see with our eyes,

and better learn how to remedy. With so many other

abstract and complex problems in our world, witness-

ing the unfolding right in our hands, and because

of our hands, gives us the ability to see exactly what

needs to be done to fix it. Our drive to become better

with our tools, I would argue, is not to make a prettier

bowl or a smoother surface, but to chase the certainty

we seek in other arenas—the things we couldn’t possi-

bly fix in one carving session.

In recent years, green woodworking has taken off,

and it’s no surprise why—it requires little overhead

in the way of tools, space, and materials, at least

compared to machine woodworking, and projects

can usually be completed in a fraction of the time it

would take to fully realize a piece of fine furniture. The

high moisture content of green wood makes it easily

workable compared to dried wood, and a downright

pleasure to work with hand tools. At one point or

another, a good deal of us have had the experience

of using a simple pocketknife to make a mere stick

into a deadly spear. And what a spear it was! It’s likely

most of us were having our first encounter with green

woodworking without even knowing it.

My own journey into this field began in western

Maine, where shop class was still a thing back in the

90s. Though few have survived since, trade programs

like this were originally influenced by the Russian

system, and brought into American schools at the

turn of the 20th century to quickly equip students for

industrial jobs. This way of teaching focused more on

production, and not the development of the student in

both mind and body.

The sloyd system was brought over to the U.S. from

Sweden at around the same time, and caught on

in pockets, specifically at the North Bennet Street

School in Boston. The sloyd focus was on the student

as a whole—mental, physical, and moral—while also

creating things of use. It introduced young children

to hand skills with sharp tools starting at a young

age, which was looked down upon. Meanwhile, the

American Dream took hold, along with the teaching

methods that churned out workers to produce goods

and feed the dream, and the sloyd system fell to

the wayside.