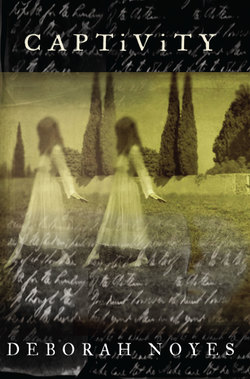

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

9 Pixie-Led

ОглавлениеApril 1835

London

The beast keeper murmurs something to the parrot on his shoulder and thumps his own chest with a fist.

“Be still, my heart.” The bird’s tone is smug and oddly soulful, a world-weary old man’s. “Squawk! Still.”

From a corner of her eye, Clara watches it nuzzle the keeper’s ear, as if in caress. She does not lift her head nor stop her hand, charcoal racing over the ivory page, though she wants nothing more than to look at him straight on, has been wishing it for days since first she glimpsed his comings and goings with shovel and pail in the big circular hall. She longs to memorize the outline of him, work her way in from the shadowy edges with a bit of color, breathe him back on the page through her restless right hand.

But he might catch her at it, and with sketches due for Sir Lever’s approval Friday, it won’t do to digress. Clara settles instead on the young man’s portable shoulder ornament.

Usually the parrot is caged in the aviary in the other building, where it taunts more majestic inmates—golden eagle, griffon vulture, secretary bird, none of whom Clara has sketched yet. If the bird’s comely perch sets it down, Clara will know where to find it.

Father is off in search of this boy’s employer, Mr. Cops, a family friend who has given Father and his assistant—Clara, that is—leave to stay on at the menagerie after public hours. They come almost every afternoon, but Father never seems to note the young man at work with shovel and rake, spreading fresh shavings; sneezing as he hurls hay bales here or there; and sometimes, to her well-concealed dismay, disappearing through the door of the keepers’ apartments. Like the animals, which are ever hopeful of a scrap of meat or a snatch of song, Clara can sense where he is at any given moment.

Unless the public—prone to hanging on the lead gates, hooting at the inmates and disturbing the garrisons—clamors for the spectacle of meat flung to the carnivores, Clara remains in the hollow aisles into evening, sketching by gaslight while Father loiters in Mr. Cops’s library. Locks clanging, the keeper moves among those beasts that will not maim him. Gruff and tender, he barks, “Shove off, fool, if you want a chop” and other husky endearments. If they are favorites, he coos to them.

Motherless Clara has aunts who live to parade her before men of a certain status. Mostly they watch in mounting despair as she neglects them. But Clara’s virtue is a commodity, prized, so where are her guardians now? His voice, so easy and present, seems dangerously close at hand. At times it might be echoing inside her.

They banter back and forth, bird and boy. (Not a boy, exactly—older than she perhaps, but with an air of play about him.) The phrase ricochets on stone, dazzling her with indirection. Once she catches him regarding her with those eyes—a shocking blue, they are—and not regarding her too, as servants do and don’t regard their betters. He can absent himself. He has that gift, it seems, which explains Father’s willingness to abandon his socially vulnerable daughter in the dank recesses of a house of beasts with a loping boy-stranger. Father does not see the beast keeper any more than he takes note of individual beasts.

Besides which, Clara is notoriously sensible. This and her skill as an artist give her a degree of domestic liberty little duplicated in other households. Their first day at the menagerie, for her sake, Mr. Cops made a great show of the leopard’s predilection for seizing and destroying parasols, muffs, and hats almost before the astonished visitor knew to miss them. Father only smiled, well assured. His Clara would not flaunt her finery before a leopard.

But here she is, left feeble-minded by the lean curve of a boy’s back. She’s a honey hive full of bees, all distraction. They have no history, she and this boy, no memory in common, but—and this is ridiculous—she seems to recognize him. His voice, ringing from all directions and none at all, soothes and bewilders, and she envies the bobbing, mangy bird balanced on the plane of his shoulder, gnawing his ear.

Clara won’t lift her eyes from her charcoal sketch but uses deft knuckles and thumb to smudge, deepen, enrage the white space. It’s spiteful, the ivory page, sworn to see her fail. But caring little lets her succeed where her father, who in his quiet way cares so much, fails. She sometimes imagines her talents come of a spell cast by some benevolent spirit on behalf of her dead mother.

Clara draws as well as any scientific artist in London, and the older and more marriageable she becomes, the better she understands: this is her breath and barter.

He’ll be in this gallery, Clara knows, for at least an hour. It’s evening mealtime, and now she knows his habits as she knows those of the other residents of the menagerie, of which there are fewer and fewer each day, with the king and Cops gradually surrendering them to the Zoological Society of London’s more scientific venture at Regent’s Park.

The cats will pace and sleep at intervals and then crowd with tensing muscles by the slat door a quarter hour before their meat arrives. Old Martin the grizzly makes three long paces and then rubs his back against the stone and, turning, flings his upper half into the air before beginning the pattern all over again. She knows when the singing birds will sing, if at all. The hyena and a gaunt American black bear share a den, and while neither actually succeeds in killing the other, relations between roommates are daily tested. When they have a bone to squabble over, squabble they do, in a ludicrous manner, and the devious hyena always wins the day.

“Which of my lovelies are you drawing today?” His voice seems almost shy, though she knows a glamour when she meets one. She doesn’t make the mistake of looking at him.

But it’s a bold gesture. They’re alone and he at least remotely in the Crown’s employ; he couldn’t know who she is: the daughter of a great man? An old friend of the royal line? A courtier’s child? Her clothes are plain but fine, the product of doting aunts who pity her prospects. He can’t know whom he might offend, or that she is only her father’s daughter, here because her talents have proven useful. Thanks to the charitable impulses of Sir Artemus Lever, an old family friend, she and Father have secured between them a major commission. Father has redemption and she respite from the tedious topic of matrimony.

“I’m sketching that one.” She motions to his parrot. “Since you’ve been so kind as to display him for me.”

He smiles, and his teeth are gently crooked. “Display is a fine word for old Mettle.” He breathes deep and begins a litany that dizzies her. “Psittacus erithacus erithacus, native to Africa. He’s a fine mimic, easily bored, with a tendency to growl, except at me. He’s a vocabulary to rival most men and fancies himself a humorist. Marie Antoinette had a grey like this. So did Henry VIII, one as ill-mannered as his master. That one amused himself by crying out by the river, ‘I’m drowning! He fell in the Thames!’ Or he’d hail the boatmen over from Hampton Court Palace. Across they’d row thinking to be paid for their trouble, but inciting royal chaos was all in a day’s entertainment for the rogue. Mettle’s vain about his dress, drab though it is, so your favor’s a great conquest.”

Clara steels herself to look at him. “Is that the speech you give everyone? Psittacus erithacus erithacus?”

“You’re not impressed, then?” He feigns disappointment. “With the Latin, at least?”

Her lips purse and her nose twitches. It isn’t right. It won’t do. What would Aunt Lucretia advise in such a crisis? Defy flattery. Pray for grace.

She prays but finds him closer. He’s loped closer, and she can see now that he has a slight limp, so slight as to go almost unnoticed, and she can’t breathe. Clara drops her charcoal, and the crayon rolls off down the stone, right to him. Mesmerized. Even a dumb piece of coal knows what to do. But instead—to spare her complexion, as the advice columns trumpet—she practices self-restraint. She feels his furtive gaze, unbearably lit from behind with a hard light, slipping from her face to her hand. Slipping.

“I’d hoped for a nod, at least, from an educated specimen like yourself.”

She looks up and catches him teasing his lower lip with his top teeth to check his smile. “All right, yes.” She lets her breath out. “I was impressed.” Now you’ve done it. “Very.”

He reaches down for the charcoal but doesn’t close the space between them to deliver it, folding it circumspectly in his fist. “‘Very’ because I’m a mere beast keeper and a buffoon, probably, or because the facts were of use to you?” His gaze, now unabashed—and it’s as if she’s never been looked at before this moment, really looked at by another human soul in all her endless nineteen years—is terrible in its brightness, his eyes endearingly ringed round with sun and laugh lines. It hurts, she thinks, hurts, for it does, sweetly, to be seen, and who could have warned her? “I don’t look for charity, as a rule, but I like to be of use.”

She watches him swallow, noting the shadow on his hard jaw—no elaborate mustaches for him—watches him await her verdict. The Adam’s apple travels in his fine-muscled throat, such a lovely sun-kissed throat the color of honey, and for one agonizing instant she’s not in the stony heart of her nation’s capital but lying with this wildly beautiful, clever but no less inappropriate boy in a fall orchard full of goldenrod and smashed fruit and drunken bees, her favorite sort of place. A paler bit of flesh winks under the collar, and perhaps he feels her eyes on it, for he shifts a bit, pulls his cap down lightly, and this is a relief since it shadows those eyes so like the sky over an orchard on a clear day with the white clouds billowing by fast and senseless as dreams, and she can’t look away on her own.

Though he seems frank and foolish as a child, he compliments her somehow, without a word. He makes words redundant. Lord knows words have her in a thicket now.

Mere. Beast. Buffoon. Very.

“A little of both, I confess, sir. But I thank you for your knowledge. My father’s illustrating a scientific catalog,” she adds quickly, to justify her gratitude, “and I assist. He and his sponsor hope to expand their findings into a book.”

“Looks to me that you’re illustrating it.” He smiles with his eyes alone—fearful witchcraft. “I say so humbly, of course, with all respect due your father.”

“You have no obligation to respect him … a stranger.” She busies her hands, packing.

The keeper clears his throat, motioning gravely toward her sketch. “Mettle will fault me if you don’t finish his portrait.” He glances round and speaks furtively into his curved hand. “He’s vain as any courtier.” The keeper reaches out an arm, and the bird sidesteps up it. “Here, Mettle. Stay or face my wrath. Perch.” He unloads Mettle onto the back of her chair. “Too close for you?”

Isn’t it? He draws back the dirty, strong-veined hand, but “No,” she says. No.

He motions toward the relative quiet of the semicircular exhibit hall, where animals in their cages snuffle and shift, warm bodies settling not in content or resignation but some other rhythm they understand, which all captive creatures understand. “Work’s a solace, ain’t it?”

He doesn’t wink before he goes—that would be impertinent, even for a beast keeper with no grasp of English grammar—but he does reach out almost sadly for her hand and close the charcoal in it. You might suppose they’ve known each other for years and none would think the worse of it. The warmth of him causes a riot in her skin, though his voice calms it again, and in her mind she’s pleading, No, but he lets go, and she breathes him out, and the beast keeper goes his merry way, humming and speaking softly to his charges.