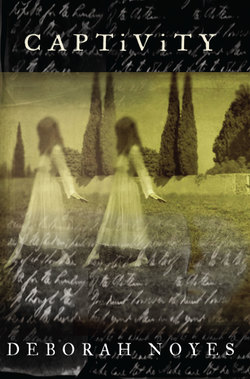

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 18

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

11 No Wish to Be Right

ОглавлениеClara isn’t surprised when the girl bursts in again without warning. The other one was just as brash till Clara grabbed her wrist one morning and warned in a tone of seething civility, “You will not enter this room again without knocking. Do you understand?” Clara never bit or scratched the hand, as rumors had it, but she might have done, and that was enough. Lizzie—the other one—has been timid and quiet ever since, though it taxes her nature, clearly.

Father insists these girls be treated with respect. “These aren’t ordinary servants, Clara, but the beleaguered daughters of friends in our circle.” By our circle, he meant his, of course. “They’ve been under tremendous pressure and require our support and tolerance.”

“And for this we pay them?” she asked.

Clara does her best, but she can little tolerate—much less support—some bright young body flitting about her room every day, her room, like a trapped hummingbird reeking of nectar.

But this Maggie Fox does seem a rare species.

Clara sits unnaturally still in her corner chair, squinting over a book, and it takes the girl a moment to ferret her out. She throws open the curtains again, all insolence, and the room blooms with dusty light. “You’ll ruin your eyes.”

Clara feels her own wrath, even if the child doesn’t. “I may have mentioned that my mother died when I was born….”

Maggie Fox looks up woefully under dark brows as if to say, “No, you didn’t.”

“I got on rather well without her.”

“I doubt that—”

“I’m saying, of course, that if I wished the drapes to be open, I would open them. I thank you, but I’m not an invalid. Not yet.”

“You’re welcome,” Maggie Fox says gamely, and it’s only for her father’s sake that Clara protests no further. She’s spent her lifetime reining herself in, not for society’s sake but for her own; she has a knack and a preference for revealing next to nothing about herself.

But this girl can communicate with the dead, people say, with those dead and gone and gravely silent. And now this same witless creature is trailing plump fingers over the line of seashells formerly concealed on Clara’s windowsill. “They’re pretty,” she croons. “Did you collect them?”

“Pretty”—Clara crosses her hands stiffly over her lap—“is a cheap word. Worthless. I’d advise you to relegate it to the cupboard with your dolls. Together with nice and good. People will expect more of you from now on.”

But words don’t sting this one as they did the other. Maggie Fox stares back at her—curious, expectant—and then lifts a shell and peers into it as if it were not dry and barren, as if there might be life there yet.

“I collected them years ago.” Clara’s not sure why her voice, persistent as grief, issues like a stranger’s from her hoarse throat. Casting back hurts, as green leaves hurt in springtime because they are too loud and bright. It was her nature, as in Mudeford with Will, to pluck up the downed feather, slip the smooth pebble in her cuff, a habit that bound her to him in memory, but she came to scorn the impulse to collect. It became tiresome as fashions do: fern cases and seaweed albums; parties of earnest ladies armed at the seaside with jam jars, prying up anemones from rock pools. “But I’m glad to have them now.” Glad because the door is too far away for me to reach. My arm is a weight. My fist is clenched. Because there you see every trace of him, all that’s left.

“Because they remind you of England?”

Clara fixes Maggie Fox in her hard gaze. “I need little to remind me of England.” She taps her forehead. “I’ve hardly left it.”

Did that sound pitiful? Despondent? She draws back. She will not give herself away if it can be helped—especially with the Widow Bray on the premises, as she lately is on Mondays, helping Father with his books—and it can always be helped.

“Well,” the swaying other says, concealing something behind her back, “this isn’t from England. I found it lately on a walk. I thought of you when I unpacked it this morning. Close your eyes.”

Why are her lids closing? Perhaps she’s sleepwalking again, as she did as a child. The girl lifts Clara’s two hands, her two cold hands, and it seems they will crumble and collapse to dust, for she is rarely touched. No servant cinches her into a corset or brushes her hair with the rough strokes of girlhood. Clara wears antique dresses from her mother’s trunk, the empire cut that doesn’t beg support—for why bind herself to sit alone? She brushes her own hair now. It helps the time pass.

“Now, don’t look,” the girl cautions, and how to bear it, both the waiting and the willingness to wait? Clara trembles, cannot but tremble as the plump hands set into her bony ones a perfect brittle oriole’s nest, delicately knit, smelling of the three seasons it has accumulated like shiny coins. Though she’s been peeking through slits anyway, Clara opens her eyes.

“I thought of you.” The girl motions toward drawings marking every free space on the walls, table, shelves.

Is Maggie Fox so guileless as that?

“I like it because there’s a girl’s hair ribbon stitched in.”

Whatever can she want?

“See there, a bit of red? It’s faded now, but you can still make it out. It might be mine. I rather think it is mine—”

Clara winces back tears. No. She won’t weep, not this far from caring. There’s no route out, no safe passage. She manages to mutter a thank-you and sets the nest on her little table heaped with books and sketches. It instantly belongs there as if it never was anywhere else, never nestled eggs at its soft heart or rocked in a cruel wind. Perfectly formed and petrified. This room does that.

Clara nods dumbly, remembering Will’s tale of his mentor, the limber old gypsy, “seller of nesties” at Smithfield. She hears for an instant, and with a clarity she had thought gone, Will’s teasing voice.

“You’re welcome.” Maggie Fox has the sense to leave then, but the door doesn’t click shut just yet. She opens it a crack and lays her words in cautiously, as Will once hurled meat to the lions in the Tower. “They all say you’re mad, you know.”

Of course she knows. On some level, they’ve whispered it since she was born: Poor wretch stopped the world on her way in, killing her own mother. Wise early to the benefits of bed rest and solitude, Clara didn’t discourage them. Being a sickly, boyish, and “artistic” child was her best revenge against a meddlesome world. The “mad,” in her estimation, are routinely treated to the spectacle of people in all their plainness. Like children, they rate human pettiness, cruelty, and longing in the extreme, which, if you’re idly curious about human nature, makes for interesting study. Besides which, it is no one’s business whom she killed or did not kill.

“Why don’t you set them right?”

Already Clara has forgotten who’s speaking, whom she’s speaking to. Her head is full of other times and, faintly, other voices. Once a sneering suitor, complaining to the aunts, called her otherworldly. Ridiculous, of course, since where else would she be but here in the world, waiting, in the cage of her own body?

Clara dabs at the nest with her finger to assure herself that it’s real. “I have no wish to be right.” She plucks a bit of down from the straw bowl and presses it, wiry-soft, to her cheek.

She catches sight of a grinning eye and one corner of the girl’s mouth before the door clicks shut: “They say a lot of things about me, too.”

Father brings tea when Clara rings her bell. She’s taxed. He must know it, for he sits by without a word. She takes up her book, nodding thanks while he pours with tremulous hands.

Before the Widow Bray took to detaining him five days out of seven, this was a routine well established. Clara hardly remembers when it began. When they first settled in New York, it was difficult to speak, to dodge the anger—hers, hard as a bitter blade—reawakened by gossips in Philadelphia.

But Father’s a deal more patient than most. He’s like an old tree, and they value each other, so they staged a truce, even in the face of hardship.

Their conversations now sound the same. “Won’t you take your health outside?” “I won’t today, thank you.” Murmurs of appreciation for the buttery touch of twilight on the east wall or the corner carpet where the feral cat sleeps. Polite protestations about the weather or the sensationalism of certain journalists bent on running stories about boys falling into vats of molasses where they’re promptly licked to death by hogs. This talk is diverting without cost, and less dishonest than their forays into progressive or political subjects—Universalist doctrine, temperance reform. Father would rather enjoy these at ease over a pipe with his companions. She would rather avoid significance altogether, since the one significant thing she might say or ask would destroy their fragile peace with a stroke.

After Will came between them, they learned to be together but separate, to sit and read or sketch or be lost in thought, and to this day her gratitude knows no bounds. Not a bold man, Father has devoted his life to sheltering her, and she, too, shelters him.

Clara won’t admit it to Maggie, but she does prefer the drapes open. She can occupy herself at the window for hours. To starved senses, the back garden is better than a magic-lantern show: oak leaves languid and falling, glossy crows heavy on branches, bats wheeling and snapping at dusk. She can almost recall what it feels like to be out among them where the Genesee winds blow hard.

The natural world she loves above all else goes on working its endless circles, full of phantoms and scurrying small things that keep out of sight to survive, as she does. Larger things, too: the gray fox leaping over an ice crust, the “devil cat”—at least in legend—with its woman’s shriek. Their house borders the edge of the city, and these and more are all alive in her head.

When they first came to the States, to Philadelphia, they learned quickly that it wasn’t far enough from London. The relative wilds of western New York, on the other hand, might be another universe. Whatever healing she’s managed to do she did here, in the gardens, on woodland paths, in the meadows around Rochester.

When Will’s voice did not go from her head and couldn’t be unraveled from the wild world he knew so well, that world began to seem for the first time unwelcoming, and she unworthy. It’s ever what it was, beautiful and shining and full of wonder, but the more she dishonors it, denying what it will have from all who care—curiosity and the body’s cooperative engagement—the more unworthy she becomes, and the more conscious of failure. Sometimes she feels she is nothing now but consciousness, unmoving in her chair, tracking the ever-changing light, the astonishing clouds flying past, the fat fly that circled and circled inside the shade of her reading lamp, knocking like a drunken fool at her thoughts. She forgets she has a body, and when she remembers, grief rests like lead on her chest, in which her heart still beats in its old frame, stubborn as rain. Sometimes she traces her lips absently with her fingertips, marveling at their softness, like the inside of a lamb’s ear, and is struck by the great waste she’s made of an earthly life. But apologize?

Before this room swallowed her whole, she did her best to make do in the world, on ships and trains, in drawing rooms and corsets, lecture halls and tearooms, but the conversations there failed to rouse her, and she felt that she was sleeping through them, dreaming in their midst. Even the best exceptions, the moments that stood out, could never match the joy she had felt in a single furtive afternoon with Will or lying on a hill of heather alone with a dog circling her feet. It isn’t right to hold them, everyone, by his light or against the bee-loud quiet of a grove of trees twisted and heavy with fruit. But she never understood why not. She neglected no vows. She’s taken none.

There’s something about Maggie Fox that teases and troubles her. She can’t reel back the way she can with others, whose faint concern, even tenderness—vulgar curiosity certainly—are of no use to her. Clara doesn’t require friendship. She’s a grateful recluse and believes that many others feel this way but without courage to act on it. Half the women she knew in London suffered “sick headaches” on command, usually when faced with intolerable social tasks, and those with the prerogative of wealth relinquished their children to the household.

But this Maggie Fox has wares for barter, though Clara is too skeptical and sensible to believe. It’s a lovely hoax, of course. The continuity of life. It has the farmers whispering across their fields from Newark to Rochester and the ladies in their drawing rooms too. Clara reaches out for the bird’s nest. It might be mine, for all I know.

Maggie Fox, unexceptional farm girl, has pinned her to a board, recalled her to the human race, enslaved her anew with longing.