Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

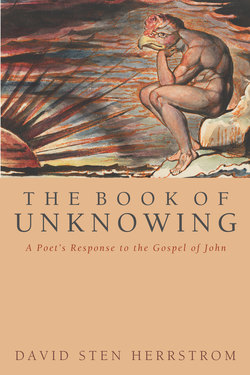

The Scarlet Experiment

ОглавлениеThe finger of Jesus touched the dust from which we were created, affirming our common humanity. Just so Thomas’ finger touches the blood of a specific individual, questioning the human. The hand of Jesus inscribes the ground, while Thomas’ inscribes the body itself. Jesus’ finger is a stylus making the word public; Thomas’ is a knife intruding into the private recesses of the Word. To question, Thomas must violate the body. He must, in Emily Dickinson’s brilliant image, “Split the Lark.”

His bloody act is intractable. It is as alien to the imagination as some dark custom of an ancient and distant culture. The conquered, missionized Aztecs were right in seeing behind St. Thomas their god Quetzalcoatl. His priests thrust their hand into a victim’s chest, which had been sliced opened with an obsidian knife, and wrenched out the still-beating heart. After the ritual killing the body was dismembered and eaten. No surprise that the Aztecs embraced the Mass, the ritual eating, at his own invitation, of Jesus’ body (6:53). Our mind cannot assimilate this thrust of a hand into the wound and red-drenched withdrawal, whether by an Aztec priest or Thomas himself.

Yet Thomas insists that he put his “finger right into the place of the nails” and his hand into Jesus’ side. Obligingly, Jesus invites him: “Reach out your finger and examine my hands; reach out your hand and put it into my side” (20:25, 27; trans., R. E. Brown). Thomas accepts. Did he seek the warmth of that wound? Did he seek assurance of the body’s sticky fleshiness? What exactly did he seek that his eyes and ears could not discover? In any case, we can’t help but imagine the consequences as he inevitably reopens Jesus’ wounds. His act would, of course, “Loose the Flood” in Dickinson’s words, “Gush after Gush.” Again, John asks us to accept the outrageous.

We resist. Where we are drawn into the trembling woman’s scene with Jesus, we are repelled by Thomas’ literalism and intimacy. Contrary to what we would expect, all of us being somewhat skeptical by nature, we are made uneasy by Thomas’ challenge and Jesus’ acceptance. Ostensibly this is a test, what Dickinson calls his “Scarlet Experiment.” But we realize in the end that it does not prove anything. Faith like compassion is beyond testing.

Yet his experiment succeeds in one respect. Thomas confirms the bodily presence of Jesus. From Jesus’ perspective the experiment was to be a test deciding belief or unbelief in an idea of life, “eternal” life. From Thomas’ point of view it was to determine identity, a test deciding belief or unbelief in the reappearance of the material body, living flesh and blood. So Thomas’ bloody experiment either falls short of or presses beyond belief and unbelief, just as Jesus’ writing in the dust pushed beyond good and evil.

•

We are left with an act, then, as intimate as sex. John forces on us a Thomas and a Jesus who insist on this extreme of the personal. John makes us feel like voyeurs. And we can’t take our eyes off them, though we cannot fully comprehend or assimilate such gory intimacy. We are in a melodrama, though moved by Jesus’ gentle acquiescence in such a bizarre request. At the same time, we find ourselves in an S&M nightmare.

This violation of the body is as hard to swallow as that of the body politic earlier, the dissolution of the Law. John pulls no punches. He throws the profoundly radical scene in our face. He says, in effect, “If you cannot accept this heart of the Jesus story, then you cannot accept the story’s Jesus.” With Thomas, John insists on the physicality of this scene. He wants our belief just as Jesus wants Thomas’, but willfully puts up barriers to our assimilating this radical core of his book.

John sets us up by having Jesus walk through the wall of the room where the disciples are gathered (20:26) just before he invites Thomas to make his experiment. John relishes here the wonderful irony of an apparently immaterial Jesus walking through immaterial walls and then asking that Thomas thrust his material hand into Jesus’ material body. This is no spirit body. The visage and voice apparently not being persuasive, John insists on the actual hand in an actual wound.

A macabre scene, we want to laugh and flee at the same time. It would truly be comic if not for the earnestness of Thomas. Yet we find its straightforward physical actuality painful to visualize. Consequently, the scene is a risky move on John’s part. It works, however, because the scene very effectively maintains tension by not resolving our contradictory impulses of disgust and laughter. A dilemma the medieval painters felt in its fullest force. They were clearly uncomfortable in depicting this scene, pulling back from it—Thomas’ finger only touching the wound, almost daintily, not thrusting into it—or gazing voyeuristically into the scene—rendering it grotesque by details that leave us teetering on the edge of hilarity.

John refuses to allow us an escape from his scene’s tension, being a resolutely honest writer. Thomas’ request could understandably be taken as metaphoric, but John has Jesus accept it without hesitation as literal, as do the disciples. John is not content to build this surreal scene on realistic detail, but revels in the starkly literal. To escape this, we want in some recess of ourselves to preserve the figurative, Jesus as the Lamb shedding metaphoric blood. Yet here is emphatically not the Word of the opening of John’s book but the word made actual flesh. His collapsing the metaphoric into the literal is compelling by its very strangeness.

The scene calls the utility of language into question, then, exploding our tacit agreement about what is literal and what figurative. Witnessing Thomas’ encounter with Jesus, we are repelled and fascinated not only by its insistent physicality but by language bent beyond its breaking point. Thomas’ act at Jesus’ invitation goes beyond belief and disbelief, beyond language itself. For in the end is the body.