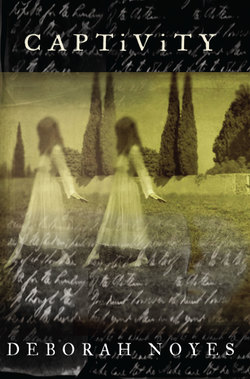

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1 Machinations

Оглавлениеmarch 31, 1848

Rochester, new York

A bell is tolling for me, Clara thinks, awakened in her chair by the wind. Or in spite of me. For weeks now she’s listened into the creaking strangeness of the old house she shares with her father, a roused house. She’s tracked footfalls and merry whispering behind closed doors. But tonight, in the clamor of dusting and meddling downstairs, she hears at last the death of something. She understands that to be as she was before—to barely be—will not be tolerated.

The same rude wind that seized her curtain with a snap, startling her awake, holds her at the window. She rests her forearms on the sill, her nose twitching like a fox’s. Out there, all is bluster and agitation. Flailing laundry haunts the lines, and if carriages are arriving round front, she can’t hear them for the wind; beyond alley rows and back gardens, it propels anything light and loose along the roadways. Ash-can covers clank, and a raccoon makes its furtive, clumsy way down the neighbors’ rain vent. Clara watches with delight as the animal shimmies, curling like a flag at low mast before lighting on its haunches in Matilda Frye’s winter garden. Then it pads out of sight into the outer wilds of Rochester.

It was unseasonably warm earlier, almost sultry, so she let the fire die, opened her bedroom windows, and drowsed in her chair, soothed by the good smells of river and thawing mud. She forgot for a time the mean truth: that the parlor downstairs will soon be full of strangers.

Father has broken their pact. He’s betrayed her to that Widow Bray, who now “advises” him on domestic matters, it seems, though Clara has managed to run their modest household these twenty years past. Worse, by requesting her presence at his gathering, he has forced Clara to refuse. He has made his grown daughter publicly defy him, an agony for both.

Delicacy is not the widow’s strong suit.

Clara wouldn’t begrudge her father a companion, a helpmeet, but let him steer that helpmeet—machinations and all—away from her. Isn’t that understood? Clara’s never had with maids underfoot, and Father eats at his club; no need for a cook. In fact, since the unpleasantness in Philadelphia, they haven’t hired in at all.

How then is this house, Clara’s only refuge, lately, incredibly, crawling with strangers?

Closing the shutters, she turns her thoughts to horses. If carriages must intrude at the front gate—and by now, they must have—there will be horses. Black and bay, dapple and gray, all the pretty little horses, swinging their glossy manes. But there will also be coachmen setting out carriage steps for ladies in ringlets and hoops and shawls. Doors will open and close, and open.

And they do.

Little by little, the lower story fills with voices.

Clara knows how sound inhabits every room of this house. She knows what board squeaking signifies what stance and where her father is at any given moment and whether he’s in boots or slippers. Her ears are like spies and travel out, fan out an army and return with intelligence.

But this is cacophony.

Clara smooths the folds of her wrinkled morning gown and slips out into the upstairs hall, easing the door closed behind her.

She moves slowly at first, calmly, until her hip bumps a table, knocking some knickknack to the carpet, and she spooks like a horse in a narrow stall. Her bare toes curl in defense, but she doesn’t pause. Her hands trail over oval frames and carved wainscoting.

If she could she would stop the voices, the laughter, rising round her like bars. Her breath is feathery, her life a crushed bird. Who are these people? Who’s playing the square piano—unplayed all these years? Who thought to tune it and unseat the dust? Not Father.

Why has he exposed her this way? He owes Clara her privacy, and more. What else does she have? What more could she want? To die, maybe, or live. To leave the place between.

For nearly two decades, her entire adult life, the place between has served. It has been Clara’s habit and shelter, her home, and now it’s under siege by progressive ladies in clip bonnets and cross-barred silk. She knows the crowd well enough, if secondhand; to keep his recluse up on the world’s passing, Father gives regular updates on the doings in his social circle. Clutching the banister, Clara listens, but she can’t distinguish voices in the cheerful din or find her father’s. He speaks so softly.

As if she might yet descend and make her entrance, Clara smooths her simple skirts—no hoops for her, no boning, no bother—and plunks down on the top step. She lurks long in that dim stairwell in a gown the same tired shade as the marmalade cat (a feral tom who sometimes graces them … like her, he’s found himself exiled upstairs) now purring and stabbing his front paws lustily into her thighs. Wild-haired and bare-footed and with Will at her back—near enough to feel but never near enough—Clara gives the tom the rough strokes he craves. Spotting a dribble of tea on her bodice, she sees herself as her father’s guests might now, given a candle and a chance, as a mad, furtive creature, a truth best hidden.

She cranes into the gaping air, and the dark is dizzying. Strains of conversation emerge, now that the tinkling piano has ceased: someone has been to a thrilling lecture by Margaret Fuller … Seneca and abolitionism … capital punishment … prejudice against the poor and the Irish … asylum conditions and hygiene …

Clara hears her name amid the worthy clamor like a strange bird’s song. Her listening sharpens. That vile woman’s asking after her health again as if Clara is an invalid … perhaps she is, in her way, but would the widow raise that specter in polite company? No. They’ve absconded. Father and his Mrs. Bray are out in the hall now, hovering between the drawing room and Clara’s realm above. She sees the widow, or her reflection, in the glass of a heavy walnut hall stand heaped with coats and top hats on pegs. One gloved hand grazes the multitude of umbrellas in the stand as if to assess their quality.

“Your daughter has so much to offer.” The voice drops to treacherous, flirtatious. “As you yourself attest. Why let her live like a recluse?”

Clara can scarce make out the words now. She has to strain and imagines how her face, poised between the banister bars, would appear from below. An apparition. Were they not so absorbed in each other, they might sense her up there spying, but they don’t; they won’t, Clara knows. For one with so little social care or opportunity, she’s learned to read people precisely.

Father remains out of view, but the widow—or her reflection—moves in accord with him, speaking with her hands. “I know a capable physician….”

Does he love her? Say he’s invited Mrs. Bray and the others here to announce his intentions. What then? Submitting to the will of a busy housemistress (someone like Aunt Alice, perhaps, who lived with them throughout Clara’s youth in London—a woman with bold opinions about how Mr. Gill’s dependents ought conduct themselves) is beyond humiliating at Clara’s age, even if her temperament allowed.

“… a gentleman who attends nervous conditions … sensitive to the artistic, in women especially …”

“One doesn’t ‘allow’ Clara anything….” Father laughs uneasily. “Goodness.”

Well that he remembers how to speak, how to salvage for his child the smallest dignity.

But the widow’s intent is obvious, monstrous. “You’ve sheltered her well, sir. It does you much credit and your daughter no good.” The hand in the mirror reaches. “Now, then. Who heads this household?” Clara has a glimpse of trimmed whisker as he tilts his head to receive her caress, all obedience. “Let us go together and fetch her.”

Clara stiffens, and the disapproving cat leaves a chill. The upper hall is full of shadows that she, like the rangy tom, might dissolve into.

As the widow in the looking glass peels off a glove, Father appears in the mirror, trying almost playfully to detain her. Instead, she steps out into full view. Striding the length of the hallway below, she runs her plump hand, loosed and creamy, over framed rows of zoological drawings: Clara’s.

Sometimes Clara can desert her senses the way the cat did her lap, absent herself from nubby carpet and waxed wood of banisters and chiming clocks. But however expert her stillness, they’ll spot her and say (sternly), What are you doing out here? What do you want? As if they hadn’t set out to find and disturb her. As if they were not in the least responsible.

“She’s in frail health,” Father says with such grave patience that Clara loves him again.

The widow considers, accepting the lie as she might a satisfactory bolt of fabric from her dressmaker. Father scoops her glove from the floor, she accepts his arm, and they return to their noisy party.

Mine, Clara thinks. This is mine. But a peal of laughter behind the drawing-room doors rebukes her. Tell me again, Will, she pleads. Why have they come? All these strangers?

Clara listens for an answer.

Clara listens.