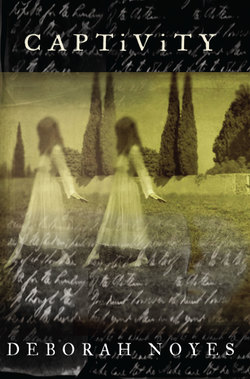

Читать книгу Captivity - Deborah Noyes - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

2 Mr. Splitfoot, Do As I Do

ОглавлениеHydesville, ny—the same night

Here is how the Fox sisters teach the dead to speak.

Maggie and Kate are giddy with fear on the mattress when Ma comes running with the candle. “We’ve found it out,” they cry, and Ma’s monstrous, flickering shadow rounds the bedroom wall. She nods hard, poor soul, hefting the candle higher, and her hand shakes.

“It” is the rapping that’s robbed them of sleep and peace for so long, a hellish business, and who can bear it? Not Ma, surely.

She’ll have to, thinks Maggie, who is filled with fate as a sail is for going. Yes, they’ll go, she understands, from Wayne County with its brittle fields and trees—an unrelenting patchwork of brown and white to which spring takes its sweet time coming—and it won’t be long. Even Ma’s weary, pious face can’t prevent it.

As if reading Maggie’s thoughts, her younger sister, Kate, springs out of bed and snaps babyish fingers. “Follow me,” she orders, and how can Maggie not? Who can take their eyes off Katie Dear, so like a blithe spirit herself, all hush and mischief in her threadbare shift? Snap snap, and then, in the shadow of Kate’s trailing hand, rap rap, audible as a heartbeat, deep inside the house.

“Here, Mr. Splitfoot.” Kate claps milky hands three times. “Do as I do.”

Rap rap rap.

The phantom makes the very walls quake, it seems.

Beneath the spectral racket, Maggie hears the usual soft sounds of night, the ordinary unease of their little rented saltbox cottage: mice scrabbling in the walls, moaning March wind, creaking cold floorboards. These were lonely sounds before and chilled her, but now and suddenly she misses them. Almost. Their empty promises.

She watches the shadow-flicker of branches dreamily. They’ve not been in the cottage—meant to serve till Pa gets the new farmstead built—long enough to inhabit it, really. Ma hasn’t hung their few gilt-framed pictures. The walls, paperless and water-stained, are bare but for the cameo of Grandmother Rutan over the washstand.

Maggie would sooner leave “Mr. Splitfoot” out of it. Already, in just these few days’ time, she finds it hard to unravel the sounds she makes or imagines from those without—from her sister, from the earth or the air. It’s like when you’re rapt with your chores and hear a voice humming but only later, an instant later or an hour, recognize your own voice. Now’s no time for the Devil to come calling.

“Three raps mean yes.” Kate’s voice rings like a rifle shot, and Ma might be a mouse caught in the flour barrel for all her astonishment. Even dour Father has been reeled in now, the hand scarred with old burns from the forge supporting his weight in the doorway, his eyes unreadable behind a candle-glare of spectacles. Yes, our ghost is still here. Did you really think he’d go so easily?

Maggie can’t but take a certain pride in having disarmed the man who’s so cheerlessly charted their collective course. Until tonight.

Rap rap rap.

They are all wild-eyed for lack of rest. Should Maggie scold Kate or applaud her—treacherous girl—for taking it this far? Too far. Her sister won’t meet her gaze. They have no plans. They know no allegiance in this game, if indeed it is a game, and now for once Maggie’s unwilling to say that it is or isn’t, to ask it, to know. But it’s theirs, whatever it is, and Kate’s sport is catching.

“Now do as I do!” Maggie waves her arms, signaling three times like a mighty hawk flapping phantom wings or a hell-bent angel. Her winged shadow swells, shivering inside the black dance of branches on walls and wardrobe and the graying old quilt Ma spent a whole season of evenings squinting over by the hearth, stitching and squinting.

Rap rap rap, replies the ghost.

“It can see as well as hear!” she exults, but Ma hears only their visitor now. Maggie looks to Kate, smiling with her eyes like Mona Lisa. Kate does not look back, but Maggie smiles anyway. Their ghost commands what they cannot.

“Are you a disembodied spirit?” Ma sways in the balance. “Speak now! I’m so broken of my rest I’m almost sick.”

Rap rap rap.

“Tell me my eldest child’s age.”

A torrent of rapping, on and on till Maggie loses the will to count. First for Leah, and then Elizabeth, Marie, David. Her mind wanders through the storm of noise, a steady thumping as of some giant come to tread their roof, but Ma is breathless, vigilant, counting along. Fifteen raps for Maggie. Eleven for Kate.

“My youngest now,” Ma demands mysteriously, and Maggie thinks, It’s one patient ghost to weather such a taskmaster. Besides which Kate is their youngest. But the visitor raps thrice, faintly, and Ma swoons. So there was another child once. Did Kate know? Why not Maggie? Father’s lips flap in prayer, and Maggie wonders at the secret, mortifying world of adults. What more unspoken? What else?

“Will you continue to rap if I call my neighbors in?” Ma trembles. It’s a terror to see her this way. And a thrill beyond reckoning. Pity and fear catch like a bone in Maggie’s throat, but she has no shame, evidently. It’s too late for that.

“That they might hear it also?” Ma pleads.

Maggie imagines the men and boys out night fishing by Mud Creek. They’ll mill and murmur with eyes full of moonshine. They’ll listen intently, blow into strong hands with icy breath. She will have them in thrall.

Rap rap rap.

Ma stamps out into the darkness of the hall, clutching her shift close round a spacious bosom, Pa stumbling at her heels.

Kate leads their visitor up and back in a hypnotic square, the walls resounding. Doesn’t she see there’s no one left to impress now? Where has she gone to in mind? Her eyes shine like ice.

Rap. Rap. Rap.

Had the river burst its banks and come swirling in under their roof this night, Maggie understands, the Fox sisters could not have seen their way clear.

We were born for this, she thinks.

The first to arrive is candid Mrs. Redfield, meaning to have a laugh at their expense. Indulged city children (the Fox family has only just relocated from Rochester) scared silly in their beds.

But when Ma enlists the clever spirit to rap out her neighbor’s age, Mrs. Redfield promptly fetches Mr. Redfield. His ripe old age is likewise disclosed. He, in turn, sends for Mr. and Mrs. Duesler, who summon the Hydes. Before the girls know it (always “the girls,” as if deprived at birth of Christian names), the house swarms with eager Methodists in various degrees of undress demanding audience with the spirit. For shame! Ankles on view everywhere, even the ladies’, and this is something. This is grandeur.

“Is it a human being that answers us?” prompts Duesler in his righteous baritone. His morning beard shadows a doughy jaw. His bare feet with their revolting horny nails—he alone politely removed snow-crusted boots at the door, woolens or no—rivet Maggie. The only sound in the now overheated room is squeaking-wet soles. The occasional dry cough. “Is it a spirit? If it is, make three raps please.”

Rap rap rap.

“Are you an injured spirit, then? Make three raps if you are.”

It does, and it’s deafening.

“Were you injured in this house?”

Yes.

“Were you murdered?”

Yes.

“Can your murderer be brought to justice?”

No comment.

“Is the person living that harmed you?

Yes.

Everyone in the room seems to shrink, for the only expedient way to finger the assailant is list each luckless person they can think of and hope for a match, which is cause for murmuring and downcast eyes. Who will be named? On what grounds? Who will do the naming—offending whom? With a lofty sigh, their leader, Mr. Duesler, proposes, “There are twenty-six letters in the alphabet. Will you rap out the number that corresponds with each letter? One for ‘A,’ two for ‘B,’ and so on?”

Yes.

With this tedious method, their ghost, identified as a Mr. Charles B. Rosna, formerly an itinerant peddler, narrates its violent demise. Five years earlier, for his worldly wealth of five hundred dollars, his throat was cut with a butcher knife in the east bedroom, his body dragged down through the buttery to the cellar and left lying the night long. In due course, he was buried ten feet below the earthen floor.

The population within the little house, meanwhile, has surged. Men up from the creek move with fishing poles slung over shoulders, a threat to life and limb, though a thoughtful few have lined them up outdoors. Too exhausted to navigate the forest of ripe bodies, excited to the point of collapse by clamor, Maggie prays for sleep under the stairwell crawlspace. She wishes Mr. Hyde would take out his fiddle, that for a change they might roll up the ratty rug and dance as they did in Rochester, instead of milling about rooms where a dead man got dragged, his blood streaking the boards.

When Charles B. Rosna intrudes on her thoughts, her rest under the stair is broken. Maggie crawls out, slapping spiderwebs off her dress, to search for Kate, who’s retreated to the empty room upstairs, their room before the rappings began. Kate is wound tight in a blanket, a dead weight that Maggie can’t unravel; nor can she pry her way in, so she lies alongside her sister’s mummified shape, Kate’s breath soft on her cheek and faintly stale in the sweet way of childhood. Maggie watches her sister’s chest rise and fall and the flicker of her pulse at the hollow of her freckled neck. She buries her head in that warm space under Kate’s chin a moment, marveling at their sway over and invisibility among so vast an assemblage of neighbors.

A low roar of voices fills the house as even the spectral rappings did not.

But the thing in the cellar commands her. Even if she and Kate and their joint imagination have planted it there—and she can’t say for certain anymore—the peddler’s ruined body has swelled, spread like a foul demon vegetable in the nether regions of their farmhouse. Maggie can’t long keep it from her thoughts.

When the rappings began, Marta Weekman, who’s nine but seems younger, told Maggie and Kate matter-of-factly that she once lived in their house and suffered there. It knocked, Marta said, and when her father answered, there was no one. Her pa raced round in bare feet to see was the knocker here concealed or there, and this—her befuddled father’s evident lunacy—terrified her worst of all. One night she felt a hand trail over her sheets as fingers play on water or a harp, and when the hand reached her face, it was cold. She lay rigid till dawn, too stricken to speak or cry out, and refused to enter her room again after dark. Not long after, her family moved out.

Maggie hopes it won’t touch her.

On the other hand, what might it feel like, being touched by a hand from Beyond? Wondering—like when she wonders about God or the devil—makes her feel light and unpinned from her body, wide-awake and willing to a fault.

She curls tight, listening to the swell of voices. Safe among her family and neighbors, Maggie wonders, is Marta Weekman downstairs with her parents? Or have they had their fill of the spook house? She wonders about the rappings, about herself and Kate, whose breath now warms her wrist. All these people milling about in the strangeness of night, including the peddler with limp head dangling over a great gash. Who are we? How have we come to be here? Now. Together.

Maggie lurks outside the parlor next morning, holding her shadow back from the threshold.

Inside, in full morning sun, Mrs. Redfield kneels, surrounded by a hushed assemblage—more arrive every hour—of villagers. She asks in a voice unfamiliar and soft, urgent enough to make a blacksmith blush, “Is there a heaven to attain?”

In broad daylight, the question floats down among the farmhouse congregation like a feather. It rocks on the air like a baby’s cradle. Each word a creaking prayer. Is. There. A heaven. To. Attain.

Right on cue, Mr. Charles B. Rosna arrives with comfort.

Rap. Rap. Rap.

“Is Mary there?” Mrs. Redfield, on her knees, bows her head. Her shoulders shake, but only just. “Is my Mary in heaven?”

However petty Mrs. Redfield is, she deserves an answer. But it was a poor night’s rest, and already Maggie’s weary of the work and the day. She saunters off, trying not to imagine the rueful silence in her wake. Does their bold new world exist when she’s not present? When she and Kate step offstage? Who was it said the world’s but a stage? Mr. Shakespeare. She thinks fondly of Amy Post reading aloud from a leather volume while she and Kate lazed on their stomachs, bicycling back the air with stocking feet, their skirts in an unladylike sprawl. Amy’s a Quaker and can’t approve of the plays, which Maggie’s managed through her own cunning to borrow from her pastor’s library, but Amy makes an exception for the poems.

After that, the spirit is reticent. People come and go, and it doesn’t please them to go. They linger by wagons, stamping with the horses. They murmur into their gloves. Kate is young yet to rate the lash for immodesty, so after they procure a furtive lunch of bread and too-ripe cheese, she climbs the attic ladder to view it all from the rafters.

By evening, men and able boys have commenced digging in the cellar. Debate rages among them and floats up through floorboards.

“We can’t lower this water.”

“I never have seen or heard a thing I can’t account for on reasonable grounds.”

“Account for it, then.”

“I see no human agency at work.”

“Rats. None but rats in the walls.”

“The Fox elders never seen any rats.”

“There’s that cobbler fellow down the way. Might be an insomniac hammering his leather all night.”

“He’s outside now, taking his nips on Obadiah’s wagon while we dig.”

“Waste of a night’s rest.”

“Why does the spirit rap only with those girls present? It’s fine sport for them.”

“These children were the first to befriend it. Maybe it trusts them.”

Maggie wonders if Kate feels the same excitement she does with some two dozen strong-armed men in sweat-stained shirtsleeves laboring just below the floorboards, or is Katie too young for that?

The men dig and dig, metal picks ringing on packed earth, until a great, violent scraping sounds and one man barks, “There! You’ve done it again. Here comes the water racing.”

The men stamp mud up the stairs, their spirits dampened. They emerge singly and in pairs to convene round the kitchen, mutter, and warm their hands with Pa’s coffee.

There is no rapping that night.

Long past bedtime, youngsters sprawl under tables, whispering with ears pressed to the planks. They kneel and play at jacks as big frighten little with grotesque, silent pantomimes of the dead man, heads dangling limp on boyish necks. The house smells of warm cider. Mr. Hyde slyly kisses Mrs. Hyde behind one ear. A dog barks far off, and keeps barking. But gradually, the good neighbors trickle out. Ma leaves the men and the stragglers to it. She steers her girls out after Mrs. Hyde, and the Fox women sleep on a hard bed in strange bedcovers, dreaming of phantoms. They sleep straight through their morning chores.