Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

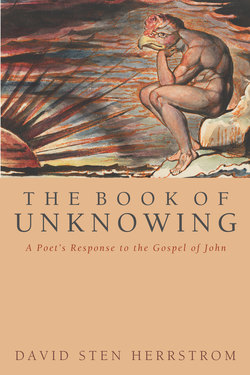

Hands

ОглавлениеJohn wants to feel a hand brush his cheek, a hand lie on his forehead. He wants to be lifted up in the strong hand of Jesus. “The Father loves the Son, and has given all things into his hand” (John 3:35). Jesus’ words are John’s words uttered from the depths of his being. We hear in them the universal human desire for comfort and security. John would give himself wholly into Jesus’ hands, having never lost the child’s desire to place a small hand in the father’s.

But the yearning for Jesus, a hero with power and wisdom beyond ours who will keep us in his hand is more than this. It is the aching desire for more life, the fullness of life, real life itself (10:28–29). Proffering immortality, the hand is a refuge for eternity (13:3).

Though master of the symbolic, John never lets go the physical hand. Its symbolic palm offers comfort and, as it did for Ezra, interpreter and scribe like the writer John himself, wisdom (Ezra 7:21). Yet its physical backside threatens—the hand raised throughout John’s book until it finally strikes Jesus (19:3).

Alone among the writers of Jesus’ life, John insists on hands becoming the object of our attention. The last glimpse we get of a favorite character, Peter, is Jesus’ prediction that old and dependent, he will “stretch forth” his hands (21:18). As John’s book ends, we’re left with the image of hands stretched out in need.

This simple, physical gesture crystallizes the desire that drives John’s book and its strangeness. We come to share his idiosyncratic gaze, and in it we find the writer John. “In the beginning was the Word,” but it becomes truth only in the flesh and ultimately in the art of John’s words. The details that he singles out take on a strangeness; by his power as a writer, they become new.

Art and life, John knows, dwell in the particulars of experience: the severed “right ear” of Malchus (18:10); the charcoal fire in the courtyard (18:18) and on the beach (21:9). Or when Jesus insists on washing the disciples’ feet, Peter blurts out like a child: “not my feet only, but also my hands” (13:9). These details arrest us in John’s book because of their very singularity. An eagle soaring in lyrical heights, John does not miss the smallest movement far below of a hand.

•

Jesus stoops down, as a hostile crowd becomes eerily silent, stretches out his hand and with his finger writes on the ground. At Jesus’ invitation Thomas stretches out his hand, while the disciples look on dumbly, and puts his finger into the bloody hole in Jesus’ hand.

These marks in dust and blood are John’s most singular. They go beyond language in a book babbling with talk and argument and interpretation, and pass into the realm of pure presence. No appeal here to anything greater or higher than the gesture itself. It does not require elaboration or explanation. For it is its own authority, and we can only witness.

With the woman taken in adultery, Jesus refuses a test; in the exchange with Thomas, Jesus accepts a test. In the former scene, refusal is rooted in faith, a complete and unfounded act of compassion. While in the latter, acceptance is rooted in doubt. Neither love nor faith can be established by tests; they can only be revealed in acts of compassion and commitment.

Simple acts of extending the hand, but both are outrageous. They are silent, for one thing, their power derived not from the word but from the infinite space before and after. They threaten to be more powerful than the book which contains them. Mere gestures, both acts shake the walls of John’s book and like Jesus walk right through without opening the door.

For another and more unnerving reason, they are intractable. Both the hand of Jesus in the story of the woman taken and of the man, Thomas, are as difficult to expel from our experience as grit in the eye. Two different but complementary perspectives: the one threatening public order, the body politic; and the other threatening private order, the body itself.