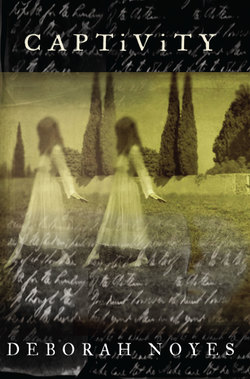

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

7 In the Fever of Not Trying

ОглавлениеIt’s said these girls can communicate with the dead. How to reconcile Father’s blunt words with the ridiculous monologue ensuing downstairs in the drawing room?

With her closet door open, Clara hears the whole thing through the dumbwaiter shaft: the widow braying like a tiresome donkey, like the wife she isn’t yet, like the busybody she’s doubtless always been. Shall it be a Tuesday/Thursday schedule for Miss Lizzie and a Monday/Wednesday/Friday for the other—Margaretta, presumably, though the elder, Leah Fish, has yet to confirm which of her two younger sisters she’ll farm out for labor and which she’ll keep at home—and will you have them for three hours each day or four? And would it be better to include one weekend day, and if so, Saturday baking day would be better, would it not? And do you take an ample afternoon tea and a light high tea, or the reverse? Surely you won’t subsist on bread-and-butter sandwiches for the former … perhaps some more inventive recipes? Chicken curry? Cucumber mint? Radish-poppy seed?

If sound and silence be indicators, Father is winningly defiant, pausing between questions and sometimes not responding at all, at least not that Clara can hear. Nodding, no doubt—or nodding off—over his news sheet as the widow prattles on in her grievous, well-meaning way. Clara can only hope good Mrs. Bray drives him past his point of no return, an arduous if not unreachable destination. Clara, meanwhile, is a ghost in her own home, neither awake nor asleep, aware of her own transparency.

There will be plans galore, more and grander plans, and the endless, tedious discussions that go with them, discussions she will be expected to partake of. The widow’s voice will echo round the walls, tomorrow and again and the next day and the next, seething with intent, and then will come other voices, servants and strangers, each with her will, her agenda, her own wills and won’ts. Those same walls seem to be pressing in on Clara, inching closer. The inevitable beats on them with blunt fists, and she can’t devise a way out or a defense from within.

The light is failing. Heavy-lidded, she wakes and sleeps and wakes again. Once this pattern was as peaceful as a lapping tide; now it rises and falls like floodwater, all damp chill and promised destruction. What will she wake up to? There is a continual sense of things changing, disassembling, reassembling outside her view. If only she could glimpse that stubborn future now, once and for all, and know the degree of the problem.

All is eerie silence when next she wakes. It seems moments ago the question of To Radish-Poppy Seed or Not to Radish-Poppy Seed ruled the world. Now stillness blankets everything, and Father’s curious words fall softly there, like snow: It’s said … it’s said … the dead.

Who says they can do it? Who claims this knack for them?

Idiots? Fools? No. Amy and Isaac Post are not fools. Nor are the others in Father’s circle, even the more credulous among them, like the Widow Bray. Overhopeful, perhaps—unlike his friends in London who would laugh such claim into submission—but not fools. America is full of sunny, hopeful people, despite all evidence to the contrary—but are hope and folly necessarily the same thing?

Clara opens a window, breathing hard, closes it again. She is a vile, dependent thing, and not since London has this rude certainty been more present; she has no place to go once Father abandons her to the wolves of domesticity and society, and no one to go there with. For years Clara has been allowed to be indolent, inviolate, hidden. She’s needed and longed for nothing, and nothing has been expected of her.

If she could see far enough into the future to know what the widow will make of her life, Clara might find cause to end that life quietly, gratefully, taking the only initiative she has left. But she can’t see. She doesn’t know, and she is frightened and angry for it.

To ease her panic, she fumbles for sketchbook and pencils. Tonight she peers down into the well where her heart still lives in search of a story. As a rule, the past repels her, but the best stories belong to childhood, and her best to Artemus and Mary.

Artemus favored the classical, the Greeks and Romans. Mary drew on changelings and other fairy mischief. To honor them both, Clara fishes from her dark well the myth of Proteus the sea god; to elude captors who would have him tell their future, Proteus shifted shape.

Clara sometimes tires of drawing animals, but for better or worse they’re her subject of record, and every picture, every story commands them. Her pencil begins, then, with a wild eye, a wing and a claw, with flashing fur and diamond scales. She sketches furiously as wily Proteus takes many forms, but she outlasts him, and at length he must assume his right form and gift her with her future. And so appears, like a wolf loping out of a fog, a man’s face. Not the gnarled old sea god—eyes sunk in their webs of flesh, the stained ivory of a foot-long beard—but a beloved face unfurling against her will, frightening for its likeness. Did she trust she had forgotten?

There is William Cross, unprecedented on the page and unwelcome, unapologetic. The eyes, truer than any human eyes she has ever fashioned, even in the fever of not-trying, stare back at her, noncommittal but intense, as if he isn’t certain how he got there or what to make of her. And could he be? Would he know her now? He’s an agony and an outrage: beautiful, young, unchanged—and she a puffy wretch of questionable appearance (when did Clara last consult a mirror? Vanity is the first to die, followed by curiosity, and hers left her years ago). She slaps the sketchbook closed.

Do you frighten yourself? For a moment she applauds her own skill, though it feels less like craft or genius now than some reckless imposition. She has sketched Will—or her memory of him—from every possible angle year after year and never found a likeness, quite, and never tired of trying. She’s concocted him hair by hair and heartbeat by heartbeat, over and over, that ceaseless task of unrequited lovers, grieving mothers, fathers of sons who commit unspeakable acts, abandoned children. Will is a locked door for which there is no key, and he can neither satisfy nor disappoint.

In the spirit of foolishness, why not take up that bit of tripe father has left on her side chair, a penny-press account of the haunted doings in Hydesville? A hook for a dull fish.

Clara reads intently, her brow furrowing. What would her old friend Marianne Pratt conclude? Is this why Galileo faced the Inquisition and died a prisoner, or Diderot labored over his encyclopedia? Why Wollstonecraft dissected Malleus? So that a pair of farm girls might arouse ancient superstitions in a credulous public?

Father left the pamphlet conveniently by because he wants to engage with her on this point, clearly—his strategy whenever a new book arrives or a lecture incites enough controversy to be written up in the morning papers. So many of Father’s influential friends have been taken in by this spirit ruse that Clara has to give him, give all of them, the benefit of the doubt. She reads through to the end, sits a long moment, and feeds the pamphlet to the fire, transfixed by the leaping flame.

Rousing herself, she takes up her sketchbook and thumbs through to Proteus transforming, shifting closer to the truth. How often has she spoken the words in mind: Tell me, Will. Tell me? What would he tell her, if he could?

She pries the page from the book and systematically begins shredding the deathless lips, the sad, scarred sweetness of expression, until only his accusing eyes remain. These she tears also, first one and then the other, flinging him toward the ceiling, letting the confetti of Will Cross rain down on her feet and her furniture.

Here’s a mess for you, Clara thinks.

Let that silly girl clean this. Give her real work to do. Let her fall on her knees in vain. Let her see that neither prayer nor wish nor trickery makes it so.

The dead are silent.

The dead are gone.