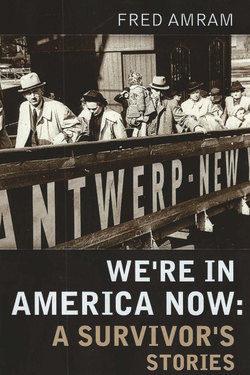

Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеII. THE CHANUKAH MAN

UNCLE MAX ALWAYS spent the first night of Chanukah with us. Our large apartment in Hannover had space for overnight guests. Uncle Max, Papa’s brother, was a bachelor living in Hamburg. He visited often. Like most bachelor uncles, he doted on his nephew—in this case his only nephew, an only child. Uncle Max was short like papa. However, unlike Papa who was thin and fit, even a little muscular, Uncle Max was round. After the Chanukah dinner and the lighting of the first candle and the singing of songs, Uncle Max lay on the couch, lit a cigar and relaxed. His round belly created a mountain on which my few lead soldiers could climb. Just when Uncle Max lit his cigar, my father announced that he had to go to the post office for business—weekday or weekend.

Even before Kristallnacht, Crystal Night, the night of broken glass, the Gestapo came to search Jewish homes. Sometimes they took the men with them. The men never returned. Later they came for the families, but in 1937 it was mostly men who disappeared. Papa was never home when the gruff uniformed men, with their “Heil Hitlers” and their pistols knocked on our door. He was out “on business”—perhaps he had gone to the post office—just as he was out each year on the first night of Chanukah.

And on the first evening of every Chanukah—every Chanukah before Kristallnacht—after the first candle was lit, the electric lights turned low and round Uncle Max on the couch blowing huge round clouds of cigar smoke, Papa announced that he needed to go to the post office for business. After a short while, a man with a deep voice would ring the doorbell. Mutti would let him in and announce with great surprise that the Chanukah man had come. He was wearing a hooded green Mackinaw which he never opened. I sat on this stranger’s lap, almost as frightened as when the Gestapo came to our house.

Papa’s childhood Chanukiah

“Have you been a good boy during the past year?”

I assured the Chanukah man that I had been as good as I could be—allowing some room for error. Uncle Max laughing aloud on the couch, with his jelly belly rocking, assured me that I was safe.

“Do you deserve coal for Chanukah?”

“No,” I whimpered. I was too well-behaved for that. In the end, the Chanukah man produced a small toy—once a lead ambulance that would ride on my uncle’s belly when we played together or on my blanketed legs when I was sick. And then the stranger was gone.

When Papa arrived home, I complained that he was always at the post office when the Chanukah man visited. Surely, I must have been the only Jewish boy in history who had a personal Chanukah man.

We arrived in New York City just before Chanukah of 1939, too poor to have a Chanukah that first year. Too poor even for a Chanukah man.