Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVII. A FREEDOM CRUISE

SUDDENLY I WAS NO LONGER sleeping in my own bed in Hannover. Grownups talked about being refugees from the Holocaust. Here in free Amsterdam we saw no Gestapo, no burned synagogues, no Star of David armbands and no food shortages. But I missed our own apartment.

We were visiting Mutti’s youngest sister Käthe, her husband Isaak Wurms and their new baby, my only cousin, Aaltje. I can’t explain how we got there. Events happened quickly and no one trusted me with information. I do remember some packing. However, having never taken a trip anywhere, packing had no significance for me. Mutti, in her super orderly manner, was always moving things from one box to another to assure absolute cleanliness, household purity. However, these new boxes—Mutti called them suitcases—were different. They had handles.

In Amsterdam I played with my new cousin as much as one can play with an eight-week old baby. Aaltje slept in her cradle most of the time. When awake, she cooed or cried. Her smell often reminded me of toilets when someone is sick. When she cried or stank, I left the room to play with Onkel Isaak.

Sometimes Mutti made me sit in a rocking chair. Then she’d place Aaltje on my lap with her little head in the crook of my arm. “You should be good to your little cousin,” Mutti instructed. “Sing her some of the songs you make up. One day you’ll be like a big brother to her.”

I had no idea what “big brother” meant nor had I ever met one. I am an only child and all my relatives were childless or had only one child.

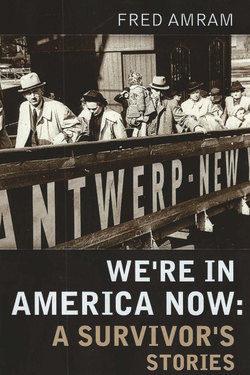

Pennland steamship

Mutti liked to create titles for me. She often told me to act like a “man” and that I was her kleiner Mann, her “little man.” I hated that even more than “big brother.” I didn’t want to be a man. I wanted to be cuddled like Cousin Aaltje. Life had been pretty scary for the past three years and now we were in a strange land with a language that I didn’t understand. Didn’t Mutti understand that Papa was no longer in slave labor and he was again the man of the house? I wasn’t ready for the responsibility of being a big brother or a man—even if it was only a little man.

Early one morning I was told to dress in my Lederhosen and a white shirt. While eating my oatmeal, I watched Mutti and Tante Käthe cry a lot. Mutti, who considered herself perfect in every way, dropped a teacup. Shards slid all around the kitchen. Hysterical sobs.

After a round of hugs, Mutti, Papa and I left the Wurms household with our three little brown suitcases. The shiny golden locks glistened in the sun. Mutti carried keys that fit into holes in each lock. She kept the tiny keys in a little compartment in her pocket book. My suitcase was smaller than the other two but I still struggled to keep it from dragging on the ground.

I remember a train and lots of walking. In a few days we were at a dock in Belgium. Here people spoke a language that was totally different from German. It seemed that after every train ride one had to learn a new language.

In Antwerp, Mutti, Papa and I crowded into a small cabin on the Pennland. Papa announced with a grin, “We’re on our way to the land of milk and honey.”

“Hooray,” I shouted as Papa lifted me high and danced around the tiny room.

“I’m about to be sick,” moaned Mutti.

First, two weeks in Holland, then several days in Belgium and now two weeks on a 600-foot ocean liner. It all seemed like a great adventure to me. This exodus reminded me of the story we tell at the Passover Seder about the flight out of Egypt, crossing the Red Sea and then spending forty years in the desert. Except I saw no desert. We were surrounded by water. Did the captain know how to get to the milk and honey without any landmarks? No streets, no buildings, no parks. Was God guiding the captain like He guided Moses?

The Pennland was not a luxury cruise ship. Everything seemed cramped. But I was happy to be free of the Nazis—although I didn’t feel totally comfortable on a rocking boat with water on all sides.

Our cabin had only beds. There may have been a dresser but I remember only beds. Papa lifted me onto the top bunk of a double-decker where I slept quite comfortably. Papa slept on the bottom bed and Mutti had her own little bed. We shared a tiny bathroom down the hall from our cabin with other adults. I didn’t see any children.

Our little room had one little round window about the size of my face. Huge waves splashed against the window most of the time. Once we left port, I never saw anything but angry water. The slapping of the water against the ship didn’t keep me awake but Mutti complained that the noise gave her a headache.

Rough seas during most of the two-week voyage meant that passengers rarely visited the dining room. Nor did they visit the deck, which was often covered with water as the boat tipped from side to side and the fierce wind and rain followed us across the ocean.

I became the crew’s mascot, a healthy little boy who was always hungry. When all the other passengers were sick, I ate in the galley with the sailors. The food was much more plentiful than the rationed fare at home in Germany. I tried to eat as much as the crew members did, although they kept warning me that I was not quite tall enough to eat so much. Many of the crew spoke German and translated everything I needed to know. I learned English words like “chicken” and “fried potatoes” and “hamburger.” I ate corn and squash for the first time ever. While Mutti and Papa kept to their beds or were sick in our little toilet, I learned to say “please” and “thank you” in at least five languages.

With great fanfare, my new friends presented me with a foot-long toy U.S. army truck which I “drove” everywhere—the conquering military hero. I imagined victorious American soldiers riding under the khaki colored canvas top that covered the back of my truck. Crew members taught me to read the “U.S. Army” logo on each side of the cab. They gave me paper and pencil and had me print “United States of America.”

The body of my new truck was made of metal. The crew cautioned me to be careful of the sharp edges at the bottom of the truck. The doors of the cab were sealed shut but the tailgate was on a tiny hinge that allowed the back to open. I wished that I still had the lead soldiers I played with in Germany. They would fit into my truck and I could take them for rides. They surely would prefer riding to all the marching I had them do back in our Hannover apartment.

The halls of the ship were mostly empty because the sick passengers rarely left their rooms. That left great highways for my truck to travel. Together we turned corners, climbed stairs and explored every corner of the ship. Sometimes I couldn’t find my way back to our cabin. Then I looked for a member of the crew, knowing he would pick me up and carry me “home”—often finding an extra peppermint in his pocket. I felt loved by as many papas as any boy could ever want.

One day during lunch in the galley crowded with crew members, I reported that I was going to see the land of milk and honey. A few crew members warned me that I would not really find milk and honey on the streets—a huge disappointment because I believed everything my Papa told me. Nevertheless, they assured me that as long as I owned my American truck I would be safe and secure. They were quite correct.

Papa and Mutti had an argument as we entered New York Harbor—the first of many disagreements in our new homeland. We passed the Statue of Liberty at 4 a.m. on the 15th of November, 1939. My truck and I were sound asleep on my upper bunk bed. Papa insisted that he wake me to see the lady that welcomes all refugees. Mama said, “No, no. The boy needs his sleep.” Their quarrel woke me and Papa took me on deck.

Papa held me up to see THE STATUE, the symbol of liberty. With tears in his eyes he whispered some words in Hebrew that I recognized from the Passover Seder, “… and God brought you out of the Land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.”