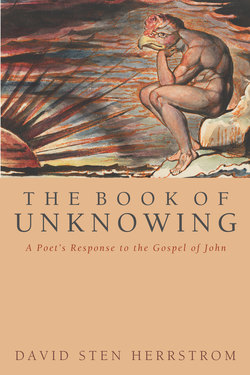

Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Light

ОглавлениеLight is time thinking about itself.

—Octavio Paz

Light walks the earth wanting to be courted like a lover. He does not oppose darkness because darkness has no real existence. For light, who has come into our world to be desired, darkness is not even a question. Light being wholly light cannot conceive it. Light is not opposition but attraction; he draws all to himself. Those who reject the lover, however, give darkness existence because their state of rejection is called darkness. The body of light knows only radiance. His name is Jesus.

John has fallen in love. And he writes a book about this being, whom he quotes more than once declaring: “I am the light of the world” (1:8; 9:5). In gesture and word, Jesus is for John incandescent. We can easily imagine him saying of Jesus, as Guy Davenport remarks about a character in one of his stories, “He eats light and his droppings are copper.” John’s dream of sharing light with Jesus at the table is fulfilled. And in an epilogue to his book he projects himself into a most moving scene of breakfast on the beach: Peter and Jesus breaking light together at daybreak. By an act of adoration John partakes of this light, feeding on the nourishing light, just as John the Baptist became by his love “a burning and a shining light” (5:35).

From the beginning, as John makes clear, light is life that gives life. Light is not a moral category but the substance of life itself. When the “Word was made flesh,” light became a body. And in the Word “was life, and the life was the light of men” (1:4). This answers the main question of our age, posed succinctly by the Argentine poet Roberto Juarroz, “Where is the light of a god propped against nothing?” And it is John’s fervent desire that those who witness this light walking the earth might like John himself fall in love with Jesus, which is to “believe” (1:7), and thereby share in the fullness of life that radiates from Jesus.

John’s yearning here extends throughout his book. He savors light in his prologue, repeating the word in an incantation, “and the life was the light of men; and the light shines in darkness” (1:4–5). Jesus echoes this in his own incantation at the end of the colloquy with Nicodemus (3:19–21) and later as the knowledge of Jesus’ imminent, gruesome death oppresses him (12:35–36). In John’s mind light and life are inseparable. John wants what we all want, as A. R. Ammons describes it in “Summer Place,” nothing short of a land “where tenderness would be so high it would transmit / light . . . and the rivers would / be flowing light and trees would sway with the fruit of light.”

•

John in love is why he refuses the traditional opposition of light and darkness. He inherited a dualism that pitted light against darkness. And the writer of Genesis reinforced this tradition. John, however, returns to the profound intuition of light not only as the very ground of life, but as the primal reality. Light did not drive out original darkness; instead, darkness was only given a name by the absence of light. Light came first in the creation of the world and in the radiant person of Jesus.

Rooted in this assumption is John’s emphasis on the love of light rather than the traditional war between light and darkness. His is a radical move. This is evident when we contrast John’s understanding of light to that of a contemporary community, the Essene’s. Their apocalyptic fears were projected into a war between the “Sons of Light” and the “Sons of Darkness.” Jesus, however, under great stress, implores his disciples at the end, “While you have light, believe in the light, that you may be the children of light” (12:36). John portrays this as an admonition to a personal act of love. The Essene community’s The War of the Sons of Light with the Sons of Darkness (c. 60 B.C.), in contrast, moralizes becoming “children of light,” turning the act into one of communal hatred. It demands that its disciples “Love all the Sons of Light” and “Hate all the sons of Darkness,” the basis for all genocide before and since. The traditional symbolism of light/darkness is used here as an incitement to war.

Jesus rejects this, as does John, and pushes back beyond the inherited symbolism to employ light as an inducement to a fuller life. The ethical overtones are still present, but they are inward and derived not from opposition but unity. By contrast, The War thrives on the traditional opposition, separating and demonizing, inflaming the passions of hatred rather than generating love.

The character of Nicodemus saves John and thus Jesus from this black-and-white fate. Nicodemus who came by night in the beginning of John’s book comes by day at the end loaded down with spices for Jesus’ body. A half-lit figure, he is to the moon’s “white fire” in P.B. Shelley’s phrase as Jesus is to the dawn, cooking breakfast for his disciples over a charcoal fire on the beach. Nicodemus and Jesus share this threshold existence between light and dark.

John, consequently, cannot bring himself to condemn those who do not love, for he knows that they are condemned already by their own lack of love. This is why Jesus is so ambivalent about judgment, stoutly maintaining that he has not come to judge, yet often sounding like the accuser. John underscores this ambivalence. He shuns absolutes, the easy binary categories of morality, as in his portrayal of Jesus bending down to write in the dust. Once John introduces Nicodemus, his love for this ambiguous figure will not allow him to judge. Thus darkness, though used symbolically on occasion, as in Judas’ going out into the “night,” is not absolute. There is no hell in John’s book. And this is owing to Nicodemus, the creature of John’s reporting who in turn shapes John’s creation.

To be “children of light” is to have within oneself, like Jesus and John the Baptist, light. John does not desire to follow the light, so much as partake of the light. For then this light emanates from the person. There can be no darkness, then, for the child of light. When “there is no light in him” (11:10), the result is night. It is left to Dante, a poet the equal of John, to continue the exploration of this phenomenon in his Divine Comedy. With sublime subtlety he leads us from the poor bastards in hell, doomed to seemingly infinite variations on a darkness of their own making, to the vision of Beatrice in paradise pouring from her the fire of love, the river of “living light.”

•