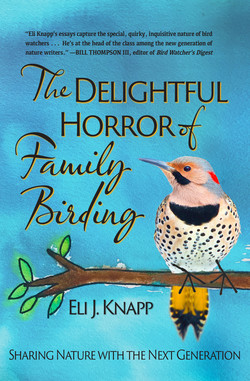

Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSurf scoter

Melanitta perspicillata

6 • CHOMPING AT NATURE’S BIT

Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished.

—Lao Tzu

A surf scoter is a large, black, diving sea duck that I rarely get a chance to see as an inland-dwelling western New Yorker. So when I heard of one resting on a water body about an hour away in Batavia, New York, I brainstormed some errands I could accomplish after a nice quick look at my first scoter. What an easy bird to add to my life list, I thought as I pulled into Batavia’s water treatment facility. Especially compared to the nonbreeding shorebirds I often sought that all seemed to be ever so slight permutations of one another, distinguished literally by shades of gray. But the surf scoter would be a slam dunk. Its boldly patterned head had earned it a colloquial name, the “skunk-headed coot.” The bird should prove easy to find and even easier to ascertain. I’d be home in a jiffy.

I was right on the first count. The bird proved remarkably easy to find. It bobbed like an ebony-colored buoy completely alone in one of the facility’s impoundments. Smiling widely, I lowered my truck window and raised my binoculars. This was fast and easy bird finding at its finest. I focused my binoculars. Magnified ten times, the scoter looked big and black and … headless. The bird, either cold or sleepy or both, had its head tucked so deeply into its coverts I could barely decipher its breast from its rump.

Lots of birds are identifiable without a head. Blue jays, robins, goldfinches—all these birds have irrelevant heads to a busy birder. Not so with scoters. A headless scoter is as useful as a wheel-less wheelbarrow. Akin to trying to distinguish a fish crow from an American crow on a moonless night. My scoter, which my Internet listserv had claimed was a surf scoter, could be a black or a white-winged scoter. I needed to see the head.

I lowered my binoculars and reclined my seat. This was no reason to panic. I’d wait. Sea ducks can’t sleep forever.

But, it slowly dawned on me, they can. Especially headless ones. My alleged surf scoter had no respect for the endless items on my to-do list. It remained as inert as a noble gas. After ten minutes of staring and not getting any errands accomplished, I grew antsy. So antsy, in fact, that I broke a code of conduct I’ve long held. Simply put, I don’t interfere with nature unless absolutely necessary. Yes, I immerse myself in it. I enjoy it in many ways. But unless it’s for teaching purposes, I don’t disrupt it. I like to think of myself as respectfully seated in the balcony when witnessing wildlife dramas, not crinkling candy wrappers in the front row.

But this statuesque scoter had me beaten. I was exasperated. I opened my door and slammed it. Certainly no sleepy scoter could ignore such a gunshot-like sound.

This scoter, however, was an exception to the norm. Its head remained as buried as a Devonian fossil. I opened and slammed the door again. Again. And again. Now I was sounding like a semi-automatic. Still nothing. Either this scoter was stone deaf, had earplugs jammed in its auriculars, or it hailed from downtown Los Angeles.

I looked at my watch. I had to get a vacuum cleaner fixed. If I didn’t buy a garden fence today, our marauding groundhogs might call all their friends for the free buffet. Moreover, I had kids. I was always needed at home. The sand in the hourglass was falling swiftly. For all I knew, this scoter could sleep like this until nightfall. I couldn’t take it anymore. My code of conduct now in shreds, I climbed out of my truck. I slammed my hands on the roof and then, like the scoter, lost my own head. With primeval, hairsplitting yells, I shouted at the scoter and began a series of angry, wild-eyed jumping jacks.

In the midst of my Neanderthal-like madness, I didn’t see the blue sedan until it pulled right up behind me.

Mortified, I tried to transform my witless histrionics into a well-calculated yoga stretch. But nobody in his right mind shouts while doing meditative yoga in a wastewater treatment plant. I had to patch out. I dove into my truck, slammed the door one final time out of spite, and sped away, too embarrassed to glance in my rearview mirror. I drove home skunked by the skunk-headed coot. And try as I have to forget it, my scoter humiliation has resurfaced time and again whenever I’ve found myself chomping at nature’s bit.

I downright drowned in this memory, for example, when I recently uncovered a quote by Ralph Waldo Emerson. “Adopt the pace of nature,” Emerson penned nearly two centuries ago. “Her secret is patience.” It’s a palpable irony that makes me grimace. Why? Because patience, I’ve found in my hectic life as a perpetually behind college professor, routinely proves the most elusive of virtues. But I know Emerson had the magic word. Whenever and wherever I’ve been truly patient in nature, I’ve been rewarded.

Of all the nature partakers out there, perhaps hunters understand it best. Especially the ones who sit out in a blind each autumn. If you ever take the time to ask a hunter what they saw during their dawn-to-dusk vigils they often spend in the woods, you’ll recognize a recurrent theme. Long bouts of stillness interrupted with wondrous spectacles. Chickadees that land on gun barrels. Cooper’s hawks that capture flickers in split-second flights. Porcupines that nibble shoelaces. I even had one hunter (not known for hyperbole) tell me how a red fox sat on his hand for a few seconds and, after realizing its error, vanished like a wraith. Nature moves in punctuated equilibrium. Unlike nature documentaries that compress years of footage into a half-hour, real nature observation has long intermissions between dramatic acts. If you’re lucky enough—and patient enough—to witness a dramatic act in real time, it will sear the memory like a hot iron.

At my stage of life, I have to cultivate patience with intentionality. It’s far easier not to, of course. I found an opportunity when the most observant member of my family, Willow, then ten months old, discovered—and naturally tried to eat—a gorgeous green luna moth that she found in a dusty corner by the sink.

All three of my kids gathered around the recently deceased moth. Other than a slight bird nibble out of one wing, it was intact. Whatever funeral we gave it, this beauty deserved an open casket. The trashcan seemed far too undignified. No, we would scatter the moth to the winds, knowing any number of scavengers would soon delight in this well-preserved, dense package of protein. But first, to fix the spectacle into our own memories, we would paint pictures of it. If any act slows us down and cultivates patience, it is the production of art.

On a little plastic table under a maple tree out front, we ceremoniously spread our supplies around the moth. No masterpiece was going to be produced under these conditions, however. Ezra “accidentally” sprayed us with the hose. Indigo kept bumping the table. And Willow kept trying to eat the paint tubes. But for a few precious moments, we studied the moth and painted our own pictures. And in so doing, we felt the breeze, heard an indigo bunting, and failed to find a shade of green that truly matched the luna’s natural patina.

I’d be lying to say we adopted the pace of nature. But I do believe our corporate compass pointed that way. I’m realistic enough to know that even the cultivation of patience requires patience. Due to our vigil under the maple, maybe my kids will remember the day we found a luna in the house. And what a luna looks like as it blows around an art table.

At the very least, I’m hoping that if any of my kids ever find themselves trying to identify a headless scoter, they’ll be dignified about it. And that they’ll each maintain a well-developed and respectful code of conduct with the natural world. One in which they’ll appreciate seeing a scoter, regardless of what species it is. Nature’s secret, as Emerson wrote, is patience. It rarely rewards those who rush. Paradoxically, adopting the pace of nature is the only way to get ahead. And it’s definitely the only way to get a head you desperately need for proper identification.