Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

The Trembling Woman

ОглавлениеIn contrast to the encounter with Thomas, where we look on with a combination of horror and fascination, we are drawn unreservedly into the scene with the unfortunate woman caught “in the very act.” Almost too easily. We are awed by the courage of Jesus and moved by the compassion and sheer power of his gesture.

At the same time, as easily as we inhabit the scene, we are struck by its strangeness. Jesus the talker asked directly to speak and refusing to answer. Meeting act with act, he initiates us in a ritual event. And John intensifies this by depicting Jesus stooping down and rising up twice, and the hostile crowd at the end leaving “one by one” in the most orderly fashion, from the eldest to the youngest (8:9). All playing out in the teeth of violence.

Here is the hostility and self-righteousness of a lynch mob combined with the rightness of the Law carried out by duly constituted judges. And into this charged atmosphere falls the radical gesture. Silence against clamor, as private ritual confronts public order. Individual authority challenges social authority. Outrageous. For in contemporary terms this would be like discovering that a neighbor is a drug dealer, and when we want to run him out of town, Jesus asks us, “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone” (8:7).

The magnitude of the gesture is unavoidable. In this simple act of forgiveness Jesus holds a knife to the throat of the body politic. We are shaken and exhilarated not only by this challenge to the order of society but by the spectacle of the word “law,” imbued with a long tradition of common-sense meaning, utterly emptied by a single gesture. The thing named “law” now unnamed.

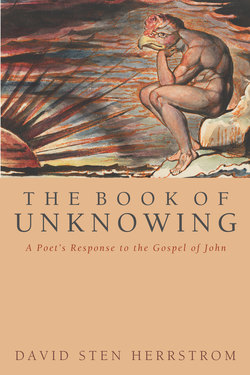

Jesus’ finger writing on the ground, William Blake the English poet and painter was correct in supposing, dares to erase the finger of God inscribing the Law on the tablet. No wonder Blake imagines that the “trembling Woman” can hear Jesus breathing as he stoops down, the very breath of God carrying her back to Eden before “Good & Evil.” Beyond the Law, beyond Good & Evil, Jesus’ act explodes meaning itself.

It’s as if the voluble preacher had come to the end of language, come to pure sign. Jesus is not speechless but pushes beyond speech. His act is radical both in returning us to an Eden before the split between good and evil, names and the things named, and in asserting human individuality now and for the future.

“Where are those thine accusers?” Jesus asks at the end of the scene (8:10). “Hath no man condemned thee?” These rhetorical questions reinforce our sense of emptiness, as if meaning were drained from the scene leaving only the compassionate act itself. Just the two of them left with the writing on the ground between them, which John cannily does not reveal to us, words being superceded, the body of accusers having been broken, each wandering off one by one lost in his individual conscience.