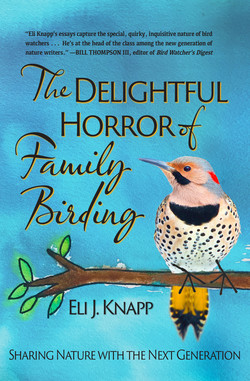

Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSteller’s jay

Cyanocitta stelleri

1 • THE ONLY THINGS TO FEAR

Ah! reader, could you but know the emotions that then agitated my breast!

—John James Audubon

“Kestrels! They’re attacking!” my brother Andrew yelled from his sleeping bag. Three birds had landed on the railing above him, shattering the pre-dawn silence with cacophonous calls.

Andrew and I had spent the night sleeping out on the small deck of my red, ramshackle cabin. Now he was determined to get back inside. Unwilling to shed the pseudo-shield his sleeping bag provided Andrew chose to roll over me in my own sleeping bag, crawl to the door, and lurch inside like a clumsy, overgrown caterpillar. As the door slammed, I heard him collapse on the floor.

I lay still on the deck, watching the birds as a mischievous, Grinchian smile spread across my face. The alleged kestrels were not kestrels at all. They were Steller’s jays. This particular trio had been visiting my cabin’s deck for several months now. Before marriage and grad school, I took a one-year job as an outdoor educator in central California. At night I slept in a closet-sized cabin with a slightly more spacious deck, just big enough for two sleeping bags to lie parallel. Impossibly tall redwood trees amid a carpet of ferns lent a fairytale feel to the forest enveloping the cabin. In my mind, it was a perfect setting for a band of clever, cobalt-colored birds.

But not in Andrew’s mind. It was just after six a.m. The jays had come down with their typical homicidal cries, proclaiming their right to the meager peanut offering I always put out the night before. To Andrew, who lacked prior exposure, it appeared an outright avian assault: dark-crested villains swooping down through the gloaming, hell-bent on snatching souls. Since he’d arrived only the day before, I had forgotten to mention the routine, early morning visit of the obstreperous jays. Together, we’d decided to sleep out on the deck. Serendipitously, he chose a position right by the railing. It was too good a prank to be premeditated. Stellar indeed.

My delight then, as now, spawned from the competitive nature my brothers and I share. Our competitiveness is so intense it spills over into sibling schadenfreude, or pleasure derived from the misfortune of others. Despite being four years younger than me, Andrew is far more academically gifted. He processes information faster, his memory is better, and in most areas where I struggle, he excels effortlessly. So whenever I discover a chink in his impressive armor, I exploit it. The misidentification of a bird accompanied by a hysterical, panic-stricken reaction was a gaping chink, the height of schadenfreude. As the last jay lifted off my railing and the avian apocalypse ended, I knew I had sweet fodder to turn him red-faced for years.

I gained something else from my brother’s misfortune: insight. Though the incident seemed trivial at the time, I learned that Andrew had fears I lacked. I spent the bulk of my youth in the woods. Andrew didn’t; he was an indoors kid. To me, birds were familiar, and I sought them out. Not so for him. He coexisted with them. To him, birds were backdrop, noticed only when they hit the windshield or woke him up.

Andrew wasn’t culpable for his indifference; we merely differed in our formative influences. Nature-oriented friends and teachers dragged me into the fields and forests throughout my childhood. Obviously, kestrels don’t attack sleeping men in redwood forests. But Andrew’s lack of experience, punctuated by an unexpected blitzkrieg of birds, translated into misapprehension and fear.

Now, as a professor, I routinely hear echoes of my brother’s experience in the lives of students enrolled in my ornithology course. Often hesitantly, and without much eye contact, a student admits to having a fear of birds. The first few times this happened, I had to force a deadpan response. Cheerful robins and beautiful bluebirds leapt to mind. How could anyone be scared of these colorful feathered friends that fill the air with joyous melody? “Can you elaborate?” I’d ask, clenching my jaw to prevent a smile. Most of their explanations were vague and ambiguous. But finally, this past spring, I confirmed the suspicion I had gained way back in the redwood forest.

“I’m here because I need to get some science credits and …” Emily said, her voice trailing off.

“And what?” I asked, curious.

“Well, because … I’m scared of birds.” She stared at her desk as her face turned the color of a cardinal. Here we go again, I thought, gripping my podium to squelch any potential flippant reply. The class giggled, and several students smirked at one another.

“So I’m here to get over my fear,” Emily finished. This wasn’t the time for a cross-examination. She had been brave, and I wasn’t going to add any further public humiliation. I moved on to the next student but made a mental note to follow up with her if an opportunity presented itself later on in the course.

“The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt memorably proclaimed back in 1933. Catchy as his words were, Roosevelt could have used a fact-checker. In 1960, for example, researchers Gibson and Walk discovered that humans innately fear falling. Several decades later, another researcher, William Falls, determined that even as babies, we startle at loud noises. Culture has nothing to do with these innate fears, and they’re exceedingly difficult to undo. We learn all our other fears along life’s path, picking them up like odd-shaped pebbles. While lots of people fear snakes, we’re not born that way; we acquire it from our culture and our environment, taking most of our cues from our parents. My wife, Linda, for example, grew up in West Africa. There, many snakes were venomous. She was taught that the only good snake was a dead snake. The opposite was true for me in the friendly snake world of the northeastern United States.

An inveterate collector of flora and fauna, I have shown my son, Ezra, dozens of snakes and bugs ever since his diaper days. And when Linda wasn’t looking, I gave him many to play with. So it came as no surprise one day to find him chasing Linda through the yard as she yelled at him to stop. Confusion was on his face then, while a little green snake dangled from his hands. Why was his mother scared, if his father wasn’t? Even more unsurprisingly, and to Linda’s great consternation, Ezra’s early confusion soon morphed into devilishness as that initial chase evolved into an episodic—and highly cherished—game. Needless to say, I bring home far fewer snakes than I used to. Not that I need to. Now he collects them himself.

Fear can be learned, and it can also be paralyzing. In the 1920s, Walter Bradford Cannon coined “fight or flight” to describe key behaviors that may occur in the context of perceived threat. Although oversimplified, I like the way neuroscientist Seth Norrholm described it. Fear, he wrote, can cause us to take the “low road or the high road.” If the brain’s sensory system detects something to fear, adrenaline kicks in, our hearts beat faster, and we get the classic fight or flight response. Once we journey down this low road, our fight or flight may malfunction, causing us to freeze like the proverbial deer in the headlights.

Recent research suggests, however, that freezing may be adaptive, not a malfunction at all. When fleeing or aggressive responses are likely to be ineffective, freezing may be the best option. Like possums that play dead, we freezers experience “tonic immobility,” which instantly derails our motor and vocal abilities. Judging from the number of times I’ve turned to stone as my two-year-old daughter momentarily chokes on a piece of food, I’m a bona fide freezer. Even though it may be an adaptive response for the possum, it hasn’t seemed so for me, especially as a father with young kids. In the language of Norrholm, I’ve lived on the low road.

If my wife hears our little girl even faintly sputter, however, she will grab the baby, pat her back, and save the day with nary a quickened pulse. My wife may be afraid of snakes, but with choking and innumerable other injuries and accidents, she takes the high road every time. We all take the high road, Norrholm suggests, when our sensory system signals a higher cortical center in the brain. I’ve seen this before, our brains think, so there’s no reason to panic. Studies show that through repeated exposure, we can overcome our fears and act more reasonably, even in frightening situations.

A problem, of course, is that new things—things we can’t prepare for—happen to us all the time. This past summer, for example, nine-year-old Ezra and I went for a jog on an old railroad bed in Big Pocono State Park, in Pennsylvania. A quarter mile into our journey, we met up with a panic-stricken man and his wife. “We just saw a bear!” the man said, glancing over his shoulder as if the bruin were stalking him.

“It was big!” His wife spread her arms wide.

“How long ago?” I asked.

“Just now.” The man glanced at his watch as if to verify his claim. “It crossed the path and went down a hill. You can keep going if you want to,” he added, “but we’re getting out of here!” With that, the couple power walked on down the trail.

I was torn. The couple’s fear was palpable. Unsurprisingly, culture had saturated me with a fear of bears that bordered on paranoia. At the same time, I’d encountered bears before and knew that while attacks do happen, they’re exceedingly rare. If we kept going down the trail, yes, I was taking a risk. But if I turned tail and fled, I would be sending a message to my son. It would tell him that woods with bears were scary woods. Since bears have repopulated so many rural areas, this could put him on edge the rest of his life. I know many people who are too scared to enter the woods. Nature—the dark and scary forest—so rarely gets a fair shake in fairy tales and children’s books. I didn’t want to perpetuate such misplaced fear in real life.

But I knew that fear, whether innate or learned, is a good adaptive behavior. Without it, the human race likely wouldn’t exist, as fear helped us survive predators and identify threats in the landscape. Had the infamous dodo bird on Mauritius been more timorous, the hospitable species might have been able to avoid the avarice of the Dutch sailors who, legend has it, clubbed the amiable birds with the same cooking pots they tossed them into. Through no fault of its own, the dodo never learned to fear bipedal brutes with wide eyes and empty stomachs.

American culture, in contrast, overplays the unusual. As a result, we’ve been brainwashed to fear many things in nature and all things ursine. A car accident rarely merits a news story. A bear attack, which stirs the imagination of our inner Neanderthal, demands the front page. I have a friend who, right or wrong, once grabbed his four-year-old daughter and ran upon hearing rustling noises in a blackberry patch. Today, his daughter wants nothing to do with trails and hiking. Yes, it could have been a bear. But I’ve also heard many “bears” myself that turned out to be one-and-a-half-ounce eastern towhees foraging in the leaf litter.

“What do you say, Ez?” I asked, looking down at him. “Should we keep going?”

“Let’s do it!” he said without hesitating. As he had with the snakes I’d given him years earlier, he lived on the high road.

“Okay, but be ready to shoot up a tree if I say so!” I instructed. Slowly, we continued down the railroad bed. Sure enough, two hundred yards later, we spied a large black bear sunning on a fallen log quite a distance down the hill. It was a magnificent sight, the bear utterly at peace in its leafy green world. For a while, we watched side by side, saying little. Seeing a bear from the confines of a moving car is one thing. On foot, however, there are whispers of instruction, buzzing insects, and heightened senses of being alive. Like lifting all the cages at a zoo. Sharing the moment made it that much better.

Since leaving the sun-seeking bear in the Pocono Mountains, I’ve hesitated to relay the details of our bear encounter—the decision to advance or retreat—to others. I’ve grown leery of culture-influenced, risk-averse mindsets. I’ve thought it through quite a bit, however. Yes, there were risks. But risks, I’ve realized, are greatly influenced by perception. We may not perceive the risk of riding in a car because we do it so much, but it’s still far riskier than walking in the woods. Everything I do with my son carries risk: taking him to the playground, teaching him to ride a bike, jumping on a trampoline. Even bringing him into the world was a risk. If you focus on all the things that can go wrong in these normal, everyday activities, it’s pretty scary. The flipside, however—incapacitating fear—is far scarier. In the context of healthy, long-term development and self-confidence, what’s the best road to take?

An opportune time to follow up with Emily finally came during ornithology class. We had gone on several field trips and studied lots of different birds. Emily had birded like all the others, and the fear she expressed on the first day had hardly seemed paralyzing. On the way home from a local wetland, Emily was sitting shotgun. “So, Emily,” I asked as nonchalantly as I could, “why are you scared of birds?”

“I’m not really sure,” she answered, looking out her window.

“Did you have a bad experience? Was it too many Hitchcock movies?”

Silence. Emily’s hesitation made me fear (a learned fear, of course) I’d overstepped.

After a long pause, she said, “I can’t remember, but I’m sure it was irrational. All I know is that it started when I was little.” She again fell silent, then turned to me with a wry smile. “By the way, I’m not scared of birds anymore.”

I hoped it was true. Emily’s lack of exposure to the animal world, like my brother’s, was no fault of her own. Unfamiliarity had relegated her to the low road. But Emily was no dodo. Within a few weeks of going out in the field, she’d intentionally gotten to know some of the creatures she shares a planet with. Even better, she learned to call most of them by name. To get there, all she’d needed—all any of us need, really—is a decision to take the high road.