Читать книгу Show Sold Separately - Jonathan Gray - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеFilm, Television, and Off-Screen Studies

A common first line for books on contemporary media, and for many a student essay on the subject, notes the saturation of everyday life with media. Certainly, my list of available cable channels seems to grow every month, while the list of movies in cinemas, on television, for rent, or available for purchase similarly proliferates at a precipitous rate. However, media growth and saturation can only be measured in small part by the number of films or television shows—or books, games, blogs, magazines, or songs for that matter—as each and every media text is accompanied by textual proliferation at the level of hype, synergy, promos, and peripherals. As film and television viewers, we are all part-time residents of the highly populated cities of Time Warner, DirecTV, AMC, Sky, Comcast, ABC, Odeon, and so forth, and yet not all of these cities’ architecture is televisual or cinematic by nature. Rather, these cities are also made up of all manner of ads, previews, trailers, interviews with creative personnel, Internet discussion, entertainment news, reviews, merchandising, guerrilla marketing campaigns, fan creations, posters, games, DVDs, CDs, and spinoffs. Hype and synergy abound, forming the streets, bridges, and trading routes of the media world, but also many of its parks, beaches, and leisure sites. They tell us about the media world around us, prepare us for that world, and guide us between its structures, but they also fill it with meaning, take up much of our viewing and thinking time, and give us the resources with which we will both interpret and discuss that world.

On any given day, as we wait for a bus, for example, we are likely to see ads for movies and television shows at the bus stop, on the side of the bus, and/or in a magazine that we read to pass the time. If instead we take a car, we will see such ads on roadside billboards and hear them on the radio. At home with the television on, we may watch entertainment news that hypes shows, interviews creative personnel, and offers “sneak peaks” of the making of this or that show. Ad breaks will bring us yet more ads and trailers, as will pop-ups or visits to YouTube online. Official webpages often offer us information about a show, wallpaper for our computer desktops, and yet more space for fan discussion, thereby supplementing the thousands of discussion sites run by fans or anti-fans. The online space also offers the occasional alternate reality game or particularly creative marketing campaign. Stores online and offline sell merchandise related to these films and shows, ranging from collectible Lord of the Rings (2001, 2002, 2003) “replica” swords or rings, to Dunder Mifflin t-shirts for The Office (2005–), to a talking Homer Simpson bottle opener. They sell licensed toy lines, linens, breakfast cereals, vitamins, and clothing to children. Bookstores and comic book shops sell spinoff novelizations and graphic novels. Game stores sell licensed videogames and board games. Fast food stores sell the Happy Meal or Value Meal. Music and video stores sell soundtracks, CDs of music “inspired by” certain films or shows, and DVDs and Blu-Ray discs rich with bonus materials, cast and crew commentaries, and extra scenes. Tour companies offer official Sex and the City (1998–2004) or Sopranos (1999–2007) tours of the New York area, while Lord of the Rings–themed tours of New Zealand are possible, and some fans lead themselves on their own tours of filming sites. Fans also write stories and songs and make films or vids about or set in film and television’s storyworlds. Film and television shows, in other words, are only a small part of the massive, extended presence of filmic and televisual texts across our lived environments.

Given their extended presence, any filmic or televisual text and its cultural impact, value, and meaning cannot be adequately analyzed without taking into account the film or program’s many proliferations. Each proliferation, after all, holds the potential to change the meaning of the text, even if only slightly. Trailers and reports from the set, for instance, may construct early frames through which would-be viewers might think of the text’s genre, tone, and themes. Discussion sites might then reinforce such frames or otherwise challenge them, while videogames, comics, and other narrative extensions render the storyworld a more immersive environment. In the process, such entities change the nature of the text’s address, each proliferation either amplifying an aspect of the text through its mass circulation or adding something new and different to the text. While purists may stomp their feet and insist that the game, bonus materials, or promos, for instance, “aren’t the real thing,” for many viewers and non-viewers alike the title of the film or program will signify the entire package. Individuals or communities will construct different ideas of what that package entails, based on their own interactions with its varying proliferations, and on their own sense of its textual hierarchy. But rarely if ever can a film or program serve as the only source of information about the text. And rather than simply serve as extensions of a text, many of these items are filters through which we must pass on our way to the film or program, our first and formative encounters with the text.

While many consumers deride the presence of hype and licensed merchandise as a nuisance, we also rely upon it, at least in part, to help us get through an evening’s viewing or a trip to the multiplex. Decisions on what to watch, what not to watch, and how to watch are often made while consuming hype, synergy, and promos, so that by the time we actually encounter “the show itself,” we have already begun to decode it and to preview its meanings and effects.

We are all familiar with the vernacular imperative to not “judge a book by its cover.” But we all do so nonetheless. Our world is heavily populated by promos and surrounding textuality, and these form the substance of first impressions. Today’s version of “Don’t judge a book by its cover” is “Don’t believe the hype,” but hype and surrounding texts do more than just ask us to believe them or not; rather, they establish frames and filters through which we look at, listen to, and interpret the texts that they hype. As media scholars have long noted, much of the media’s powers come not necessarily from being able to tell us what to think, but what to think about, and how to think about it.1 Mediated information and narratives are frames par excellence, trimming and editing the object of their attention for us with significant power and skill. Advertisers especially are charged with the task of creating frames for many of the items that surround us, harnessing semiotics and cultural scripts to frame everything from soft drinks to vacuum cleaners to back-pain medicine. They do so not simply by telling us to buy such products or services, but by creating a life, character, and meaning for all manner of products and services. Hype, in short, creates meaning. And by doing so, it regularly implores us to judge books by their glossy covers.

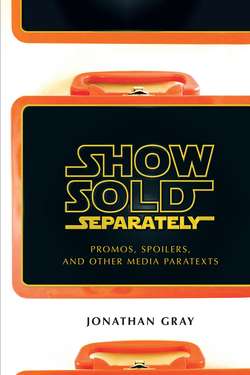

This book is about the machinations of those glossy “covers,” about how hype, synergy, promos, narrative extensions, and various forms of related textuality position, define, and create meaning for film and television. Promotion is vitally important in economic terms, of course, as a proper understanding of media multinational corporations’ strategies of synergy and multi-platforming tells us much about the political economy of the mass media. But for synergy to work, meaning must first be established; otherwise, why would one buy a Disney toy, get excited about a movie sequel or television spinoff, eagerly anticipate the release of a DVD or pod-cast, or trawl through the Internet for spoilers or vids? Why, too, might one spend significantly more time with such spinoff- or promo-related items than with the film or television show itself? Synergy works because hype creates meaning. Thus, this book represents an attempt to study how this meaning is created, and how it both relates to and in part constructs our understanding of and relationship with the film or television show. It is a look at how much of the media world is formed by “book covers” and their many colleagues—opening credit sequences, trailers, toys, spinoff videogames, prequels and sequels, podcasts, bonus materials, interviews, reviews, alternate reality games, spoilers, audience discussion, vids, posters or billboards, and promotional campaigns.

Consequently, the book argues for a relatively new type of media analysis. While engaging in close reading, audience research, and structural/political economic analysis of films and television programs, we must also use such techniques to study hype, synergy, promos, and peripherals. Charles Acland writes that “the problem with film studies has been film, that is, the use of a medium in order to designate the boundaries of the discipline. Such a designation assumes a certain stability in what is actually a mutable technological apparatus. A problem ensues when it is apparent that film is not film anymore.”2 This is also a problem with television studies, for, I would quibble with Acland, film has never been (just) film, nor has television ever been (just) television. Thus, while “screen studies” exists as a discipline encompassing both film and television studies, we need an “off-screen studies” to make sense of the wealth of other entities that saturate the media, and that construct film and television.