Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPeregrine falcon

Falco peregrinus

5 • BIRDERS CAN’T RIDE SHOTGUN

The dominant primordial beast was strong in Buck, and under the fierce conditions of trail life it grew and grew. Yet it was a secret growth. His newborn cunning gave him poise and control.

—Jack London, The Call of the Wild

“So Ezra, when do you think we should—”

“White ibis!” Ezra shouted, pointing out my mother’s window in Florida. I leaned forward on the couch and peered out. Sure enough, Ezra, then five years old, had found two pearly white ibis strolling through a neighbor’s yard. As a fledgling parent, I was both annoyed and thrilled. Should I admonish him for interrupting my question, which I could no longer remember? Or should I congratulate him for both finding and correctly naming one of Florida’s most dazzling species? Before I could decide, his grandmother walked in and joined us at the window.

“I’ve been meaning to ask you what those white birds are.” She sat down slowly to avoid spilling her coffee.

“They’re actually white ibis, Grandmom!” Ezra peppered much of his speech with the word “actually.” And he usually used it with a slightly know-it-all tone. Oh boy. So not only was my son interruptive, he was also pedantic. If any kid was going to get beat up at school, it was the know-it-all pedant with an overt fondness for “actually.” Then again, I was partly proud, as Ezra’s grandmother had a vexing habit of calling every egret, stork, and ibis a “white bird” regardless of their innumerable differences. It drove me—and now Ezra—nuts.

While I would have loved to blame my wife’s DNA for Ezra’s behavior, I knew that mine was the more likely culprit. Through my daily behavior, I had shown Ezra that a man regularly interrupts a conversation to point out a bird, always corrects a wrongly named bird, and often slams on the brakes when a rare bird is spotted (many of these allegedly rare species have a pernicious habit of transforming into common ones upon closer inspection). Normally I do most of the driving. That way, when I see a “rare” bird, I can pull over. But when a rare bird shows up while Linda’s at the wheel, I have modeled for Ezra that an otherwise sane man pounds on the dashboard and pleads to pull over. For safety and sanity, my urgent requests have been habitually ignored. When I can think straight, I credit Linda for her better judgment. And her tolerance. But when a rare bird is potentially afield, it’s impossible to think straight. Muscles tense up. Neurons misfire. And odd and often puerile antics result.

This is why birders can’t ride shotgun.

The problem may lie in a profound misunderstanding between birders and nonbirders. Nonbirders assume that birders go birding. They don’t. Birders are birding. Always. Some of us—the less diehard—occasionally pause to sleep. As soon as we awaken, even before our eyes have opened, we’re birding. Windows don’t open merely for a breeze. Windows open for the dawn chorus. As soon as I’m fifty-one percent cognizant, I’m birding. Even though it may look to nonbirders like I’m cleaning the garage or staining the deck, I’m actually birding. And since I’m always birding, the opportunities to interrupt, correct, and annoy are omnipresent and endless.

I’ve periodically learned to temper my knack for noticing everything avian. I forced it inside during my high school years when I feared my hobby wouldn’t be deemed cool enough for my soccer-playing comrades. Several girlfriends were likewise none the wiser to my dual love interests. And the stress of grad school squashed it for a while. But with my diploma in hand and a job that includes teaching ornithology each year, the out-workings of my birdy brain have oozed back to the surface like an oil seep.

My decorum was tested again during a recent trip to the Everglades in Florida with my obliging parents. Wanting to get a sense for the sinuous rivers of grass, we departed for a two-hour boat tour from Flamingo Point. Since it was off-season and an odd midday hour, I shared the boat with about seven other folks, all of whom seemed normal enough. Although antsy to see great birds, I was resolved to appear as balanced and well-mannered as those around me. The tour started wonderfully. I kept my binoculars mostly lowered, made small talk with others, and laughed when the tour guide made unmemorable jokes about mangroves.

But then my façade fell away. Out of the corner of my eye, about thirty yards away, I saw an abnormal-looking mourning dove. Wait, that was no mourning dove; it was a white-crested pigeon! Knowing these birds were restricted to Florida’s southern tip, I desperately wanted a better look at the bird that had now alighted atop a mangrove. I needed to be sure of my ID. More importantly, I needed to slow this darn boat down. My dilemma resurfaced. Should I try to stop the boat? Was it appropriate to hijack a general tour for a bird? Not just a bird, a pigeon. A pigeon! These pleasant-looking people would surely get mad. At least one would want me tossed to the gators.

Despite my resolve, my zeal exploded like fireworks. “White-crested pigeon!” I yelled, pointing off the starboard side. But the roaring engine reigned supreme. The skipper neither saw nor heard me. Or, more likely, he pretended not to. I’ll never know. His large, dark sunglasses revealed nothing more than the requisite stoicism that comes with leading the same tour untold times a day for untold years. The other passengers heard me though. As did my parents. I sensed their normal parental pride dissipate as quickly as the pigeon did in my binoculars. Kindly, most of the others feigned interest with a curious nod or a sympathetic smile.

We finally slowed down next to a dense stand of trees that all looked like they were walking in the water. The skipper slowly unhooked the boat’s microphone and in a remarkable monotone, taught us how to differentiate black and red mangroves. I felt cheated. He had passed over one of America’s most geographically restricted birds—the white-crested pigeon—to robotically instruct us about adventitious roots?! Granted, mangroves were cool. But they registered far below birds on my biophilia meter. Next time, I vowed, this barge would brake for birds. I’d make sure of it.

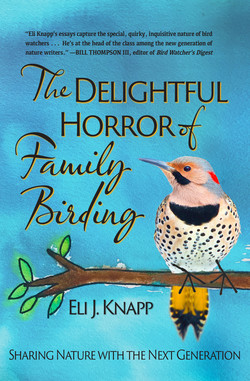

Next time came just twenty minutes later. While speeding into a large lagoon, I saw a bird that was indisputably cool. He or she was perched high on a snag and looked downright debonair. A peregrine falcon. While not extremely rare, peregrines are always a treat to see. Especially this one, that appeared utterly apathetic to the noise of our boat’s bombastic approach.

I glanced at the skipper. Like before, his face belied no emotion. Despite looking straight at the bird, he didn’t seem to notice it. We weren’t slowing down. What?! If anything we were speeding up. Still sore about the pigeon, I was not going to lose this peregrine. If we could halt our pleasure cruise for mangroves, alligators, and air plants, we had to stop for the fastest animal in the world, a bird that when clocked by Ken Franklin in 2005, hit 242 miles per hour.

Two hundred forty-two miles per hour! When Usain Bolt hit his top speed of 27.8 miles per hour in Berlin, we gasped in awe and awarded an Olympic medal. The world reacted similarly to Secretariat’s 49 miles per hour at the Belmont Stakes. Yes, speed is relative. But peregrine speed is relative and superlative. Everything about them is modified for it. Small, bony tubercles line the nostrils like inlet cones on jet engines. As air rushes in the nostrils it is slowed by rods and fins. These reduce the dramatic changes in air pressure and prevent lung damage, allowing the bird to breathe. An additional secretory gland prevents the corneas from drying out while a third eyelid—a nictitating membrane—spreads its tears and clears debris without sacrificing keen vision. The menacing dark markings around the eyes reduce glare. Keen vision and glare reduction is essential. Because peregrines don’t just defy death, they inflict it during their miraculous stoops.

While the peregrine is falling like a meteorite, it’s applying mathematical principles that would have impressed Pythagoras. Speed in a stoop is largely determined by drag coefficient. The lower the drag coefficient, the faster a falcon can free fall. Peregrines fold back their wings and tail, tuck in their feet, and drop. With a drag coefficient of 0.18, the crow-sized peregrine calculates exactly when to blast through the wing of an oblivious mallard, speeding along on its own trajectory at a cool sixty miles per hour. The peregrine slightly adjusts its tail and tucked-in primary feathers to alter its trajectory as it tracks its prey. The impact angle is critical; a direct hit can be suicidal. To live through an assault, a peregrine needs a glancing blow, which it makes with a clenched foot. A stunned, spiraling mallard is enough.

But the physiological feat isn’t over yet. The falcon still has to slow its speed without ripping its wings off in the process. It accomplishes this with a U-shaped dive, gradually arcing upward, allowing gravity to slow it down. On the upswing, it uses its talons, now unclenched, to snatch the witless duck from the sky. If I were a mallard, I’d choose death by duck hawk. Alive one second, dead the next. Fast and furious.

But no. The skipper didn’t see the falcon. My parents didn’t see it. Nobody saw it. We had to see this!

I leapt up, gesticulated wildly, and shouted, “Peregrine falcon!” at the very top of my lungs. Weary heads snapped up all around me, obviously wondering why a binocular-toting lunatic had been allowed on board. No longer able to pretend he didn’t see me, the skipper cupped his ear, indicating he couldn’t hear me. I shouted again, stumbling into a railing as I did so. Ever so reluctantly, the skipper eased off the accelerator and grabbed the microphone.

“Folks,” he said, somehow managing to sound both bored and annoyed, “we’ve got what our friend here calls an American falcon.”

“A peregrine falcon!” I interrupted. “Peregrine!” I repeated more loudly. The captain ignored me.

“Yes, yes,” he said again. “An American falcon. Oh look, there it goes,” he added without a hint of disappointment, replacing the microphone in its holster on the dash. With a few strong, regal wingbeats, the peregrine lifted off and was soon a speck on the horizon. I couldn’t blame it. I would leave, too, if I had been called an American falcon despite having a geographic range that spans the globe.

The skipper pushed back the throttle and I lurched back to my seat. Too embarrassed to make eye contact with even my parents, I stared off into south Florida’s shimmering water that looked decidedly less tranquil than it had when the trip started. I was defeated. If I was the skipper of this boat, I concluded grumpily, I’d brake for birds and call them by their proper names. Whether in a car or on a boat, riding shotgun was painful indeed.

In the midst of my self-righteous stupor, I noticed a line of beautiful white birds soaring some fifty yards off the bow. I lifted off my seat but hastily forced myself back down. No. Not this time.

I wasn’t going to shout it out to my fellow passengers. I’d annoyed enough people for one day. Yes, I was always birding. That didn’t mean I had to force others to do so, too. After all, even I had been annoyed by my son’s interruptive and pedantic insistence on accurate avian nomenclature. If the other passengers saw the beautiful white birds and enjoyed them—great. If they didn’t, they didn’t. But I surely wished that everybody on this blasted boat knew one final thing. Something Ezra would have wished as well. Yes, these were white birds. But actually—and far more satisfyingly—they were white ibis.