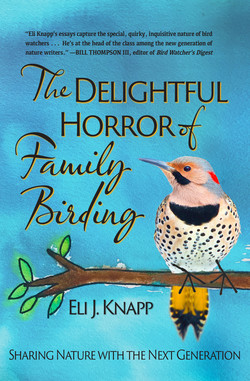

Читать книгу The Delightful Horror of Family Birding - Eli J. Knapp - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGreat gray owl

Strix nebulosa

8 • SEARCHING FOR A LANDSCAPE IDENTITY

Tell me the landscape in which you live and I will tell you who you are.

—José Ortega y Gasset

“Great gray owl!” my son, Ezra, shouted from the backseat. I hit the brakes and pulled over, Ezra and I craning our necks out the side windows.

“Nope.” I lowered my binoculars. “Barred owl.”

“Gimme your bins, Dad!” Ezra demanded, his absence of manners almost as troubling as his incredulity. I glanced at him in the rearview mirror. Here was a scientist—a born skeptic—squeezed into a nine-year-old body. “Guess you’re right,” he conceded, handing back my binoculars.

We were slightly deflated. Granted, any owl was cool. But we were after a great gray, undisputed Zeus of the owl pantheon. Although exceedingly rare, we had expected a great gray here in this nondescript meadow in the mountains of southern Oregon. Why? For a simple reason: I had seen one here before.

Other birders have confessed they share in my suffering. It’s a common, yet chronic, disease. The symptoms are straightforward but the cure, if there is one, isn’t. It goes like this: If you see something cool, the next time out—perhaps even years later—you expect to see it where you did that first time. My particular manifestation of this odd, nature-lover affliction is even worse. I often expect to see what I’ve seen before not only in the same tree, but perched on the very same limb.

Species themselves are partly to blame. Some exhibit, in the lingo of behaviorists, strong site fidelity, otherwise known as philopatry. Derived from the Greek, meaning “home-loving,” philopatric critters are loyal to localities. Some megapodes, or ground-laying birds, in Australia, for example, will reuse the same mound for a nest every year, only abandoning it when calamity strikes or it literally falls down around them. That’s breeding-site philopatry. Another form, natal philopatry, is living out your years where you were raised. This coming-back-to-our-roots is the form most of us can relate to. It also explains my particular fondness for a pair of phoebes that faithfully chooses the same eave under my porch year after year after year. When this pair passes on, I’m confident their kids or grandkids will take over. They’re attached and so am I.

But nature is varied. Many other species refuse to don such straitjackets. When they’re not manacled to a nest or frantically feeding fledglings, they’re prone to wander widely. Others are more nomadic, dyed-in-the-wool vagabonds—the human equivalent of our wanderlust friends that head west in their vintage Volkswagen camper vans. I understand all this. Even so, each day I drive home from work, I scan the same snag or ditch or fencepost, hoping for the same owl or hawk or meadowlark that I saw once before. Rain or snow, if my friends aren’t where they’re supposed to be, I’m let down. But hope springs eternal, and tomorrow I’ll scan the exact same places again.

Part of the problem is that the roots of this see-it-once-expect-to-see-it-again condition are buried in a spot that’s only accessible to a brain surgeon: the medial temporal lobe of the hippocampus. This vast neuronal network is the wardrobe in which our mental maps and memories are hung. When we revisit a place where we experienced something memorable—say, saw a great gray owl—the place cells in the hippocampus fire anew. As Jennifer Ackerman writes in The Genius of Birds, our memory of a thought is married to the place where it first happened.

This is why, I’m guessing, many birders I know are as philopatric as some of the species they search for. We birders pay attention. Consciously or not, we’re perpetually scanning: tree limbs, rooflines, hilltops. We study contours, scrutinize specks, and look for irregularity. Usually we find nothing. Occasionally, lightning strikes. And when it does, and that irregularity turns into a great gray owl, it’s satisfying in the same way that finding your lost car keys is, provided they’re in a spot you’ve already looked twelve times, of course. Over time, our well of memorable sightings deepens and our connection to place—our place—grows stronger. Certainly the lure of watching bountiful birds in exotic locales is ever enticing. But my circle of birder friends agree with Dorothy: there’s no place like home.

These feelings form, in the words of psychologist Ferdinando Fornara and his Italian research team, a landscape identity. For Fornara, this identity includes “a set of memories, conceptions, interpretations, and feelings related to a specific physical setting.” It goes like this: The more time we spend in an area, the stronger the bond. Everybody who lives in a place for a while develops some sort of landscape identity. Seems pretty obvious. Less obvious, perhaps, is my guess that birders—and surely botanists, lepidopterists, and all stripes of nature lovers—form stronger landscape identities than others. Why? Because it’s not only the birds we grow fond of. The habitats that house the birds—the swamps, brush piles, and power lines—become just as wonderful. Because of this, birders and other nature-lovers can find beauty in places others can’t.

This is why I wasn’t too surprised when I saw a house advertised recently on an online birding listserv. It was near, but not on, Lake Ontario. Rather than lakefront with expansive views, this house was across the street, its view obstructed by other houses, fences, and hedges. “Great house and migratory stopover site,” the ad read. “Rarities not uncommon.” Despite the oxymoronic last line, the house undoubtedly lived up to its billing. Every spring and fall, songbirds, intimidated or exhausted by the Great Lake, probably dropped by in droves. The birds didn’t need waterfront and limitless views. They wanted brushy tangles, hedges, and swampy areas—places with food. The advertised house was one refined aesthetes with deep wallets would scoff at. Quite literally, it was a house for the birds. And since it was, the savvy house lister went after birders.

System administrators promptly removed the listing, which didn’t surprise me either. It was a site for listing birds, not houses. Regrettably, I wasn’t able to read the fine print before the ad was pulled. Perhaps it was an opportunistic birder who needed to sell the house quickly. I can’t help but hope on a deeper level that the house seller and I are the same species, one with a stronger-than-usual landscape identity, made even stronger by the great birds that we can’t keep ourselves from searching for.

Just around the bend from where I spent my childhood summers in Pennsylvania lies a bucolic township of rolling fields called Brooklyn. This Brooklyn, with less than 1,000 people, couldn’t be more different from its outsized bigger brother. It’s iconic farm country with little notoriety except for one thing: Actor Richard Gere grew up there. Once or twice a summer, my dad took me out to breakfast, intentionally swinging by Brooklyn on the way home. And every time he did, his line was the same. “Richard Gere grew up here, you know.” I nodded and smiled, looking out my side window as if expecting to catch the Golden Globe Award winner out on a tractor. Gere only occasionally visits Brooklyn nowadays. But even so, he lends the otherwise anonymous map dot a certain cachet.

The presence of ruffed grouse does the same. Renowned ecologist Aldo Leopold once wrote:

Everybody knows that the autumn landscape in the north-woods is the land, plus a red maple, plus a ruffed grouse. In terms of conventional physics, the grouse represents only a millionth of either the mass or the energy of an acre. Yet subtract the grouse and the whole thing is dead.

Leopold was writing about more than mere ecological equations. He was expounding on the importance of that slippery concept called value—subjective value of landscape—and the importance of cryptic little chicken-like birds. Granted, tourists will never flock to the north woods to gape at coveys of grouse teetering about the underbrush. Leopold knew that. He also knew that grouse aren’t even vital for ensuring ecological function (helpful, yes, but not essential). He was after intrinsic value. That grouse are there, even if rarely glimpsed, is what counts.

I learned this lesson early and in an unexpected way. The movie Jaws played on our old, boxy TV in the family room. My nerve-wracked, eight-year-old frame was wedged between my two older siblings. Like millions of other viewers, I was terrified. Not whenever the great white appeared, but, rather, when it didn’t. When it lurked below, John Williams’s infamous score launched me into apoplexy. Two-thirds of the film, the shark is submerged, shrouded in mystery.

It was a happy accident. Spielberg disliked the sharks he’d commissioned. They weren’t frightening enough. With time running out, he opted to keep his great white concealed. It was pragmatic, Hitchcockian, and genius. Jaws quickly became the highest grossing movie in US history, winning three Academy Awards and spawning musicals, theme park rides, and best-selling computer games. More importantly, it showed us all that the mere idea of a shark is more mesmerizing than the shark itself.

I’m convinced that birders, and most other nature enthusiasts for that matter, understand this idea. What we have trouble understanding, however, are attempts that scholars sometimes make to quantify such value. In 2016, Fornara and his cadre of researchers, the same folks who coined “landscape identity,” attempted to quantify the subjective value people feel about place. It was a simple experiment: photographs of natal and foreign landscapes were placed in front of subjects who were asked to evaluate their feelings of “self” in response. Unsurprisingly, photos of one’s native region tended to produce stronger emotions. Yes, the researchers dryly concluded, research lent some quantitative support to the theory of landscape identity.

Something about the act of objectifying subjective feelings doesn’t sit right. In my graduate seminars, I well remember my distinguished professors cogently arguing about the need for attaching dollar signs to ecosystems and the services they freely render. As a professor myself, I’ve assigned heavy-duty readings on the subject, like “Economic Reasons for Conserving Wild Nature,” which appeared in Science not too long ago. The logic is straightforward. Humanity benefits from nature. Such benefits should incentivize us to conserve it. But they don’t. The benefits we enjoy from ecosystems are difficult to commoditize, making them even more difficult to capture with conventional, market-based analysis. So humanity continues to “convert habitat”—a euphemism for destroying it—relentlessly.