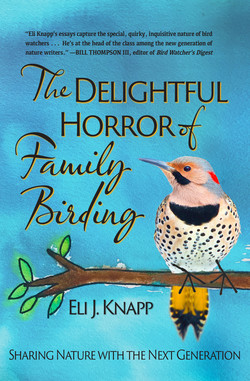

Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

One touch of nature makes the whole world kin.

—William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida

The flat tire wasn’t unexpected. We’d suffered six already caravanning across the cheese-grater roads of East Africa. What I didn’t expect, however, was a beautiful black and white bird with an outsized bill just off the road from where our equally outsized truck had suddenly lurched to a stop. Toucan Sam leapt to mind. I had made a habit of identifying—and often failing to identify—the incredible wildlife with which Tanzania overflowed. Nearly every day of this semester abroad, I had thumbed through my ratty field guide while madly spinning the focus knob on my semi-functioning binoculars. This bird was new. It was some kind of hornbill. But what species? With at least twenty minutes to kill, I decided to find out. To do so, I needed a closer look.

I made my way past the twenty other students, somnolent in their seats, and climbed down out of the truck. Unsettled by the sudden bipedal commotion on this little-traveled dirt road, the ungainly bird flew deeper into the acacia scrub. Determined, I went in after it. I wove around several head-high thorn bushes and glimpsed the bird again. Just as I raised my binoculars, it flew off to another perch deeper in. We played this aggravating game of hide-and-seek for several minutes until it occurred to me that I should get back to the truck lest I hold up the gang.

I gave up on the bird and turned to head out the way I’d come. Just as before, I wove around thorn bushes. I expected to encounter the road … but no road appeared. I stopped and listened, hoping to catch sounds of my group. Nothing but the mechanical throb of cicadas. Despite the heat, a shiver ran down my spine, causing me to—against my better judgment—pick up my pace. For several more minutes, I speed-walked through identical-looking trees, unwilling to admit a horrifying fact: I was lost. Not only was I lost, but I had no food, no water, and I seriously doubted whether anybody had seen me leave. Even worse, chances were that with the tire changed, they would unwittingly leave without me.

I willed myself to stop and regain composure. A breeze of hot, dry wind sent small desiccated leaves swirling around my expensive shoes. A black beetle scurried into a penny-sized hole in the hard-baked African soil. If only I could do the same. Here I was, a confident twenty-year-old, a recent member of the National Honor Society, yet more helpless than a newborn wildebeest.

Minutes dragged by, and the sun’s rays increased their slant across the orange-red earth. I picked a direction, yelled a few times, and hoped for a response. None came. I glanced down at my watch. Surely the tire was changed by now. Ahead in the loose dirt—footprints! Hopeful, I bent down and examined them. My own. I was walking in circles.

In the midst of this new wave of panic, I heard the soft but unmistakable sound of bells. Bells! Was Santa’s calendar skewed in Tanzania?! Savoring a rush of childlike giddiness, I beelined toward them. But they weren’t reindeer I found in the African bush; they were goats, dozens and dozens of them. Before I knew it, the amoeba-like herd engulfed me, munching on the move. I stood my ground as the unfazed animals marched around me, likely annoyed that I wasn’t palatable. Where there were goats, I reasoned, there were people. And if there were people, I would be spared.

“People” turned out to be a knobby-kneed boy whose head maybe reached my belly button. A burgundy cloth hung from one shoulder and tied around his waist with a frayed piece of sisal. He couldn’t have been older than twelve. Despite being startled to find a white guy out in the bush, he didn’t run. He just stood and looked at me, letting his goats disappear into the scrub.

Since my Swahili wasn’t good enough to explain my predicament, I dropped to one knee and sketched a line in the dirt with a small stick. Then I tried to imitate a truck’s diesel engine. Wordlessly, the boy watched my poor charade, nodding slightly. Then, he spun on his heels and started walking. His herd—all his responsibility—was abandoned.

I followed like an imprinted duckling. There was no way this boy was going to get away, even if it meant ending up in a distant village. Fifteen minutes later, we popped out on a road—my road. Fifty yards away was the truck. Our driver was tightening lug nuts with a large tire iron, and the other students, oblivious to my panic-stricken absence, were playing hacky sack in the road. I hadn’t been missed at all.

Overcome with relief, I pantomimed for the boy to stay, that I wanted to give him something. I ran to the truck, rummaged through my duffel bag, and found some Matchbox cars I had brought to Africa as token gifts. Perfect. I grabbed them, jumped off the truck, and ran back. The boy was gone.

Immanuel Kant once wrote, “Man is the only being who needs education.” What Kant didn’t clarify was what form of education man needs. As I discovered in the Tanzanian bush, my fifteen years of western-based education held little practicality. For life skills, I had nothing on the young goatherd.

Knowledge comes in many ways and from many sources. Most of mine up to that point had come in the controlled environment of a classroom. My teachers held forth in typical classrooms, in which teachers teach and students learn. In Tanzania, my education was upended. It became experiential, and much of it came from nature itself. It also came from unexpected sources, including small goatherds.

These lessons were hardly profound. But they matter greatly. Now, as a parent and a college professor, it seems I relearn them weekly. The essays in this book chronicle this journey. At times, it’s been difficult and disorienting. But it’s been delightful, too.

Life has afforded me new eyes to see nature. In that roller-coaster year before we wed, Linda called me excitedly from work in Santa Barbara.

“Is everything okay?” I asked, unused to her calling midday.

“There’s a beautiful yellow-orange bird outside my window! It has a black bib,” she added.

“Is it a goldfinch or a house finch?” I asked, naming the first birds to come to mind.

“The bill is too slender,” she replied confidently. Not yet keen to the West Coast birds, I couldn’t come up with any alternatives.

“Can you draw it?” I asked. She came from a family of artists—I was confident she could.

“I’ll try.”

Later that night, Linda produced a sketch she’d done on a piece of scrap paper. Just a few simple but well-placed lines. Quick, yes. But obvious field marks and expert proportions. No doubt a hooded oriole. I was smitten, both with the bird and the artist. This was—and is—who she is. Linda overflows with curiosity about the natural world. While I’m obsessed with the creatures around us, Linda’s more balanced, thank heavens. While she’ll crane her neck out a window to see a cool bird, I’ll careen down a ravine. Our mutual interest is expressed differently but unites us nonetheless. I held onto the sketch for years. Fortunately, I’ve held onto Linda even longer. Her influence on my journey and that of our children lies behind the stories that follow.

I used to think I’d wait to write a nature book until my kids had grown up and left. But then I entered the forest with Linda, my kids, and later my college students. Everything changed. With Ezra, Indigo, and Willow at my side, I saw nature through young, impressionable lenses. Wonder deepened—the same wonder I’d felt watching the hornbill in the featureless thorn scrub. The richest book I could create, I realized, would be one that captures this wonder in the mixed-up, rarely planned moments that make up life.

I am an odd duck: a hybrid anthropologist-ecologist by trade who happens to have a special love of birds and nature. While I haven’t forced these interests on my kids, I have immersed them in it. A feeder is visible from every window of our house, and bird paraphernalia—carvings, feathers, and field guides—line every shelf. I even named one daughter Indigo after one of my favorite birds, the indigo bunting (I may or may not have known that another group of birds, the indigobirds, are renowned for their ability to parasitize other birds). A second daughter, Willow, is bird-friendly nomenclature as well. More than occasionally, however, I overdo it.

“No more birds, Dad!” Ezra occasionally shouts from the back seat after I’ve pulled over to get a better look at an overflying raptor. But in between his back seat directives, I’ve caught him craning his neck, too.

A few years ago, while enjoying a family dinner around the table, Ezra, then six years old, couldn’t conceal his mushrooming bird knowledge. “We’re going to go around in a circle and everybody is going to tell us what their day’s highlight was,” I had instructed, attempting to rein in the raucous dinner cacophony, focus the kids’ attention on mealtime, and teach them to take turns speaking.

“I’ll go first,” Ezra said, waving a macaroni noodle around on his fork like a baton. “I saw an indigo bunting while on the bus today! It was by the big bend in the road,” he added, as if more detail would verify his claim. His blue eyes held mine, waiting for my reaction. While he loved to get a rise out of me, this time at least, he wasn’t ruffling my feathers.

I have no idea if any of my kids—or my students—will one day enjoy nature as much as I do. But at the very least, they’ll be familiar with it. Since enjoyment is contingent upon understanding, familiarity seems like a step in the right direction.

This collection of essays spans a five-year period of my life as a fledgling father. They’re arranged thematically, not sequentially. As a result, the ages of my children fluctuate forward and backward, which may be disconcerting to the careful reader. Rest assured, I haven’t sired any Benjamin Buttons. While ages change, the mutual learning we all undergo doesn’t. Nor does our discovery of knowledge in unexpected places, or our collective familial decision to let nature lead.

One of the unexpected places popping up often in these pages is Africa. The continent has shaped my family mightily over the years, luring us back in spite of our best attempts to put down deeper roots in the States. Africa first called us as students and now as professors. Linda and I teach, yes. But we still learn far more, annually treated to profound lessons from wise and generous people who live far closer to the land than we do.

All the stories emerge from my experiences as a husband, father, professor, and lifelong lover of birds and nature. Some of these experiences have been delightful, some horrible, and most a combination thereof. This book, like life, isn’t about a destination. Rather, it’s about process, false starts, and learning from mistakes. It’s a book that shows that the youngest among us may appreciate nature best, and that life is at its richest when we go outdoors together and keep our eyes open. Lastly, it’s a book about coddiwompling. Like the ivory-billed woodpecker, this word doesn’t seem to exist regardless of how badly I want it to. Its definition: traveling in a purposeful manner toward a vague destination. This book examines the intersection of our lives with birds. Hopefully it begets a relationship. Where that relationship ends up is anybody’s guess. Perhaps to greater knowledge, deeper introspection, or a more satisfying view of nature. A little ambiguity is good; I’m convinced that the best paths take us to places we didn’t know we wanted to go.

Dr. Elliott Coues, a wild-eyed birder from a former century who did his share of coddiwompling, once wrote: “For myself, the time is past, happily or not, when every bird was an agreeable surprise, for dewdrops do not last all day; but I have never walked in the woods without learning something that I did not know before … how can you, with so much before you, keep out of the woods another minute?”

Like Coues, I can’t keep out of the woods another minute. So I may as well take my kids, my students, everyone. Nature has so much to teach us. To learn, we may have to give up control and let nature lead. Maybe, like the birds, we all just need to wing it.