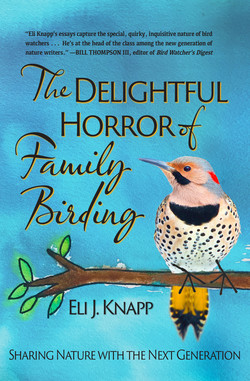

Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAndean cock-of-the-rock

Rupicola peruvianus

7 • THE BIRDS AND THE BEES

Dressing up is a bore. At a certain age, you decorate yourself to attract the opposite sex, and at a certain age, I did that. But I’m past that age.

—Katharine Hepburn

Every kid learns about sex in their own way. I am a case in point. As is true for many kids growing up in the country, a cow pasture formed the border of my backyard. When my friends and I weren’t daring each other to pee on the electric fence, we tended to ignore the bucolic behemoths that placidly ignored us in kind.

But one spring morning, I could not ignore my lazy, lifelong neighbors. Glancing out the window, I noticed a large bull that seemed to be pushing a smaller, wide-eyed cow across the field like a wheelbarrow. The bull completed several lascivious laps around the pasture with his concubine before falling off with an exasperated bellow.

Like lots of coming-of-age kids, I was both curious and confused. The tryst did not seem consensual. But each time the female outran her amorous assailant, she’d stop and wait for him to remount. Not knowing what would happen next, I remained where I was, transfixed by this unexpected cattle concupiscence. I never heard my father behind me until he spoke.

“They’re having sex,” he remarked dryly. As the bull remounted and the wheelbarrow routine resumed, my dad couldn’t resist adding a few more titillating aphorisms, bespeaking his rural Tennessee roots. Mercifully, he left for work before I could respond and reveal any further embarrassment. This episode, which felt more like a low-budget beer commercial, was my first lesson about sex. And I obviously never forgot it.

Now with young children of my own, I jealously applaud my father’s straightforward, opportunistic approach to sex education. I share his style, I’ve learned, but lack his gumption. And since I also lack a pasture out back, I’ve harbored a cattle-less conundrum about the best way to proceed with my own off-spring.

Figuring that water is purest at its source, I turned first to the sex doctor himself, Sigmund Freud. But of all Freud’s writings on sex, it was an unrelated quote that struck me the deepest: “When inspiration fails to come to me,” Freud wrote, “I go halfway to meet it.”

My halfway ended up being pretty far: the foothills of the Andes Mountains in Ecuador. But as Freud predicted, inspiration did indeed meet me, arriving five minutes after I settled down with a dozen of my bleary-eyed college students at a well-known lek, a place where male birds regularly display for females in hopes of landing a mate. We were after one particular bird—the cock-of-the-rock—that has drawn birders from time immemorial. One Andean cock-of-the-rock would have sufficed. We found a half-dozen. The fantastical, blaze-orange birds bobbed their heads and riotously sang as if their lives depended on it. Because that’s just it, we slowly realized: their lives did depend on it.

Everything about the cock-of-the-rock, as with the cattle I’d observed decades before, was predicated on procreation. Pseudo-scholar or not, Freud rightly theorized that sex drives life. Charles Darwin coined the term sexual selection, a force dictating survival as powerfully as his more famous concept, natural selection. At its simplest, sexual selection is nothing more than discerning females choosing the most beautiful—or the fittest—males. Victorian culture wasn’t ready for Darwin’s ideas. Sexual selection gave too much power to women, so Darwin—and his 898-page monograph on the subject—was politely ignored.

But culture changed and as it did, a slew of other scientists put Darwin’s cockamamie theory to the test. They hacked tails off some birds, glued extensions on others, and painted various plumages. Then they did things meddling scientists typically do, assiduously numbering nests, measuring mating attempts, and enumerating eggs. Details differed but the synopsis was the same. In short, female birds love fashion, novelty, and extravagance. In the animal kingdom, crazy long tails, a cacophony of colors, and a jumbled assortment of other doodads are downright arresting to the lady folk; the more otherworldly the outfit and the more dazzling the display, the more smitten the ladies become.

“The sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail,” Darwin once lamented, “makes me sick.” But later, in the light of lovemaking, the tail’s purpose became clear. True, a male peacock’s train, toting over 150 elaborate eyespots, makes little sense to the story of survival. But in the story of sex, eyespots are billboards for health and vigor. You can’t be loaded down with parasites, for example, if you’re flitting about the forest in an ostentatious overcoat.

Unsurprisingly, the cock-of-the-rock first caught my attention due to its name alone (juvenile humor may fade but it never disappears entirely). I quickly learned that cocks-of-the-rocks, if that is indeed how you pluralize this bird, are not the worst offenders. Seemingly every bird we encountered in the tropics, and even some in my native state of New York, was in some sense surreal with superlative names to match. Watching the males of species like the beryl-spangled tanager, long-tailed sylph, and flame-faced tanager almost required sunglasses. To females, these shimmering studs are dreamy. Now educated in Freud and Darwin, I can only imagine how a female booby’s heart must flutter when she looks licentiously upon her consort’s powdery blue feet.

There in the morning mist, I realized my students were grasping the power of sex on species survival as memorably as I did so many years back with my convenient cow pasture. So I channeled my father’s opportunism. “What about humans?” I asked my students once we’d left the lek. “Surely sexual selection doesn’t act upon us?”

A pause.

Then, sure as a black-tailed trainbearer’s tail, the comments came. Tanning, high heels, bodybuilding, nose jobs, extreme dieting, hair dyes, make-up, enhancements, reductions, Botox … We’re so steeped in sexual selection we’ve almost ceased to see it. For our species, it’s less clear who’s dressing up for whom, and who’s doing the choosing. Nuances aside, the many multi-billion dollar industries that result from Darwin’s simple theory are testament to its unparalleled presence and power.

Despite clichés that warn me against it, I continue to—at least initially—judge books by their covers. But watching tanagers and trainbearers has exposed me to double standards I didn’t know I had. Although I like to think otherwise, I’m just as susceptible to preening and prancing. So I’ve resolved to change. Not cataclysmically, of course. Enough to make me opt for spending thirty minutes on a walk instead of the weight room, veering away from these many-mirrored rooms devoted to vanity. More importantly, I’ve learned that lots of human nature is as brainless as the backyard cows I once watched.

No, I don’t have the luxury of a pasture out back to educate my son about sex. But I’ve got a creek, a forest, a whole ecosystem. For learning about the birds and the bees, we’ll have to forgo cows. And I think we’ll leave the bees alone, too. I’m not worried. As I learned in Ecuador, the birds will more than suffice.