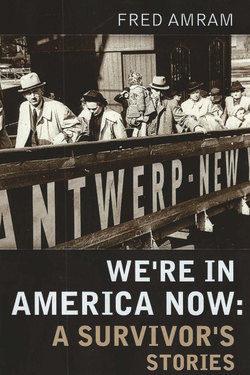

Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 19

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеXII. MY FIRST SEDER IN AMERICA

MUTTI DISLIKES HER JOB making fabric flowers in a factory. One day she describes to us how she twisted green paper around wire to make stems. On another day she reports that she attached yellow petals to green stems for the entire day. Her hands hurt. She hates work—any kind of work. “In the good days, before Hitler,” she tells me, “I didn’t have to work. Women of my class didn’t work.” She looks at my face, “Do you remember Grete? That was the maid who took care of you. When you napped, she cleaned the apartment. Then came Hitler and he took all that away.”

I do remember Grete, a skinny girl who lived with her parents in a Hannover suburb and had a long bus trip to and from our home in the center of town. One day I overheard a conversation between Grete and Mutti. There was some talk about how Christians could no longer work in Jewish factories, shops and homes. Grete never visited again. Instead we had those scary visits from the Gestapo.

Mutti often explains that she’s from a different class and hopes that soon she’ll be able to stop working. I’m a bit confused. Am I also different? Different from Papa? Papa loves to work.

Papa finds work in a bakery on the east side of Manhattan. It’s a long subway ride to and from the Strauss apartment in Washington Heights. Papa comes home covered with a white powder. He tells us that he breathes flour all day and that the ovens are hot and the bread smells good. Papa is happy to be working. Each Friday he receives an envelope filled with money—his pay for working. Mutti spends some of the money on groceries and Papa gives some to Mr. Strauss for rent. And Papa starts saving. One penny at a time. One day he will be self-employed again. He has a dream. He tells us about it at almost every dinner.

For Papa, the subway ride is a time to read. He picks up newspapers abandoned by other commuters. Papa’s fourth-grade education did not prepare him to be a sophisticated reader. And unlike Mutti, he had no courses in English. Like me, he has to sound out the letters and guess at the words. The subway is his classroom. And the newspapers help him keep up with events in Europe. After all, it’s the spring of 1940 and the European war is picking up momentum.

At the end of March, Papa is offered a second job. The bakery owns a tenement right next door. The manager has been unable to find a janitor. Would Papa like this opportunity? It would mean free rent and Papa could walk to the bakery.

On the first day of April, we move to the East Side with our few possessions and start buying a few pieces of furniture—used furniture when we can. The bakery manager is so happy to find someone to do this dirty work that he throws in a few dollars to help buy dishes and towels and a couch. The previous janitor left a huge brown icebox and a metal kitchen table with a bright red ring around the entire top surface. We buy four used straight-backed wooden chairs, perfect for our kitchen. They’re painted green to go with the paint on the kitchen wall.

Papa’s job as janitor is to take the garbage cans out each morning in time for the daily pick-up. Several times each week he mops the hallways and the steps from the third floor all the way down to the cellar. Mutti makes clear that she doesn’t mop floors or dust railings or touch other people’s garbage. However, with her modest English skills, she’s in charge of collecting rent and showing empty apartments to prospective English-speaking tenants. Thanks to the bookkeeping courses she had in high school, she becomes the bookkeeper for the building.

It is April 22, 1940, a warm spring day in New York City. We’re sitting in the kitchen of our first American apartment. The table is set for our first Passover Seder in the United States. No more Gestapo. No more hiding. No more fear.

Haggadah brought from Germany

We’ve lived in this dark, poorly ventilated New York tenement for just a few weeks. The kitchen has no window. However, if we leave the oversized door to the adjoining bathroom open, we can see the outside world from the kitchen table. The bathroom window looks out on a shaft of air surrounded by bricks and more windows. The courtyard, perhaps 30 feet square, allows for minimal light and fresh air. New York City is warm and humid this April. Sounds from many open windows echo in the three-story shaft. Neighbors have few secrets. Fights in the Hennessey household and parties at the Francos became public news. Laundry lines allow soot-gathering underwear to dry. Smells from courtyard trash containers waft into our first-floor apartment window.

I daydream often about our two-week long sea voyage that I spent mostly with crew. Perhaps I’ll become a sailor. Right now I’m thinking about the last morning when Papa held me up to see the Statue of Liberty. I remember that Papa talked about the meaning of the statue—about freedom and a new life and about the Promised Land.

Else Nussbaum (Omi)

We are free! An appropriate insight for our first American Passover. The Seder table looks festive with candles lit and almost-new Passover dishes provided by my Uncle Max, who came to the United States a year before we did. The prayer books, the Haggadah, the re-telling of the story of the exodus out of Egypt, came with us from the old country, traveling in my little suitcase. Each page is divided into two columns. The right column is printed in Hebrew and the left column shows a German translation. A few black-and-white pictures help stimulate my imagination.

Years later, when my maternal grandmother, my Omi, joins us for her first Seder in the States, she cries throughout the evening, mourning the many who will never again experience a holy day. Omi mourns for two of her daughters, their husbands and her granddaughter, all murdered by the Nazis. She mourns three brothers and a sister and their families, all butchered. She grieves for the dead and she is unable to celebrate this moment of life, this holiday of hope.

Tonight Papa feels festive and positive. He talks about our escape, father, mother and son, via Holland and Belgium and two weeks at sea. It had been a long, trying journey, an exodus out of slavery like that of Moses himself. Now we are celebrating freedom at the Seder table.

Mutti lights two candles and recites the appropriate blessings from memory. We all know the blessings for matzo and wine. In my embarrassed, childish voice, chanting in Hebrew, I recite the four questions asked by the youngest participant at every Seder throughout the world, now and in times long past. I begin, “Why is this night different from all other nights?”

“We were once slaves in Egypt.” Papa reads from the Haggadah.

In another part Papa reads, “You shall remind your son that he was once a slave in Egypt.” He asks me questions about what I remember of Germany and retells stories about our former life, lest I forget.

Every few minutes Mutti jumps up to stir something on the stove. It’s an old stove but Mutti has planned a special Passover dinner. She apologizes for what she believes to be a Spartan meal. “That’s all we can afford.”

Papa assures her that it will be fine. “Much better than any meal we had last year under the Nazis.”

I don’t recognize any of the smells. I’m very hungry.

Mutti has gathered the Passover symbols on a makeshift Seder plate. There is a lamb bone to remind us of the tenth plague—the killing of the Egyptian firstborn. “And the angel of death passed over the homes of the Hebrews.” Somehow Mutti translates that story into, “You, as the firstborn, have a great responsibility.” I’m more afraid of this unknown responsibility than of the angel of death.

Mutti has made charoses, a mixture of apples, nuts, red wine and spices. The charoses represents the mortar the Hebrew slaves were forced to use when they built structures for the Egyptians. Papa and I like the sweetness of the charoses and take several portions—but we only say the blessing once.

Papa tricks me into taking a large bite of the bitter herb that represents the bitterness of slavery. I chomp on the fresh horseradish root and almost immediately begin to cry. Mutti gives me a handkerchief to blow my runny nose and Papa gives me more charoses to cool my mouth. Mutti scolds Papa.

Papa, a small wiry man with a huge baritone voice, sings the prayers in Hebrew as though he were on stage. He sings with all the energy he can muster. This is, for him, a celebration. Five feet one inch tall. Not a millimeter more. Thin and muscular from slave labor in the Tiefbau—enforced road construction. No more than a fourth-grade education. Thirty-nine years old. Papa knows how to celebrate freedom.

Papa sings about Moses and the prophets and about freedom then and now. He sings prayers of gratitude to God in Hebrew and in German. This small man sings with a mighty voice.

“Shhh, shhh,” says my mother. “Shhh, the window is open. The neighbors will hear.”

My father rises from his chair and stretches to his full height. “I’ll sing as loud as I like,” he says in German. “Let them hear. WE’RE IN AMERICA NOW!”