Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

When I was younger, I could remember anything, whether it had happened or not; but my faculties are decaying now and soon I shall be so I cannot remember any but the things that never happened.

Mark Twain’s Autobiography

PAPA LIKED TO TELL how he met Mutti. In 1930, he and a friend each brought a girlfriend on a Sunday afternoon date to Café Kröpke in Hannover, Germany. Sometime before sunset, Papa and his friend traded dates. Papa claimed he took home the prettier girl—the woman who became my mother. One day when he wasn’t nearby, I asked Mutti how she met Papa. She told the same story—and allowed that Papa took home the prettier girl.

The story of how my parents met illustrates how I learned about many of the events in this book. For example, I write about my bris, my circumcision ceremony. Only eight days old at the time, clearly I don’t really remember the details. However, if Mutti and Papa separately told the same story and it was corroborated by my Uncle Max and my Aunt Beda, surely it must be true—or so I believe. And so, many events were told and retold around the dinner table until I can’t be sure what I remember and what I was told and only think I remember.

Do I tell the truth? Only as much as I am able. My favorite poet, Dylan Thomas, wrote in 1954, “I can never remember whether it snowed for six days and six nights when I was twelve or whether it snowed for twelve days and twelve nights when I was six.” Memory, Thomas and I agree, is unreliable.

Elderly Fred Amram

In Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, American author Mary McCarthy writes, “I remember we heard a nightingale together, on the boulevard near the Sacred Heart convent. But there are no nightingales in North America.” The “memory” becomes part of McCarthy’s memoir and we believe it even if the “memory” might have come from reading London-dwelling T.S. Eliot’s poem about the convent of the Sacred Heart. And so my perceptions are my perceptions. In a memoir one should not take liberties with the truth. This is my world as I believe it to be true—today.

I tell the truth as I remember events filtered through my feelings as a youngster and, again, filtered through the memory of a nostalgic old timer. Twice-baked potatoes. I have changed a few names to protect the innocent—or because my memory hit a blank.

And forgive me if I interrupt myself or become sidetracked. Isn’t that the way we tell a story? Ultimately the truth lies in the interruptions. Ask any psychiatrist.

As much as we like to generalize, each Holocaust survivor describes a unique experience. Each Auschwitz survivor tells a different story as does each survivor who spent the war in hiding or who, like me, was lucky enough to leave before the worst of times. This book tells my story and focuses, in part, on the events that led up to the worst of the genocide, led up to Auschwitz and the other death camps.

Every genocide creates displaced persons—refugees. All of us, no matter from which genocide we escaped, bring memories that shape our assimilation.

In this collection of stories—and it is a collection—I share my experiences and feelings as a child survivor. It is my truth of being an outsider, a Jew in Nazi Germany, and then a foreign Jew growing up in America, still an outsider—a stranger in a strange land.

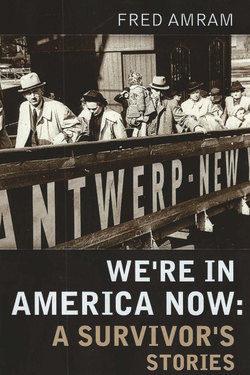

My life in Germany is written in the past tense. As I step off the boat I enter the present tense. What’s past is past and…