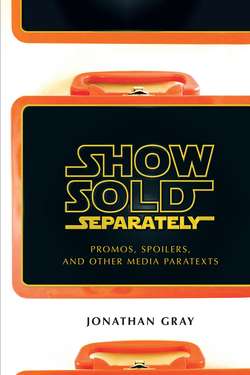

Читать книгу Show Sold Separately - Jonathan Gray - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Of Texts, Paratexts, and Peripherals: A Word on Terminology

ОглавлениеWe might begin by finding a single term to describe these various entities. Promos and promotion involve the selling of another entity. Or, stepping beyond “normal” levels of advertising is hype. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines “hype” as “extravagant or intensive publicity or promotion.” Hype is etymologically derived from “hyper-,” meaning “over, beyond, above” or “excessively, above normal,” which is in turn from the Greek “huper,” meaning “over, beyond.” The term alludes to advertisements and public relations, referring to the puffing up, mass circulation, and frenetic selling of something. Hype is advertising that goes “over” and “beyond” an accepted norm, establishing heightened presence, often for a brief, unsustainable period of time: like the hyperventilating individual or the spaceship in hyperdrive, the hyped product will need to slow down at some point. Its heightened presence is made all the more possible with film and television due to those industries’ placement—at least in their Hollywood varieties—within networks of synergy. Deriving from the Greek “sunergos,” meaning “working together,” synergy refers, says the OED, to “the interaction or cooperation of two or more organizations, substances, or other agents to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate effects.” Within the entertainment industry, it refers to a strategy of multimedia platforming, linking a media product to related media on other “platforms,” such as toys, DVDs, and/or videogames, so that each product advertises and enriches the experience of the other. And whereas hype is often regarded solely as advertising and as PR, synergistic merchandise, products, and games—also called peripherals—are often intended as other platforms for profit-generation.

All of these terms have their virtues. Promotion suggests not only the commercial act of selling, but also of advancing and developing a text. Hype’s evocation of images of puffing up, proliferation, and speeding up suggest the degree to which such activities increase the size of the media product or text, even if fleetingly. Synergy implies a streamlining and bringing together of two products or texts. Peripherals, meanwhile, suggest a core entity with outliers that might not prove “central” and that might not even be doing the same thing as that entity, but that are somehow related.

Although each of these terms has its utility in given instances, all have inherent problems. Hype is often regarded in pejorative terms, as excessive. In addition to its listing of “hype” as “extravagant,” for instance, the OED provides a second definition, as “a deception carried out for the sake of publicity,” while the verb form means “to promote or publicize (a product or idea) intensively, often exaggerating its benefits” (emphasis added). The term thereby evokes the image of an entity whose existence is illegitimate, inauthentic, and abnormal, when I will be arguing that hype is often mundane and business as usual. Hype, promotion, promos, and synergy are also all terms situated in the realm of profits, business models, and accounting, which may prove a barrier for us to conceive of them as creating meaning, and as being situated in the realms of enjoyment, interpretive work and play, and the social function of media narratives. To call such elements “peripherals,” meanwhile, is to posit them as divorced and removed from an actual text, discardable and relatively powerless, when they are, in truth, anything but peripheral. Moreover, hype, promotion, and promos usually refer only to advertising rhetoric, and synergy and peripherals only to officially sanctioned textual iterations. Thus, while fan and viewer creations may work textually in similar ways to hype, promotion, promos, synergy, and peripherals, they are nearly always unauthorized elements that are thus not covered by such terminology.

Throughout this book, then, while I will occasionally use the above terms as context deems appropriate, I will more frequently refer to paratexts and to paratextuality. I take these terms from Gerard Genette, who first used them to discuss the variety of materials that surround a literary text.3 A fuller definition of these terms will be offered in chapter 1, but my attraction to them stems from the meaning of the prefix “para-,” defined by the OED both as “beside, adjacent to,” and “beyond or distinct from, but analogous to.” A “paratext” is both “distinct from” and alike—or, I will argue, intrinsically part of—the text. The book’s thesis is that paratexts are not simply add-ons, spinoffs, and also-rans: they create texts, they manage them, and they fill them with many of the meanings that we associate with them. Just as we ask paramedics to save lives rather than leave the job to others, and just as a parasite feeds off, lives in, and can affect the running of its host’s body, a paratext constructs, lives in, and can affect the running of the text.

Paratexts often take a tangible form, as with posters, videogames, pod-casts, reviews, or merchandise, for example, and it is the tangible paratext on which I focus predominantly. However, I will also argue that other, intangible entities can at times work in paratextual fashion. Thus, for instance, while a genre is not a paratext it can work paratextually to frame a text, as can talk about a text (though, of course, once such talk is written or typed, it becomes a tangible paratext), and so occasionally I will examine these and other intangible entities within the rubric of paratextuality too.

I must also be clear from the outset that throughout this book, I use the word text in a particular fashion. I elaborate upon and justify this use in chapter 1, but early warning should be provided to those readers who are accustomed to calling the film or television program “the text” or, in relation to paratexts, “the source text.” To use the word “text” in such a manner suggests that the film or program is the entire text, and/or that it completes the text. I argue, though, that a film or program is but one part of the text, the text always being a contingent entity, either in the process of forming and transforming or vulnerable to further formation or transformation. The text, as Julia Kristeva notes, is not a finished production, but a continuous “productivity.”4 It is a larger unit than any film or show that may be part of it; it is the entire storyworld as we know it. Our attitudes toward, responses to, and evaluations of this world will always rely upon paratexts too. Hence, since my book argues that a film or program is never the entire sum of the text, I will not conflate “film” or “program” with “text.” When I call for an “off-screen studies,” I call for a screen studies that focuses on paratexts’ constitutive role in creating textuality, rather than simply consigning paratexts to the also-ran category or considering their importance only in promotional and monetary terms.

Nevertheless, the money trail might guide our initial foray into an off-screen studies, as an invigorated study of paratexts could address an odd paradox of media and cultural studies: while the industry pumps millions of dollars and labor hours into carefully crafting its paratexts and then saturates our lived environments with them, media and cultural studies often deal with them only in passing. How important are they? By late 2008, major studios were spending, on average, $36 million per film on marketing—a full third of the average film budget—while blockbusters could require considerably more. Smaller companies such as Lionsgate habitually spend up to two-thirds of their budget on marketing.5 Meanwhile, DVD sales and rentals handily eclipse Hollywood’s box office revenues, with, for instance, 2004 seeing $7.4 billion in rentals to theaters, yet $21 billion from home video.6 Even blockbusters and box office giants are seeing vigorous “competition” from DVDs; New Line’s $305.4 million of revenue for DVD sales of The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers (2002) in 2003, for example, fell just shy of the film’s huge yield at the box office.7 And cineplexes are also being rivaled by the videogame industry—some of whose biggest hits are film and/or television spinoffs.8 In the world of television, as Amanda Lotz records, American networks and cable channels devote substantial advertising space to hyping their own programs. Network television alone, for instance, foregoes an estimated $4 billion worth of ad time in order to advertise its programs, airing over 30,000 promos a year. In 2002, the old WB network accepted more ads from parent company AOL Time Warner than from any other advertiser, suggesting how one of the great economic benefits of conglomeration has been the ability to advertise on commonly owned channels.9 Add to this the potentially colossal sums that media corporations can earn from merchandising, licensing, and franchising (in addition to Lord of the Rings, think Disney, Star Wars [1977], or The Simpsons [1989–]), and paratextuality is not only big business, but often much bigger than film or television themselves. Janet Wasko cites estimates that the licensed children’s products market is valued at $132 billion, that licensed products in general generate more than $73 billion a year, and that movie-based games earned the major studios as much as $1.4 billion in 2001.10

And yet media, film, television, and cultural studies frequently stick solely to the films and television programs with a loyalty born out of habit. John Caldwell notes the film and television industries’ widespread devaluation of “below the line” workers as lesser than the “above the line” directors, producers, writers, and actors.11 Media studies, too, often risk a similar devaluation of those whose labor and creativity can be just as constitutive of the text as that of the above-the-liners. While this move is evident in the relative dearth of materials studying or even theorizing “below the line” work on films and television shows, it is similarly evident in the relative lack of attention paid to the semiotic and aesthetic value of the “below the line” paratext, or to its creators. Synergy is seen in terms of profits, but too rarely in terms of textuality, as something that creates sense and meaning, that is engaged with and interpreted as is the filmic or televisual referent, and that can ultimately create meaning for and on behalf of this referent. A key starting point for this book, then, is that if the film and television industries invest so heavily in previews, bonus materials, merchandise, and their ilk, so should we as analysts. It is time to examine the paratexts.