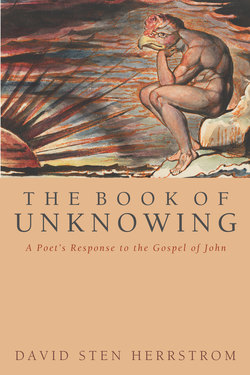

Читать книгу The Book of Unknowing - David S. Herrstrom - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Nicodemus

ОглавлениеNicodemus wrestles with John for his book and receives a name. Neither a believer like John, nor a teacher like Jesus, he is the questioner.

Once brought on stage, we are powerless to dislodge him from our imagination. A problem John shares. After introducing Nicodemus early in the book, John must bring him back in the middle and again at the end. Nicodemus is the man on the periphery who will not go away. He is both a central and marginal figure. Ultimately, he takes control of John’s book, for we find ourselves, despite the writer’s efforts, reading it through the lens of Nicodemus’ questioning character. And to paraphrase Jesus, the central shall be marginal, and the marginal shall be central.

We are what we love. Character is defined by desire, and Nicodemus’ desire is not for belief but knowledge. Yet desire alone is not sufficient. “The self forms at the edge of desire,” as Anne Carson puts it. Desire saturates character, but the true self cannot precipitate without risk. Nicodemus risks his position in search of knowledge. Driven by curiosity, he seeks Jesus out, away from the crowd and hangers-on, away from the support of his own tribe. The questioner stands outside any vocabulary that purports to define the world in total.

While Jesus desires to die, and John desires to live, Nicodemus alone desires to know. He goes out of his way to meet with Jesus. In their colloquy by night (3:1–21), however, he stands apart as the questioner. Likewise, as challenger, he stands outside the temple coterie (7:45–52) just as he does Jesus’ circle, not fully leader of the Jews and not a follower of Jesus. Yet his questions to Jesus early on haunt the rest of John’s book and make Nicodemus a central figure. We are not surprised, then, when he shows up after Jesus’ death to honor him with a gift of spices (19:38–42).

Call him Nicodemus the uncertain, disinterested, always engaging and disengaging; oscillating between the center and the circumference, between Jesus and those who write Jesus off, his brothers, friends, ex-followers, enemies, even baffled strangers like Pilate who encounter him purely by chance. Nicodemus savors uncertainty. He lingers in the twilight where no categories are firm, no vocabulary final, reminding us of Bulkington in Melville’s Moby-Dick, who inspires the observing narrator and shipmate to assert that “in landlessness alone resides the highest truth, shoreless, indefinite as God.” Like Bulkington, Nicodemus is the secret member of the crew.

•

From Nicodemus’ position on the periphery, when the Jews are shouting Jesus down in the temple, he brings them up short with a single question: “Does our law judge any man, before it hear him, and know what he does?” (7:51) I want to cheer. What a dramatic reappearance of Nicodemus in the middle of John’s book, bursting on the scene again at this point of tense interaction and sharp interpretative interchange.

Nicodemus comes back into the story with a reaction that we didn’t get when we first met him questioning Jesus. There the conversation ended with his long, almost suspended silence. We wanted more. What was Nicodemus thinking as Jesus’ words echoed in the night air? (I’ve “discovered” three letters from Nicodemus to John that perhaps answer this question, which inventions follow this chapter, a “Fictive Interlude.”) Here, as a result, Nicodemus’ reaction to the crowd feels like a resolved chord. He was the cool questioner, withholding judgment, insisting like a skeptic on results, actions. He didn’t buy Jesus’ story, but has clearly hung around, observing him closely, and now on his behalf asks for fair play, though keeping his distance.

In the scene that follows in the same temple, however, Nicodemus chooses silence. When Jesus and Nicodemus and the Jews reconvene early the next morning (8:2), the Jews bring before Jesus a trembling woman taken in adultery. Nicodemus hovers just outside the action. A ruler of the Jews, but in contrast to the day before in the temple, Nicodemus keeps silent. He provides a ground base of questioning for this extraordinary scene of power and compassion. John reinforces our sense of his presence by invoking at the end of the scene (8:12), as he had at the end of Nicodemus’ colloquy with Jesus earlier, the Prologue to his book, which contains the whole and marks both these encounters with Jesus, Nicodemus’ and the adulterous woman’s, as pivotal.

Though he is marginal, neither fully Jew nor disciple, friend nor stranger, Nicodemus is the speck of dust in John’s eye that he can’t get rid off. He wants him to believe, but John’s integrity as a writer won’t let him fudge when Nicodemus does not become a follower of Jesus, and he gives us the questioner. Nicodemus’ resolved and detached character takes on a life of its own that cannot be made into what it is not. He chooses knowledge over belief, and even John in his own book cannot change this.

•

A knower but Nicodemus the outsider acts boldly. We’ve seen him speak out, while maintaining his distance, but in the end he simply acts. And what an action, it is an unforgettable gesture. As pure and extravagant as Mary’s gift of perfume, Nicodemus brings 100 pounds of embalming oil with “myrrh and aloes” (19:39) for Jesus’ burial. He does not ask for fairness in the treatment of Jesus. It’s too late for that. He simply acts, insisting on honor, courageously joining Joseph of Arimathea in wrapping Jesus’ body for burial. Extraordinary, this last glimpse, John giving us a Nicodemus in silent, fragrant action.

And John subtly contrasts the knower and the believer in this scene. The “secret disciple” (19:38) Joseph of Arimathea does the talking, negotiating with Pilate. Nicodemus does not speak. After Joseph of Arimathea succeeds in getting Jesus’ body, Nicodemus joins him. But where are Peter and the others?

It is only the two outsiders who have the courage to act, one out of belief in Jesus and one out of respect for Jesus, for the knowledge he clearly possesses. Joseph of Arimathea must speak to come clean, to declare who he is. Out of tremendous personal integrity, Nicodemus must act to pay homage, but at the same time this allows him to maintain ambiguity. Though present, his position can’t be resolved. More than admirer, certainly, yet not disciple or we would have heard. And the disciples are noticeably absent. Their belief results in embarrassing absence while, ironically, Nicodemus’ knowledge results in extraordinary action.

The disciples’ absence, of course, heightens the power of Nicodemus’ presence. Where Joseph of Arimathea appears out of nowhere, John carefully makes Nicodemus’ appearance a climax, intensifying as well the drama of his gesture. He becomes bolder as he observes Jesus under a wider variety of circumstances. And possibly Jesus’ defining action for Nicodemus was the forgiveness shown the adulterous woman. Witness to such manifest power, Nicodemus realizes the true depth of Jesus’ understanding.

Regardless, after he meets Jesus, given continued observation, Nicodemus’ emergence is inevitable. When we first see Nicodemus he speaks privately in a night scene. When we see him again, he raises a question publicly in broad daylight and, finally, joining Joseph of Arimathea, he goes beyond words and simply acts publicly.

A fine reversal of the first scene in the last epitomizes Nicodemus’ stance. As John limns his progress with just a few strokes, we’re aware that in the first scene Nicodemus is implicitly accused of lacking life, while Jesus is volubly alive. In the last scene, however, Nicodemus is beyond John’s grasp and emphatically alive as, in silence, he respectfully touches the dead body of Jesus. And unlike Thomas and Mary Magdalene, he touches Jesus’ body on his own terms.

•

Once John grants Nicodemus life, the energy of the center that for John is always the character of Jesus must be shared. We catch Nicodemus only out of the corner of our eye, but when we do, he becomes a center himself, pulling John’s interest to what had been the periphery and making this figure of knowledge central.

John loses control of Nicodemus early on. The narrator begins straightforwardly to introduce his colloquy with Jesus, announcing that “There was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews: The same came to Jesus by night, and said unto him, Rabbi, we know that you are a teacher come from God: for no man can do these miracles that you are doing, unless God be with him.” But subtly Nicodemus moves to a central position in John’s book. “Jesus answered and said unto him, Verily, Verily, I say unto you, Unless a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God. Nicodemus says unto him, How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born?” (3:1–4).

Though Nicodemus addresses Jesus with respect, conventionally as a Rabbi, his words are tinged with irony. Instead of saying simply “I know,” he addresses Jesus as a representative of others, a “ruler” of the Jews in fact, saying, “We know that thou art a teacher come from God” (3:2). I hear his greeting as more a question than a declaration. As a consequence, we view Nicodemus immediately on an equal footing with Jesus, instead of an uncritical admirer come to fall at his feet in homage. Jesus’ response accepts this equality. He makes clear in a rather brusque manner that Nicodemus’ assumptions are unacceptable: “Jesus answered, Verily, verily, I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter into the kingdom of God. That which is born of the flesh is flesh; and that which is born of the Spirit is spirit (3:5–6).”

The oracular “Verily, verily” shifts our sympathy away from Jesus to Nicodemus where it remains throughout their colloquy. We identify with the questioner. For Nicodemus’ remains the key question of John’s book, “How can a man be born when he is old?” Rather than Pilate’s, “What is truth?” The former question is about experiencing and obtaining knowledge, the latter about seeking and believing. Pilate accepts the language of Jesus, while Nicodemus explores his language. Nicodemus asks about Jesus’ way of speaking, not what Jesus is speaking about.

Jesus’ method is apparent. John uses this scene to make it explicit early on. He invites Nicodemus to accept a new vocabulary, not “born” of the womb as we customarily understand the term but “born of the Spirit.” By this means Jesus attempts to construct an edifice of language from which there is no exit. John shows us Jesus at work building this structure: statements layered with carefully placed questions; oracular rhetoric raised on a foundation of concrete imagery; rigid categories, such as flesh and spirit, cut from steel. Jesus is the master builder.

Just as the breath of the wind through the courtyard takes his attention, however, Jesus is undercut by the disinterested Nicodemus, whose reasonable questions asked with calm, profound respect haunt us. Our sympathy shifts to Nicodemus. At the same time, he shares Jesus’ power of language building, who in turn borrows his irony, “Art thou a master of Israel, and know not these things?” (3:10).

Despite John’s orchestrating the scene to emphasize Jesus’ power, skillfully moving from their dialogue with its threshold imagery of birth/water to Jesus’ monologue with its categorical imagery of belief/truth, a counter movement undermines this power. Seen from Nicodemus’ exploratory, questioning perspective, we realize that the edges of Jesus’ new terms are not as sharp as they first appear. Perhaps they’re modeled in clay rather than cut from steel. In the end, during Jesus’ monologue, we are distracted by what might be revolving in Nicodemus’ mind. And after Jesus stops, the continued silence of Nicodemus hangs over the scene like a thunderhead.

John dramatizes the fact that Jesus’ power is inseparable from his mission of radical redefinition. Nicodemus’ night colloquy with Jesus, then, is critical to John’s book. First, because it makes explicit what is at stake. A new vocabulary is offered by Jesus, an attempt made to establish new categories, declare where the edges of things are in the new world inhabited by John’s Jesus. Second, these very edges are undercut by their language, the ironies they exchange where edges blur. Just as Nicodemus is both on the inside and the outside, so none of the distinctions that Jesus makes—flesh/spirit, earth/heaven, light/darkness—remain hard. Almost as soon as these categories are defined, they begin to shift like the wind.

•

Brilliantly orchestrated, the pivotal scene unfolds in three movements of increasing length and decreasing complexity, as Jesus’ vocabulary narrows to a chant of “belief” and “light” and his monologue dominates. John signals us when a movement begins and ends, using the close of each for emphasis. All three movements begin “Verily, verily” (3:3, 5, 11), the first two ending with Nicodemus’ question. Significantly, the last movement ends not with a question, since Nicodemus has dropped out of the conversation, but with a declaration about “doing truth” in the light. This returns us to John’s Prologue, his opening hymn to the word and the light, signaling the importance of this scene.

As we have seen, Jesus’ program begins in the first movement, redefining “birth” as the necessary groundwork for the redefinition of “flesh” and “spirit” in the second. He insists that “flesh is flesh” and “spirit is spirit,” attempting to draw a clear line between the two. At the same time, Jesus ends this movement with the powerful but ambiguous image of the wind, and John dramatizes the word play (wind/spirit), which together undermine any rigid distinction between flesh and spirit.

Nicodemus’ question, furthermore, “How can these things be?” wins our sympathy. While we’re drawn to Nicodemus, we are distanced by Jesus. For his withering irony in response, “Art thou a master of Israel, and know not these things?” betrays a lack of patience. Jesus presses his program hard in this second movement, but Nicodemus’ genuine question breaks the momentum. He is no straight man, and his question dogs us throughout the rest of the book, which is why John introduces it here.

Nicodemus does not deny Jesus’ assertion. Instead, he asks in so many words, “in what way are you speaking of these things”? Yet Jesus’ tone shifts immediately to the hortatory with a flurry of premises, a rhetoric that Jesus wants Nicodemus to adopt because once the new vocabulary of “birth” and “spirit” is accepted, Jesus’ conclusion follows.

•

The dialogue at this point, as if to consolidate his renaming power, becomes a monologue. John gives Jesus the last word, a long speech that does not end with a question. Jesus begins authoritatively, asking a question himself, albeit rhetorical, about understanding “earthly” and “heavenly” things (3:12). At the same time, he picks up Nicodemus’ irony from the opening of the scene, where he had addressed Jesus in the first person plural, “We know that you are. . . . ” Likewise, Jesus shifts here from “I” to “We.” More important, while driving home the firm distinction between earth and heaven, emphasizing their difference by the contrast between ascending and descending, Jesus repeatedly names the “Son of man.” And he dwells in heaven as well as on earth. The Son of man participates like Jacob’s ladder or the serpent that Moses lifted up (3:14) in both the earthly and the heavenly, blurring their outlines. What first seem to be hard categories prove to be soft.

A similar dynamic operates at the end of Jesus’ monologue. Working himself into a fine chant on the word “belief,” he climaxes with a demand for belief in the “name” (3:18) of the Son of Man/God. Anyone, not just Nicodemus could be confused, for by now this name signifies God and/or man. Jesus breaks the law of the excluded middle. In building language with Nicodemus in their contra-dance, Jesus dissolves the categories of flesh and spirit, earth and heaven, even man and God.

Returning at the end of his monologue to the primary categories with which John opens his book, Jesus makes a final attempt to draw the edges clearly. He turns to the consequences of not accepting his new vocabulary, such as “birth,” and its concomitant binary categories of thought and life, such as “flesh” versus “spirit.” What opposition could be clearer than light and darkness? An ancient dualism, Jesus turns it to his own ends, redefining it in terms of a person “come into the world” who courts the world and is either loved or rejected. In a wonderful move Jesus turns an abstract, traditional metaphysical duality into a drama of desire. Earlier Jesus has said he is not concerned to “condemn the world” (3:17) for not believing on the “name.” Now we understand why.

For the world, if it rejects the lover named light, suffers a condemnation that arises from within:

And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil. For every one that does evil hates the light, neither comes to the light, lest his deeds should be reproved. But he that does truth comes to the light, that his deeds may be made manifest, that they are wrought in God (3:19–21).

A deft move, Jesus avoids condemning, as does John throughout his book, by simply pointing to the condemnation that dwells in all who do not choose to inhabit his new edifice of language. And self-condemnation, we know, is the worst damnation.

This strategy enables Jesus to avoid the trap of dualism, inherited from the tradition of light/darkness, while constructing new categories with which to understand the world. Yet this advantage cuts both ways. Turning back on him, his strategy erases any sharp line between the categories. For light is reality, a bodily reality, the light in the beginning and in the end, while darkness is defined wholly in terms of this reality. Darkness ultimately has no substance in itself. The one who does evil does not finally, therefore, love darkness. Rather, he “hates the light.” Thus darkness is fundamentally the absence of light.

Jesus speaks of desire that forms character, those who “come to the light” like lovers. With John we appreciate the irony of Nicodemus the lover of light coming to Jesus by night. Later John uses the word symbolically, noting pointedly that Judas, after betraying Jesus, goes out into the “night” (13:30). But John clearly savors the night scene here for its dramatic effect. Using it counter to convention, darkness reinforces the note of affirmation at the end of Jesus’ monologue, where in a lesser writer we would expect condemnation. In the silence that John gives Nicodemus, we become aware that he knows but does not believe on the one “name.” For Nicodemus resists a single all-defining vocabulary with its rigid categories by which we are intended to understand our experience.

As a lover of knowledge rather than belief, Nicodemus is content to visit Jesus’ house of language and learn, but not to move in because it is ultimately too confining. The one Word by which “all things were made” and “without him was not any thing made that was made” (1:3) is profoundly and disturbingly exclusionary. No spiders or Visigoths need apply.

Nicodemus’ questions lodge in our mind for the remainder of the book. Their bringing language into account, riding the edge of figurative and literal, categorical and ironical, ultimately results in their going unanswered. That is, we find ourselves viewing all that John presents subsequent to this scene through Nicodemus’ eyes. His blurring the edges with irony that Jesus picks up and adopts, his silence as the categories dissolve, not light versus darkness but light and absence-of-light, finally prevails in this pivotal scene that forms the climax to the first part of John’s book.

Nicodemus, in short, consistent with his desire to know and his disinterested character, obliquely revises Jesus’ language and with it John’s book. Fittingly, in a scene that forms the climax to the last part of his book (19:38–42), before the resurrection and reunion, John brings Nicodemus and Jesus together again. And true to character, the ambiguous Nicodemus’ very presence questions the language of John’s book. If as the disciples say, they “believe,” why aren’t they present? So he continues to haunt us as we last see Nicodemus, now by daylight, bent in silence wrapping the dead body of Jesus.