Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBrazil

Consider the old man whose eyes were cast downward, his hands shaking, his body skeletal. Family members had left him at Vita’s gate. I asked him his name even though the volunteers told me that he did not know it. He muttered, “Pedro,” and smiled. He also knew where he had once lived: “Charqueadas.” He then grabbed his throat. “Grrrahaaa . . . hhhrhrraaahhgrrrrss . . . ahhrgaaahgrqqaa . . .” I could not understand. It was not the absence of words but the speaking of nonwords.

Oscar and other volunteers told me that Pedro probably had throat cancer, although they did not know for sure. When they brought him to a nearby hospital, the doctors would not see him—a document was missing—and told him to return in three months. The clinic will not refuse to see him, but it will put him in line, make him return to schedule appointments, and when the doctors finally have time for Pedro, it will probably be too late. Then the clinic can claim, as it does with too many others, that nothing can be done.

The residents of Vita are not simply isolated individuals who, on their own, lost the symbolic supports for their existence. Rather, the abandonados are the carriers and witnesses of the ways in which the social destinies of the poorest and the sickest are ordered. The experience of individuals who live in such a dead space/language is traversed by the country’s structural readjustment, unemployment, malfunctioning public health system, and infamously unequal distribution of wealth.25

Historically, Brazil’s welfare system has been structured so that state intervention varies according to the segment of the population claiming social protection. “Citizenship” has been deemed universal for the minority who are rich, regulated according to market forces for the working class and the middle class, and denied to the multitudes who are poor and marginalized. According to Sônia Fleury, the “noncitizens” might be entitled to some minimum form of social assistance and charity in exchange for their votes—this is their “inverted citizenship” (quoted in Escorel 1993:35). Those occupying the upper strata of society not only live longer; their right to do so is ensured through bureaucratic and market mechanisms.

As I talked to city administrators, public health officers, and human rights activists, I was able to identify some of the institutional networks through which Vita emerged and was integrated into local forms of governance as well as some of the everyday practices that help to constitute the residents’ nonexistence. With the adoption of Brazil’s democratic constitution in 1988, health care had become a public right. “Health is a right of every individual and a duty of the state, guaranteed by social and economic policies that seek to reduce the risk of disease and other injuries, and by universal and equal access to services designed to promote, protect, and recover health,” stated the new Brazilian constitution (Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil 1988). The principles of universality, equity, and integrality within health services (Fleury 1997) were supposed to guide the new Brazilian health care system (Sistema ⁄nico de Saúde, or SUS). In practice, however, efforts to implement these principles collided with historically entrenched forms of medical authoritarianism (Scheper-Hughes 1992) and the realities of fiscal austerity, decentralization, and community- and family-centered approaches to primary care, amid the rapid encroachment of private health care plans. In 1989, for example, the federal government spent eighty-three dollars per person on health care, but in 1993 this amount plunged to only thirty-seven dollars (Jornal NH 1994b).

Many of the country’s discourses and practices of citizenship in the 1990s were related to guaranteeing the universal right to health care as the economy and the state underwent a major restructuring.26 The activism of mental health workers was exemplary (Tenorio 2002). They actively engaged in making laws that shaped the progressive closure of psychiatric institutions and their replacement by local networks of community- and family-based psychosocial care (Amarante 1996; Goldberg 1994; Moraes 2000).27 This deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill was pioneered in the state of Rio Grande do Sul (Porto Alegre is its capital), where it was well under way by the early 1990s. In reality, however, the demands and strategies of the mental health movement became entangled in and even facilitated local government’s neoliberalizing moves in public health: the mad were literally expelled from overcrowded and inefficient institutions, and little new funding was allocated for the alternative services that had been proposed.

On the one hand, this local psychiatric reform confirmed the role of the Workers’ Party as a representative of a novel politics of social inclusion—PT, the Partido dos Trabalhadores, was already in power in the capital. It also occasioned a few exemplary services that treated “citizens burdened by mental suffering” and realized, if all too partially, a socialized form of self-governance. On the other hand, it shifted the burden of care from state institutions to the family and communities, which failed to live up to their idealized representations in the reform movement’s discourse. People had to learn new techniques to qualify for services and to live with what were, by and large, the limitations of new ideologies and institutions. Increasing numbers of mentally ill people began to live in the streets, along with the other leftovers of the country’s unequal and exclusionary social project. Many ended up in places like Vita.

Everyday life in the 1980s and 1990s in that region was marked by high rates of migration and unemployment, the rise of a drug economy in the poorest outlying areas, and generalized violence (see Ferreira and Barros 1999). As police forces increasingly engaged in erasing signs of misery, begging, and informal economies from the city, pastoral and philanthropic institutions took up the role of caregiver, albeit selectively. Simultaneously, families frequently responded to the growing burdens posed by new responsibilities for care and narrowing employment options by redefining their functional scope and value systems. As a corollary to all these institutional, economic, and familial processes, unemployed health professionals began opening their own care centers (modeled after Vita) for patients who had welfare benefits or some remaining assets. Around 1976, some twenty-five “geriatric houses” operated in Porto Alegre (Bastian 1986). There are now more than two hundred, about 70 percent of which operate as clandestine businesses hosting the elderly, the mentally ill, and the disabled in the most problematic of conditions (Ferreira de Mello 2001; Comissão de Direitos Humanos 2000).

That so many are regarded as superfluous testifies to the further dissolution of the country’s moral fabric. The Brazilian middle class, for instance, has historically acted as a buffer between the elite and the poor, as both guardian of morality and advocate for progressive politics. But in the wake of the country’s democratization and fast-paced neoliberalization, this vein of moral sensitivity and political responsibility has been largely replaced by sheer contempt, sociophobia, or sporadic acts of charity like the ones that sustain Vita (Freire Costa 1994, 2000; Kehl 2000; Ribeiro 2000; Caldeira 2002).

The abandoned in Vita know of death, and, when listened to, they offer insights into its fabrication. Their abandonment is part of a larger human life-context—it was realized in many domestic and public sites and through intricate medical transactions coexisting with already entrenched strategies of nonintervention. It is this apparently unknown relation of letting die to the constitution of private lives and public domains that an ethnography of Vita helps to illuminate.28

“A man is no longer a man confined but a man in debt,” writes Gilles Deleuze as he elaborates his idea of the fate of anthropos within the development of late capitalism. Deleuze speaks of the erosion of disciplinary and welfare institutions and the concurrent emergence of new forms of control in affluent contexts—“controls are a modulation, like a self-transmuting molding continually changing from one moment to the next, or like a sieve whose mesh varies from one point to another” (1995:178). Family, school, army, and factory are increasingly “transformable coded configurations of a single business where the only people left are administrators” (181). He explains: “Open hospitals and teams providing home care have been around for some time. One can envisage education becoming less and less a closed site differentiated from the workspace as another closed site, but both disappearing and giving way to frightful continual training, to continual monitoring of workers-schoolkids or bureaucratic-students” (174, 175). According to Deleuze, “we’re no longer dealing with a duality of mass and individual. Individuals become ‘dividuals’ and masses become samples, data, markets, or ‘banks’” (180).

The market, however, keeps generating both wealth and misery, movement and immobility. “One thing, it’s true, hasn’t changed—capitalism still keeps three quarters of humanity in extreme poverty, too poor to have debts and too numerous to be confined: control will have to deal not only with vanishing frontiers, but with mushrooming shantytowns and ghettos” (Deleuze 1995:181). There are too many people to include them all in the market and its flows. The question of what to do with these surplus bodies, with no apparent value and no way to survive and prosper, is no longer at the core of sovereignty and its outmoded populist welfare rhetoric. Their destinies are now determined by a whole new array of networks, and, as formal institutions either vanish or face ruin and governmental distance is crystallized, the household is further politicized.

As I traveled throughout the country, I could see signs of Vita everywhere: death and dying in the midst of Brazil’s big cities, Vita as a social destiny. True, statistics were showing important improvements in areas such as infant mortality and literacy, and the Cardoso administration was experimenting with significant new forms of governmentality whereby patient groups could mobilize within the state and have their demands for life-extending treatments realized (AIDS programs are by far the most visible and successful story of the reforming state).29 But even though the poorest could now also access medication and basic medical care in local (and often poorly functioning) branches of the universal health care system, I found an immense distress among these individuals over lack of housing and jobs, safety, and growing police violence. People I interviewed conveyed an overall sense that they had failed their children and themselves.

José Duarte, his wife, and four little children lived in a hut made of plastic bags, on the outskirts of the northeastern city of Salvador. I met him at a breakfast meeting for the homeless that had been organized by a group of Catholic volunteers. José had come to get food for his family. They had been evicted from the city’s historic district, which was being remodeled as a tourist center.

“The government kicked us out. The little compensation they gave us was only enough to buy this little piece of land next to a swamp. I worked downtown, sold ice cream, but now it takes me two hours to get there by bus. Winter is tough. How can I make money? What will the children eat?” He began to weep.

“The kids are all sick; rain passes through the plastic. Who has health? Health nobody has. . . . Every day we are ill, all kinds of illnesses, it is never good. There is no medical aid. Only if one has money for the bus and gets in line early in the morning and waits till late at night. But then one loses the day of work. To waste time, that is all there is. At home, wasted, looking at the children, hungry, lacking sandals, clothing. . . . I am so enraged”—he had no words to account for his failed struggles as a worker and his desperation as a father.

“The government says it wants to help. But you end up talking to so many people in this and that office, signing forms—and they don’t get back to you. They don’t listen. They do nothing. They have made the life of the poor even more difficult. Only the president can solve the problem of Brazil. He is the only one who could do something. But people like me can’t talk to him, and he does not know what is happening in the city. The only way to reach the president’s ears is if I were to go to TV. But to be on TV, you must have resources, and we all have the same story that people don’t want to hear. To do what?”

José’s words echoed philosopher Renato Janine Ribeiro’s strong critique of Brazil’s political-economic culture: “In Brazil it is actually possible to imagine a discourse that aims at the end of the social in order to emancipate society.” The categories social and society do not pertain to the same people and worlds of rights: “social refers to the needy, and society refers to the efficient ones” (2000:21). State and marketing discourses transmit the conviction that society is active as economy and passive as social life. “The objects of social action are assumed not to be able to become an integral and efficient member of society” (22). In sum, according to Ribeiro, dominant discourses “have privatized society” (24).

José’s troubled existence was caught in ceaseless contact with governmental services, but to no avail. He knew quite well that he and his family were part of a repetitive machine that spoke a language of accountability, while in practice the citizen faced indifference and his voice was lost. Meanwhile, José has learned to use his anguish and subjectivity to evoke moral sentiments in order to procure at least minimal objective help, which is so desperately needed.

This is an example of what people still outside Vita and similar institutions must do in order to survive as they are driven further into poverty and despair: some twenty homeless persons, including children, invaded an abandoned zoological garden in a city near Porto Alegre in the late 1990s. The squatters made their rooms in the cages. “Luiz Carlos Apio is one of the new residents of the Zoo,” wrote the newsletter Jornal da Ciência. “He is handicapped and an unemployed auto worker. Luiz made his house in the place formerly set aside for the rabbits. In order to enter, he has to go through a small door no more than half a meter high” (Sociedade Brasileira para o Progresso da Ciência 1998:24). For those who have no money, social life is the physiological struggle to survive. This plight is intrinsic to an economy thriving on an image of action, efficiency, and modernity, concludes Ribeiro—“we live a kind of schizophrenia” (2000:24).

In the bodies of the abandoned—such as those residents of Vita—political and social forms of life and thereby subjectivity have literally entered into a symbiosis with death without those bodies belonging to the world of the deceased.30

Consider Clifford Geertz’s chilling reflections on the technically and politically engineered demise of the Yanomami people as well as on our own blindness to this modern form of life/disappearance: “Now that their value as control group, a (supposedly) ‘natural,’ genetically ‘ancestral population’—the ‘last major primitive tribe . . . anywhere on earth,’ is diminished or disappeared and the experiments upon them have ceased and the experimenters departed, what sort of presence in our minds, what sort of whatness, are they now to have? What sort of place in the world does an ‘ex-primitive’ have?” (2001:21, 22).

Vita is a place in the world for ex-humans. I use this concept reluctantly as I try to express the difficult truth that these persons have been de facto terminally excluded from what counts as reality. I first thought of the term “ex-human” as Catarina told me, “I am an ex,” and constantly referred to herself as an “ex-wife” and her kin as “my ex-family.” It is not that the souls in Vita have had their humanity and personhood drawn out and are now left without the capacity to understand, to dialogue, and to keep struggling. Rather, when I say ex-human, I want to highlight the fact that these people’s efforts to constitute their lives vis-à-vis institutions meant to confirm and advance humanness were deemed good for nothing and that their supposed inhumanness played an important role in justifying abandonment. In the end, too many people “too poor to have debts”—even perhaps too poor to have families—are reduced to struggling without being able to survive on their own. As an extension and a reflection of the country’s political-economic and domestic readjustments, zones of abandonment such as Vita emerge. They make the regeneration of the abandonados impossible and their dying imminent. Before biological death, there comes their social death.

Social death and mobilization of life coexist in Brazil’s political and medical institutions, and the process of making decisions about who shall die and who shall live and at what cost has increasingly become a domestic matter (Biehl 2004).31 Against an expanding discourse of human rights and citizenship, we are confronted with the limits of infrastructures that help to realize these rights, biologically speaking, but only on a selective basis. As the reality of Vita reveals, those incapable of living up to the new requirements of market competitiveness and profitability and related concepts of normalcy are included in the emerging social and medical orders only through their public dying—and as though these deaths had been self-generated.

By “self-generated,” I mean that these noncitizens remain by and large untouched by governmental and nongovernmental interventions and become partially visible in the public health system only when they are dying. Without legal identification, they are marked as “mad,” “drug addicts,” “thieves,” “prostitutes,” “noncompliant”—labels in which their personhood is cast and which are meant both to explain their dying and to blame them for it. In the end, no records of their individual trajectories remain. The families or neighbors who disposed of them are also not to be found. The overall poverty and the complex social and medical interactions that seem to have exacerbated infections and weakened immunity remain unaccounted for. Moreover, Vita’s environment is so charged that the sickest are constantly exchanging diseases with the mad, so to speak, leaving them no possibility but “to die each other.” I do not know precisely what I mean by this expression “to die each other,” but I have seen the complexity of what happens in Vita, both in institutional and experiential terms, and I struggle to understand the matter of dying and what makes life and death so intimate with one another. No one mourns the abandoned, cast into oblivion.

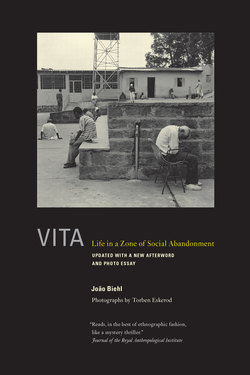

Unknown man, Vita 2001

Unknown woman, Vita 2001