Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеVIII. WHAT’S IN A NAME?

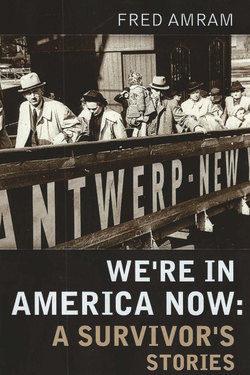

AS WE STEP OFF THE BOAT in New York harbor on that mid-November day in 1939, uniformed shepherds herd us into a cavernous warehouse. Frightened immigrants everywhere, confused and speaking their diverse European languages. A uniformed immigration official calls us to his desk to Americanize our names. We are to become a new breed, my father and I.

“Name?” asks the Gestapo-looking man pointing at me.

“Manfred Amram,” I whisper, looking up at Papa for protection.

We Amrams have traced our ancestors all the way back to the late seventeenth century. But back then we weren’t Amrams yet. Most German Jews were not allowed surnames until Napoleon conquered much of Europe in the very early nineteenth century. Until then Jews registered births in the neighborhood synagogue with Hebrew names. For example, my great-great-great-great grandfather Rabbi Judah was born in Abterode, Germany. In 1720, his father registered the new baby in the local shul, the neighborhood synagogue, as Judah ben Moshe, Judah son of Moses. Rabbi Judah did not have a secular surname. Rabbi Judah named his son, born in 1745, Moses to honor his father. The rabbi’s son then was named Moshe ben Judah. Moshe became a cantor and shochet, a ritual slaughterer, in Felsberg, Germany.

My Hebrew name is Moshe ben Menachem, Moses son of Menachem. My daughter’s name is Simcha bat Moshe, Joy daughter of Moses. Some modern Jewish families now also add the mother’s Hebrew name.

In about 1802, Napoleon, having conquered much of Europe, noticed that most German Jews did not have surnames. Jews traditionally were called Rabbi Judah, Butcher Abraham or Uncle Nachum. Napoleon decreed that Jews were to be permitted to select surnames and instructed the bureaucracy to implement that policy.

An official came to Cantor Moses ben Judah, my great-great-great grandfather, and declared, “The time has come for you to select a surname that your family can own forevermore. What shall it be?”

Cantor Moses was a learned man. He knew that in Exodus we read of the famous sister of Moses, Miriam, who, as the story goes, shipped her baby brother off in a basket. We also read of the brother of Moses, Aaron, who became his spokesman and who ultimately led the Jewish people into the Promised Land. We learn that the mother of Moses was Joacheb and no less than six times is it written in the holy book that Amram was the father of the Biblical Moses. All this Cantor Moses knew and decided that he too would be Moses, the son of Amram. Cantor Moses Amram now had an official surname.

Since that day, in every generation, the first born Amram son was given a name that begins with the letter “M” in honor of Cantor Moses Amram and in honor of the biblical Moses, son of Amram, who, it is written, led the Hebrews out of Egypt. And so it came to pass that my grandfather, Moritz Amram, begat a son named Max. Moritz, not wanting to deprive his second son of the “M” tradition, named my father, born in 1901, Meinhardt Amram. And Meinhardt had a son of his own and named him—me—Manfred.

Perhaps the Gestapo-looking man didn’t hear my frightened whisper. He asks again.

“Name?”

“Manfred,” I squeak in terror.

“Fred,” announces the official. He writes my new name in his record book. Then he prints my American name on my immigration papers.

The officer doesn’t seem to know that I need a name beginning with “M.” It’s my birthright. But I don’t complain. My frequent contact with the Gestapo has taught me never to disagree with a uniform.

Sitta’s (Mutti’s) identity card

“Name?” asks the uniformed man looking at Papa.

“Meinhardt,” answers my father.

“Milton” says the official and my father becomes an American.

“Name?” asks the uniformed man pointing at Mutti.

“Sitta,” answers my mother.

“Sara” says the tall, uniformed immigration official.

Mutti rants and cries. Under the Nazis, each German identity card assigned to Jewish men was stamped “Israel” and each document identifying Jewish women was stamped “Sara.” Israel and Sara were middle names assigned to all Jews and used as a pejorative. All German Jewish women were forced to use the same name, Sara. Mutti shouts that she might as well go to the concentration camp if she is to be renamed “Sara.” There is no consoling her. The official, a minor bureaucrat with no intent to do harm, writes “Sitta” in his book and on Mutti’s immigration papers. And so, Sitta, the most anti-German in the family, the one who argued for years that we should escape, the one who wants most to be American and who already speaks a little English, Sitta, retains her German identity.