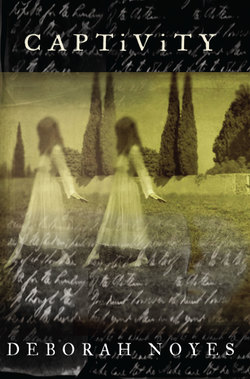

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

6 The Invisibles

ОглавлениеMa and Maggie arrive in Rochester the day after Leah’s household relocates to Prospect Street. The piano movers are on hand. They’ve positioned the instrument wrong, and with Leah noisily redirecting them, and Kate trying to keep the cat from underfoot, and Lizzie hollering for the sake of it, and Ma and Maggie and the hired coachman lugging bags and parcels indoors and tracking in mud, the reunion is unceremonious at best.

No sooner has Leah hustled the piano men out again than she turns to interrogating Ma, who has yet to remove her shawl. Maggie feels a terrific urge to race out after the coachman and have him see her home again. But where is home? Sobered, she helps Ma with her overclothes as Kate and Lizzie stand stupidly by, tormenting the cat.

Leah nods over the piano keys, tapping out tuneless notes and wincing. “What news at home?”

Hanging Ma’s things, Maggie glances up under her lashes at Kate, her favorite person in the world, and her look goes unanswered.

Ma seems pleased that much-older Leah—twice married and twice estranged—speaks easily of “home” when the cottage in Hydesville never was her home, but she’s having trouble gathering her thoughts.

So Leah intrudes on them: “What more have the men found in the cellar?”

Ma begins to gush like a stuck pig, like the cellar floor when the men first took their picks to it. She wails of the crowds at both the cottage and David’s; of the digging that just goes on and on, weather allowing; of the mess and disorder and Ella running wild in the thick of it all; of David and Elizabeth with their weariness and worn nerves; and of the fickle ghost and the baffled investigators.

The more panicked and weepy Ma becomes, the more roused seems Leah. Maggie can almost feel her circling, assessing the story’s edges, searching for a place to turn her claws in.

Chilled to the bone from the canal ride, Maggie sits on her hands to warm them. She’s trying to keep still, marveling at her sister’s composure.

Now and again Leah taps out a note with her thumb—C, E, F, A—that wilts on the air. To call in a tuner will be an extra expense, but Leah makes her living teaching piano. She can teach even the dumbest brat to master Mozart because her patience never flags.

If Leah was upset that no one sent for her when it happened, that she had to hear the news like a stranger from neighbors and journalists, she didn’t let on. Instead she hurried to Hydesville and made herself useful. “Don’t cry, Ma.” She stands now and crosses to their mother, taking her hand, patting it like a puppy. “You can stay here as long as you like.” Leah takes them in one by one, all beneficence. “You all can. But you believe in this spirit? These spirits?”

Maggie stares forward blankly. With Kate and Lizzie like strangers, there is no safe gaze to seek refuge in.

On the other hand, their ghost has made Maggie brave. Always, in the past, she was the cautious one, the one who planned and recorded, who said but rarely did. Tell me a tale, Katie begged when they were children in Canada. You have a secret, Maggie! Tell it now…. And Maggie told, in grave whispers, for it was one way to hold her sister still and present. Kate was ever in motion, whooping, chasing crows from the fields. She ran whirling and the birds seemed not so much afraid as under her sway. They rose thundering together into the slate-gray air, and Maggie half-feared her sister would rise with them, but Katie only laughed and mocked her care. Kate was and is the most careless, uncomplicated creature Maggie knows, and Maggie loves her well for it.

At the cottage and at David’s, “the girls” rarely spoke of the spirits or planned their path but moved together like dancers, step step turn. The music became a thing outside them, spectral music with a life of its own, and whosoever might stop the music could be damned.

When Leah came and took Kate away to Rochester, leaving Maggie behind with Ma to suffer the tedium of David’s farm, Maggie thought her heart would burst, but she rallied, soldiering on alone. Thanks in part to “A Report of the Mysterious Noises Heard in the House of John D. Fox, in Hydesville, Arcadia, Wayne County”—the very document, penned by a Mr. E. E. Lewis, that alerted Leah in Rochester to their predicament—western New York was alive with speculation. Whether born of trickery, fear, superstition, or the lot, the pamphlet held, “if any one has been able thus to deceive a large, intelligent, and candid community for a such a length of time as this has been carried on, it certainly surpasses any thing that has ever occurred in this country or any other.” The Fox sisters were on everyone’s lips, but their own family—Pa now deferentially referred to it as “David’s household”—didn’t speak of the cottage, even in rare moments of privacy round the kitchen table. It was as if Maggie and Kate and their parents had never lived there, had never been the people in Mr. Lewis’s pages.

While investigations ensued and everyone and his mule whispered of her exploits, Maggie Fox, down on the farm, had none but the impersonal dead to confer with. Ma’s lip quivered when she tried. If Maggie so much as hinted, Ma wept morosely and groped for her Bible.

In spite of all, Maggie got by, and so did Mr. Charles B. Rosna—by no means loquacious but present just often enough to keep his audience on edge.

When Leah wrote to say that she’d secured rooms in a two-family house on quiet, tree-lined Prospect Street in Rochester’s fashionable Third Ward, and that Ma and Maggie were welcome to join them there, Maggie’s joy was fierce. So was her passion to be with Kate again, to hold her sister and giggle and fall again under the spell of them.

But it’s instantly clear that things won’t be the same at Leah’s.

Ma kneads an embroidered hankie—one of Kate’s, full of jagged lightning stitches—in one raw, red farm-wife hand. “You know me, girl. I’m sorry for this trouble. It’s our grave misfortune to live in such a house. I believe only what I’ve heard and what these here and your father and our good neighbors have heard, and I pray for deliverance.”

“Margaretta,” Leah barks, riveting them all. Kate even stops toying with the cat’s tail. “What do you say?”

“Marta Weekman—”

“I don’t care what Marta Weekman says. I’m asking you.”

Maggie keeps her eyes on the ginger cat in Kate’s grasp, which emits a noise between a snarl and a belch and flicks its tail. Her gaze darts north in desperation, and at last Katie meets her eyes with a flickering smile. The world is instantly warm and wide again, as if the sun, withholding, has consented to rise. “I told you,” Maggie counters. “Ask the ghost. He keeps few secrets, it would seem.”

“And very late hours!” Leah says with altogether too much satisfaction. “Tell them, Katie.” She nods brightly at Ma, giving Kate no chance to do as she’s told. “We’ve had … a few visitors of our own. Sit. We’ll say all about it.”

The place in Rochester’s Mechanics Square, it turns out, is as haunted as David’s house, and the cottage before that. It only took the right residents to notice.

“We were scarce out of Hydesville,” Leah begins, swollen with self-importance, “and still on the canal when the trouble began. There we were, minding our business, dining with the other passengers, when the spirits went to town with a great show of rapping. Then and there. The table jumped, and water came splashing from our glasses, but with the noise of the boat going through the locks, no others noticed. Thank heavens.”

Ma frowns determinedly.

“We got home to Rochester around five P.M. Kate and Lizzie went straight out to the garden, I remember. They weren’t gone long when I heard a noise.” Leah sighs, gathering strength for the telling. “Like a pail of bonny clabber being dumped from the ceiling onto the floor. There was a terrific jarring after that, and the windows rattled—I’ll never forget it—as if we were by a battlefield. As if someone had fired off heavy artillery. It shames me, but I was paralyzed by fear. The girls rushed in, all wonderment, and walked me to my bed. There we huddled under the blankets, much alarmed, trying to sleep, but the moment the candle was extinguished the children screamed. Do you remember, girls?”

Both nod, a bit too dutifully, Maggie thinks.

“Lizzie said she felt a cold hand over her face and another stroking her shoulder and her back.”

Maggie looks to Lizzie, who can’t check a self-satisfied smile. The poor housecat has given in to its fate and gone limp and tender in Kate’s arms. Perhaps to hide that gloating smile, Lizzie mimics the cat, jabbing her forehead into the crook of Kate’s neck, craving affection. Kate again seems as distant and mysterious as the moon.

“So I took out the Bible and read a chapter, and while I read, the girls continued to feel touches. I never did, I confess. Finally we slept—I won’t say easily. We woke with the sun to the smell of roses. The birds were singing in the trees of the public square. The night now gone seemed unreal. I kept my own counsel but had my doubts, and toward evening, Jane Little and other friends came in to spend an hour. We sang and I played piano—” She looks around for impact, lowers her voice. Lizzie’s eyes widen as if she’s hearing this for the first time. “And while the lamp burned, I felt the throbbing of the dull accompaniment of the invisibles keeping time to the music, though the spirits remained kindly concealed so as not to alarm the company. We retired at ten,” Leah concludes—at least Maggie hopes this is the end—“and slept quietly for two hours.”

“And then?” Maggie demands, predicting an encore.

“And then …” Leah draws out her words in agonizing fashion “… woke with the house in a perfect uproar.”

Leah rises out of her chair. She starts stomping about with her hands moving like a mime’s to narrate how doors opened and closed in the dark. “Someone, followed by a great many others, walked up the stairs and into our bedroom, jostling and whispering. All I can figure is that it was some kind of show … with pantomime and clog dancing and raucous clapping … and then their footfalls moved away and downstairs again, the doors thumping closed behind them.

“On it went,” Leah says, “night after night, the whispering, giggling, and scuffling of this spectral assembly. There were death struggles and murder scenes of fearful character—I dare not describe—but in time it was as if we dawned on them, slowly, and they included us. They gathered in strong force around us.”

Ma listens, transfixed, and Maggie can’t but wonder: Why would Leah lie? She isn’t the better part a child, as Kate and Maggie are. Despite Leah’s wry pragmatism and occasional inclination to wink or stoop to child’s play, she’s a grown woman, dour with her days’ burdens. Why would she lie?

Maggie must conclude that Kate and Lizzie have carried on without her, which leaves her feeling even more out of place and out of sorts than when she arrived. These spirits are not Maggie’s. They are no part of her design.

“It’s useless,” Leah sums up grandly, “to record all that’s come to pass these last few weeks. At length I engaged these rooms. This is a brand-new building, I’ll have you know. Construction’s just completed. There were no former tenants, so it harbors no history, no crimes. Come,” she says brightly, “let’s have a look around and see you settled. Ma, you look exhausted.”

Is it any wonder? Maggie thinks expansively. Lonely and tired in view of Kate and Lizzie, their tittering and giggling, Maggie lags behind on the tour. Things were difficult and dull at David’s, and then that long journey in on the packet, and here they all are, competing warily for some prize she can’t name.

Leah points out that the house is really two houses on a single foundation. “The cellar’s there, and this kitchen staircase leads up to the second floor and the dining and sitting rooms. On the third floor, we’ve just the one long room that runs the length of the house. We put three beds there and curtained off a space for storage.”

Maggie hears Leah’s tour voice, traveling along with their footfalls upstairs, but she’s stopped short in the pantry. It looks out on the fenced back garden, but beyond that, plainly visible from the pantry window, are the bleak stony tips of monuments. Her mind reels and orients itself. Prospect Street. That must be the Buffalo Burying Ground. So much for “no history,” she thinks, a smile twitching on her face.

She’ll have to work quickly, she knows, and with great energy to draw Katie back from Lizzie’s sway and Leah’s. It’s always the way: when the other two get their hooks in, she has to lure and coax and charm Katie back.

But yes, Mr. Rosna has made her brave. If Maggie could navigate David and their parents and the never-ending flow of curious strangers, reporters, and investigators back at the cottage, she won’t be cowed by Lizzie now. Lizzie’s no match for Maggie Fox, even if Leah is.

Now that Maggie is home again—home will ever be with Kate—she’ll lie awake nights studying what she can make out in moon- or starlight of her sister’s turned-up nose with its spray of freckles, the sweet mouth with its habit of holding untruths, and feel an awed pulse of gratitude.

Home.

All is quiet until midnight, when distinct footsteps are heard moving steadily up the stairs and into the little green-curtained storeroom. From within, sounds—shuffling, giggling, whispering—the spirits, muffled in chintz, anticipating their own mischief. Out they come and give the beds a shake, lifting the sleepers off the floor, letting them down with a bang, patting them with cold hands before retiring again to what the Fox women will dub “the green room.”

“Can it be possible?” pleads Ma, in the dark. “How will we live and endure it?”