Читать книгу The Handcarved Bowl - Danielle Rose Byrd - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление8

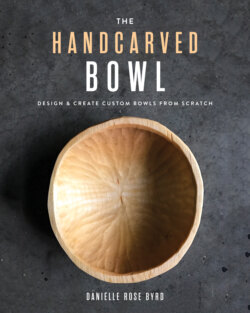

T H E H A N D C A R V E D B O W L

FOREWORD

BY PETER GALBERT

“What does education often do? It makes a straight-cut ditch of a free, meandering brook.”

Henry David Thoreau

T

horeau’s statement lives rent free in my head. As

both as a craftsman and a teacher, I know learning

is a risky venture and everyone does it differently. It’s

a tall order to inform, inspire, and enable someone to

achieve something new. Anyone who has ever taught

a dog knows that moment when they look to you

nervous, unsure, eager to understand. I know that look

well, from both dogs and people.

Most of my own woodworking education happens

somewhere between an open book and a pile of

shavings. It can be as frustrating as it is enlightening.

What is so special about this book is the attention

Danielle pays to the experience and expectations of

the reader. Her awareness of where uncertainty lurks

while students are learning is pitch perfect. There is

so much risk, beyond hitting your knee with an axe,

that a simple solution would be to regiment all the

instruction and just show the “correct” result: cut the

ditch straight and move on. But Danielle is wiser and

more capable than that. She will embolden you to

actually make a bowl, with all the effort and lessons it

entails, and to love learning the process along the way.

But I think she is more subversive than that; she

isn’t just showing you how to make a bowl, she’s

teaching you to learn to make YOUR bowl. Perhaps

I need to explain.

I met Danielle years ago when she was in a class I

was teaching at Lie-Nielsen. Danielle stuck to the

back of the class, kept to herself and silently went

about making the perch stool. I was curious about

her demeanor, not knowing if she was quiet because

she was shy, too cool for school, or, like me, a very

private learner. Whatever the case, I had a dozen other

students to worry about and one less person clamoring

for help was fine by me. Later, I started to see her work

popping up online as she was feeling her way into bowl

carving. While it was great to see her enthusiasm, I

didn’t know where she would take it. Her pieces didn’t

show the usual adherence to traditional forms so it

was hard to recognize her path.

Then something happened. Not just that she started

to show real proficiency, as nearly everyone does with

some effort, but, more importantly, that her work had

become expressive, creative, playful, confident. I saw

something I rarely see, which is why I’ve collected

her work and often dedicate time to staring at it. She

made carving into an art. Danielle pushed through

the process, using it to her own ends, revealing a

much deeper conversation she’s been having with

the material and the tools. Her bowls are alive, full of

movement, like the animals in the cave paintings in

Lascaux, lit by a flickering fire. All of a sudden, I knew

what she was doing in my class. She was gathering for

this conversation, taking whatever would serve her

purpose. My job was to speak my two cents and get the

hell out of the way.

Ever since those cave paintings were made, people

have crafted objects, revealing themselves in the

process. It’s how we survive, how we make sense of our

world. The things we make tell a story; there is always

something expressed, it just creeps in. I still have my

first spoons; they are tragically ugly and barely useful.