Читать книгу We're in America Now - Fred Amram - Страница 20

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеXIII. A REFUGEE AT THE 1939-1940 NEW YORK WORLD’S FAIR

MUTTI’S ENGLISH, learned in high school, and the Wörterbuch, the Langenscheidt Dictionary she bought at a book store, gets us through life. She does the shopping, translates the signs at subway stations and helps Papa with the janitor’s paperwork.

When we move next to the bakery, I transfer to the local school’s kindergarten for the few weeks left in the school year. The change is difficult because a whole new group of children have to learn about my poor English skills and my funny accent.

Each morning Papa goes to work at the bakery. Each evening he brings home some rolls and news of the outside world. Only six months in America, we cannot afford a radio or newspapers. Papa’s co-workers share what news they know. Everyone is talking about the war in Europe. Each day Papa learns more English words from his co-workers. One evening each week Mutti and Papa go to the HIAS for a class where they learn English.

We sit around the dinner table, relishing our soup thickened with inexpensive vegetables from a pushcart on Second Avenue and supplemented by rolls covered with black dots. We always speak German at dinner. In response to my question about the black dots, Mutti explains, “These are called Mohnsamen,” using their German name.

“At the bakery,” Papa explains, “they are called ‘poppy seeds.’” Then he adds his little pun. “Let’s call them ‘Papa seeds.’”

“That’s silly,” says Mutti. I don’t think much of Papa’s puns either, but I like that he’s cheerful. Mutti’s conversation makes me feel that life is hard.

All through dinner, Papa picks up a few black dots from the oilcloth tablecover and swallows them. “Mmmmm, these ‘Papa’ seeds are tasty.”

One day at dinner Papa announces that he has news. In June he will take me to the World’s Fair. “At the bakery everyone is talking about the World’s Fair. During our break we looked at some photos in the Daily News. It looks spectacular and there are buildings from every country. Hardly anyone at work has been there because they can’t afford to go. But my son is going. It will be very educational.”

“My teacher has been to the World’s Fair,” I announce. “She went two times last summer and she tells us about it often. She says they have dangerous rides and food from many countries and people in costumes and …”

“That’s ridiculous,” Mutti grumps as she stands up to clear the table. Papa and I each grab an extra ‘Papa’ seed roll before they are put away. “That’s ridiculous,” Mutti repeats. “We barely have money for clothes. How can we afford entertainment?”

“It’s not entertainment,” Papa says quietly. “We won’t go on any rides and we’ll bring sandwiches from home. It will be educational. My foreman took his children and said they learned about the whole world. Freddy will learn about the whole world too. One day he will even graduate from a university.” Mutti has told me about doctors and lawyers who go to a university to learn stuff most people don’t know. I hate the responsibility Papa is placing on my shoulders, but a trip to the fair sounds exciting. I won’t worry about university just now.

Mutti allows that she had read about the New York World’s Fair when we were still in Germany. She says that big corporations have buildings there with science displays. I ask Mutti to explain the word “science.” She talks about chemistry and engineering using words I’ve never heard before like “Wissenschaft” and “Technik.” Mutti has read that many countries have art exhibitions. Mutti loves art and museums. She keeps reminding us that she is a highly cultured person.

“And Freddy will be highly cultured too.” And with that Papa closes the discussion.

Papa schedules three paid vacation days in late June of 1940, right after school is out. Weather permitting, we will go on Monday. Mutti has no vacation coming so she will have to work. Papa asks his workmates how to get to Flushing Meadows, the site of the fair.

It rains on Monday so we go on Tuesday. Mutti packs a lunch. Papa takes enough money for the subway ride, admission and drinks. He tells Mutti that he refuses to carry a thermos all day. Mutti makes him promise to bring home a few postcards with pictures of the fair.

Every day in every way I know that we’re poor. The children at school have toys. They have new shoes after Easter. They go to movies with their parents. They take the train to visit grandparents in the countryside. They show off how they break in their new baseball “mitts.” We can’t afford any of these things. But somehow Papa saved up the money for the World’s Fair. On the subway we talk about spending money. He tells me that food is most important. Then education for his son. Then giving to worthy causes. “Tikkun olam,” says Papa. “That’s Hebrew for ‘repair the world.’”

“That’s the Jewish way,” he adds.

When we finally arrive at the fair, we follow a long line of people toward a window. Papa buys our admission tickets. I hold them while Papa carefully puts his change into his pants pocket. “Someday soon I’ll buy a wallet,” he mumbles to himself. He’s wearing a dark gray suit and a white shirt. For Papa’s first birthday in America, last December, Uncle Max gave him a tie, the tie he’s wearing today. I’m wearing tan slacks and a green, long-sleeved dress shirt open at the collar.

I give our tickets to a uniformed man who directs us through a turnstile. We’re at the fair. Buildings tower, paths lead to other buildings and then to still more buildings. Signs are everywhere—in English. The Fair is huge and we are small. We hold hands all day. We hold tight. With the little English I’ve learned in six months of American schooling, I’m in charge of reading signs. Papa can sound out some words and we translate what we can. I often have to say, “I don’t know” when I really don’t understand. Pictures and imagination help our translations.

Papa explains that we’ve been to four countries: Germany, Holland, Belgium (for just a few days) and now we’re in the United States. We’re about to visit other countries. We step into a building representing Japan. I’ve never seen Japanese people. I like them. They’re short like Papa and me. We sit on the floor and drink tea. Papa explains that the people in Japan drink lots of tea. Mutti likes tea. Papa prefers coffee. I favor milk. A thin woman in a dress that reaches almost to the floor pours a second cup for Papa.

The Holland building shows off lots of paintings by famous Dutch artists. Lots of people in the building wear costumes just like in the paintings. Papa sees the word Palestine on a sign and rushes us to the Jewish Palestine building. We learn that the Jewish people want to build a homeland for the Jews. I worry that I will have to move again and learn still another language. Papa speaks Yiddish with several men. A woman gives me a flag and a map.

We view a typewriter display with machines old and modern. Papa explains what they do. He adds that if I ever want a typewriter of my own, I will have to know how to spell. And then I see a cow named Elsie, almost the same name as one of my grandmothers, Omi, still living in Germany. Mutti has been worried because we haven’t heard from her in a very long time.

Many of the buildings give away posters and picture postcards. We collect them all for Mutti. At a souvenir stand, Papa buys a little booklet of pictures to bring home.

We see a radio with pictures; it’s called “television.” We see a sleek train, several sporty cars, some art on a wall made with magically moving colored lights and a display showing what the future city will look like. I hope that one day I can fly the little airplanes that go straight up and down and sideways. We’re invited into a free air conditioned movie theatre. I can read the sign that says “cool air” and I feel the chill inside. The movie shows how a car is manufactured in a modern auto plant. I notice that “auto” in English and in German are the same. In the movie, I see lots of jobs that I want when I grow up.

Between us, Papa and I have had four and a half years of schooling. We don’t know much geography. Many of the exhibits—art and science—mystify us. And yet we’re inspired. Papa keeps saying, “This is what a peaceful world can be like.”

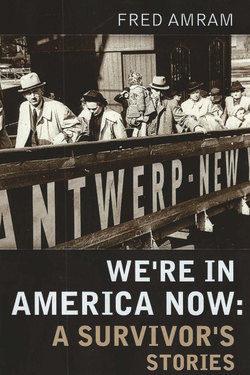

DuPont mural at 1939-’40 World’s Fair

Many large businesses have their own buildings where they show off what they manufacture and what they plan to create in the future. One such building has a huge mural two stories high. On the left side of this enormous picture is a scene showing a family from an earlier agricultural time. They struggle under the weight of hard work and poverty. On the right side of the great mural we see a family living in the new, industrial world of comfort and happiness. At the bottom of this mural is a banner with the words, “Better Things For Better Living Through Chemistry.” We translate “things” to “Dinge.” I can translate “Better Living” to “Besser Leben.” The German and English words sound alike. And from Mutti I learned that “Chemistry” is a science. I translate to “Wissenschaft” and “Technik.” I understand.

I promise Papa right then, at that moment, that I will study “Wissenschaft” (whatever that means) so that I can help create “better living.” Papa calls it “tikkun olam.” Repair the world.