Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Beforehand

ОглавлениеWe’ve just finished eating dinner, and my father reads our daily chapter from the Bible. “In the beginning was the Word.” His voice gives the King James English a burr inherited from the “old country,” the Sweden of his youth. It seems as if every word is given its own knurl, the rough pattern of ridges that he puts on the knobs of the machine tools he spends his days making. Each word is accorded reverence and love. And at nine years old I knew this was how God himself pronounced them.

Compelled by some inchoate need as an adult to reacquaint myself, I revisited The Gospel According to John and gave a brief lecture for my colleagues where I was teaching English at the time. My talk wrestled with the beautiful shape and impossible demands of John’s Gospel. Circling it, awed and intimidated by his power, I finally saw an opening and got a hold. At last, I thought I had come to terms with his book. But like William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, it was too closely woven into the fabric of my life to let me rest.

So an encounter some thirty years later at the invitation of my brother-in-law, a minister, took me down, and I became obsessed with the book, reading and rereading. Nicodemus came by night in a dream. John sat beside me, conversing writer-to-writer in my daydreams. I avoided my colleagues at lunch, sneaking away to jot notes on the continual flow of my reader-reading thought.

•

My first encounter with John’s book as an adult was epitomized by the familiar medieval image of John the Apostle as an eagle, majestically soaring above us, distant, beautiful, essential. The eagle was the emblem of my awe. But my later encounter, which resulted in the present essay, is captured by the image of John as the rooster that haunts Peter.

As a boy I loved this engaging and intimidating scene of Peter’s denial. I identified with Peter, knowing in my heart of hearts that I too would have failed under the same circumstances. Still John loves him, treating him with a tenderness that even a boy could understand; and still Jesus loves him. Unspeakably comforting to a skinny kid filled with self doubt. And as an adult, encountering this scene almost thirty years ago and again recently, I still love Peter. But now I also love the interplay of John and Jesus, Peter and the girl and the soldiers around the fire, and the cock who crows. This time around it’s clear to me that John the writer, like the rooster in the scene, hovers just outside the action and, as the light of understanding dawns, sings for all he’s worth.

But we don’t have to choose between the eagle and the rooster. In John’s pushing the envelope of hope, he soars with the eagle; in testing the limits of the body, he crows with the cock. Swept away by a sublime life, lifted on currents of ineffable ecstasy, he views his hero from the heights like an eagle.

At the same time, he must contemplate the life. Eye witness or not, he observes Jesus closely in order to write his book. It is necessary to select and arrange events, include and cut speeches, comment on his hero’s words and actions. In short, telling the story of Jesus, as writer rather than follower, requires the distance that irony provides. In the close-up of wonder, every detail glows with equal importance. But to see clearly, the writer also needs perspective, the panning-shot of judgment that irony allows. Without it books cannot be made out of lives. So John’s Gospel, like the rooster’s song within it commenting on Peter’s actions, includes an ironic perspective.

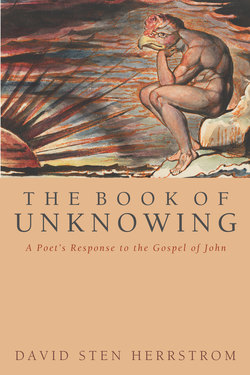

Throughout his book, then, John the follower and biographer of Jesus maintains a double vision. As a follower he desires to be Jesus; as a writer he seeks the distance that allows him to size Jesus up. His encounter with Jesus demands that he live in the center and observe from the periphery. Likewise, he invites us to give ourselves to certainty and embrace uncertainty, a recipe for the melancholy shared by all artists. On the title page to the triumphant last chapter of his epic poem Jerusalem, Blake portrayed just this conflicted, powerful creator-genius John, aptly drawing his head as both an eagle’s and a rooster’s. Here is the perfect emblem of John who is both the ecstatic follower and ironic writer.

•

Whether you come to John’s Gospel believing or suspending disbelief, his book has the power to transport. Whatever your conclusions about his hero, whether you are the follower worshipping him as God or the writer admiring him as an incandescent figure of inclusion and forgiveness, exclusion and judgment, John’s words sink to the depths of the soul. The awe-inspiring raptor and the mocking rooster haunt us all.

Because I have come to identify with John the writer struggling to make a book, I emphasize writer over follower in The Book of Unknowing. It is as writer that John struggles to turn into a gospel his encounter with the extraordinary person of Jesus, which he comes to experience as follower. Ultimately, however, one cannot be separated from the other, no more than how John makes his book—its sound and shape—can be separated from what his book is about. After all, a gospel is the “good news” that stays news not only because of the hero it celebrates but because of the way it is told.

In the telling, John does not proceed the way we’d expect from one who desires to tell the story of a life. Clearly, he cares more about eruptions of feeling and moments of revelation than about cause and consequence, the concerns of biographer or novelist. He gives us gestures that become emblematic, like Mary the sister of Lazarus pouring out the perfume and Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. He also gives us emotionally charged, natural objects that become symbolically revelatory, like bread and water. In this John is a poet. And I am caught up in the energy transferred across the divide of two millennia by these gestures and natural symbols. John’s anxieties and contrary emotional curves of certainty and uncertainty, the ways of metamorphosing his experience of Jesus into a lasting book of ecstasy and irony unsettle and exhilarate me.

I’m shaken by John’s yearning, disoriented by his pathos in face of losing what he most loves. Above all, I’m troubled and comforted by the book’s strangeness, which Sunday School and countless sermons cheated me of as a child. John’s mind, contrary to the soothing and smoothing teaching on Sunday morning, really does have rough, even intractable edges. It moves differently than ours, seizing on unlikely characters like Nicodemus, capturing a bewildering variety of moods in the voices of Jesus, or commenting on these from odd angles.

Beyond Sunday School, even sophisticated teaching has often cheated us of the peculiar orneriness and fragrance of John’s book. Much of the theological or devotional commentary on his Gospel simply translates it into another, more familiar language. Instead of looking the concrete, uncomfortable particulars in the eye, it turns away and takes refuge in abstract doctrinal or moral statements. But it’s the strange particulars that grab us by the throat and call our own lives into question. It is these very details I give myself to. Along the way, I answer basic questions that have nagged me for years: How does his book affect me? Why does it matter to me? On the other hand, I don’t mind raising questions which tend not to edification. Because I want not so much to convince as to create an appetite for John’s book.

•

Neither Biblical scholarship nor theological commentary, The Book of Unknowing is simply the personal record of one man’s reading some 2000 years later of John’s Gospel. A poetic talk on a poetic subject—John’s account of his encounter with Jesus—my book ranges the landscape of John’s language. This is a beautiful but often rocky country of sharp light, wild sounds, and sodden earthy smells.

And though it encompasses disparate places, from wedding hall to hillside, temple to shore; as well as people, from moneychangers to the woman taken in adultery, this country is one. It strikes us as the product of a unified if not single imagination. So we amble and clamber the book that has been received as a whole, rather than a layered composition, and whose impact has been felt as a whole by generations of worshippers. Although chapters 8 and 21, for example, were added at different times in the book’s making and almost certainly by different hands, the work received by English poets and believers as a unity is the locus of our exploration. And for this reason, I use mainly the Authorized Version, virtually the only gospel known up through the nineteenth century, and the one preferred by most writers into the last.

As a poet’s talk or lyrical “loose sally of the mind,” as Dr. Johnson defines “essay” (quoting Bacon), The Book of Unknowing attempts to be faithful to what John wrote while, at the same time, celebrating his words. I approach them receptively but also playfully. This is the way of Midrash, the revered body of Jewish interpretation, and the spirit of John himself as he interprets the ladder reaching to heaven in Jacob’s dream or of Jesus as he interprets the manna given to the Israelites in the desert. John not only invites interpretation by his own and his hero’s practice but by the gift to us of his doppelganger, a fellow interpreter who like all scholars loves the night hours.

And I accept this gift of Rabbi Nicodemus who appears in the beginning, middle, and end of the Gospel, a character through whose eyes John invites us to view his book. A Nicodemean reading is disinterested—respectful, curious, evaluative, observant—not dogmatic or subservient. Yet it is also empathetic and take’s John’s lead, following his own obsessions—image (light), symbol (water), sign (water to wine), shapeliness (symmetry), loves (Peter, the Mary’s), and above all words (the Word, the body, and the house of interpretation itself). Like all writers, John necessarily begins and ends in silence, but we see him in the middle distance probing the body—his own and Jesus’—deeper and deeper until he comes to its limit in the complexity of experience, which I call “unknowing.”

Like the Midrashim, I want to nurture his words so they will “enter and spread through the whole body,” as the words of the Torah were reputed to do. In this, too, I take John’s lead who wanted such experience for his readers, though he believed the outcome to be belief. Whatever relationship results, association is more important than ratiocination in this endeavor, so my book leaps more than it walks. It takes the furtive goat’s approach to John’s mountains rather than the methodical rock climber’s. I want to spark associations rather than argue a thesis (though the importance to John of the body and paradox is implicit), to be suggestive rather than exhaustive.

I ask more questions, following Nicodemus, than I answer. But the root of all my questions is this one: What would it be to write the book that John wrote? I read his book in this spirit, projecting his moves as a writer and after stumbling upon the steps he takes, asking about the ladder of argument or arc of associations that prompted them. Along the way, to help me with the how and why of John’s strategies, I call on other poets, such as William Blake and Emily Dickinson.

Not surprisingly, the result is a poet’s, rather than a preacher’s or theologian’s or scholar’s reading (though I’m grateful for Raymond E. Brown’s edition of John’s Gospel). I celebrate John the poet, pay homage to the look and feel of his book’s terrain, its snags and beautiful forms, rather than attempt to extract some pure, eternal ore that lies beneath. “Objections, digressions, gay mistrust, the delight in mockery are signs of health: everything unconditional belongs to pathology,” says one of Nietzsche’s aphorisms. The poet John agrees in his obsessions and artistic moves. And in the end I cannot separate artistic from spiritual power.

•

Ranging the country of John’s book, then, I describe the waves of language that spill over me and try to catch the ear-surprises of unknown tongues, measuring the pitch of these voices, which disturb and alienate even as they promise more life, like a seventeenth-century Mexican painting I recall. At once gruesome and tender, it depicted a grape vine growing from the wound in the side of Jesus, who is squeezing the juice from one of its luscious clusters into a chalice held by a kneeling priest. The worshipper looks heavenward into the face of Jesus with ecstatic adoration as he kneels awkwardly on the earth.

We remember that John is both eagle and rooster with his penetrating and mocking mind, his combination of beyond-the-world tragic sense and in-the-world comic tenderness. The scream of the eagle and the laughter of the cock resound throughout the country of John’s Gospel. He remains the complex, elusive poet, proceeding slantwise in telling the truth of his experience. At bottom, because he is both follower and writer, John’s vision is paradoxical. His encounter with Jesus transports him into an ecstatic realm and, at the same time, throws him to the ground in an ironic world that demands he find words for the Word.