Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

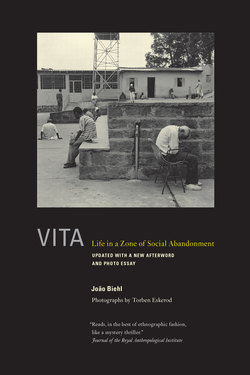

ОглавлениеBackyard, Vita 2001

Introduction

“Dead alive, dead outside, alive inside”

“In my thinking, I see that people forgot me.”

Catarina said this to me as she sat pedaling an old exercise bicycle and holding a doll. This woman of kind manners, with a piercing gaze, was in her early thirties; her speech was lightly slurred. I first met Catarina in March 1997, in southern Brazil at a place called Vita. I remember asking myself: where on earth does she think she is going on this bicycle? Vita is the endpoint. Like many others, Catarina had been left there to die.

Vita, which means “life” in Latin, is an asylum in Porto Alegre, a comparatively well-off city of some two million people. Vita was founded in 1987 by Zé das Drogas, a former street kid and drug dealer. After his conversion to Pentecostalism, Zé had a vision in which the Spirit told him to open an institution where people like him could find God and regenerate their lives. Zé and his religious friends squatted on private property near downtown, where they began a makeshift rehabilitation center for drug addicts and alcoholics. Soon, however, the scope of Vita’s mission began to widen. An increasing number of people who had been cut off from family life—the mentally ill and the sick, the unemployed and the homeless—were left there by relatives, neighbors, hospitals, and the police. Vita’s team then opened an infirmary, where the abandoned waited with death.

I began working with people in Vita in March 1995. At that time, I was traveling throughout several regions of Brazil documenting how marginalized and poor people were dealing with AIDS and how they were being integrated into programs based on new control measures. In Porto Alegre, I interviewed human rights activist Gerson Winkler, then coordinator of the city’s AIDS program. He insisted that I visit Vita: “It’s a dump site of human beings. You must go there. You will see what people do to people, what it means to be human these days.”

I had grown up in an area outside Porto Alegre. I had traveled through and worked in several poor neighborhoods in the north and south of the country. I thought I knew Brazil. But nothing I had seen before prepared me for the desolation of Vita.

Vita did not appear on any city map. Even though the existence of the place was acknowledged by officials and the public at large, it was not the concern of any remedial program or policy.

Winkler was right. Vita is the end-station on the road of poverty; it is the place where living beings go when they are no longer considered people. Excluded from family life and medical care, most of the two hundred people in Vita’s infirmary at that time had no formal identification and lived in a state of abject abandonment. For the most part, Vita’s staff consisted of residents who had improved their mental well-being enough to administer care to newcomers and to those considered absolutely hopeless. Lacking funds, training, and the proper equipment and medication, these volunteers were as ill prepared as the institution itself to deal with Vita’s residents.

Some fifty million Brazilians (more than a quarter of the population) live far below the poverty line; twenty-five million people are considered indigent.1 While in many ways a microcosm of such misery, Vita was distinctive in some respects. A number of its residents came from working- and middle-class families and once had been workers with families of their own. Others had previously lived in medical or state institutions, from which they were at some point evicted and thrown onto the streets or sent directly to Vita.

Despite appearing to be a no-man’s-land cut adrift, Vita was in fact entangled with several public institutions in terms of its history and maintenance. On many levels, then, Vita was not exceptional. Materially speaking, Porto Alegre contained more than two hundred such institutions, most of which were euphemistically called “geriatric houses.” These precarious places housed the abandoned in exchange for their welfare pensions; a good number of the institutions also received state funds or philanthropic donations.

I began to think of Vita and the like as zones of social abandonment.2

Catarina stood out from the others in Vita, many of whom lay on the ground or were crouched in corners, simply because she was in motion. She wanted to communicate. Adriana, my wife, was there with me. This is the story Catarina told us:

“I have a daughter called Ana; she is eight years old. My ex-husband gave her to Urbano, his boss. I am here because I have problems in my legs. To be able to return home, I must go to a hospital first. It is very complicated for me to get to a hospital, and if I were to go, I would worsen. I will not like it because I am already used to being here. My legs don’t work well. Since I got here, I have not seen my children.

“My brothers and my brother-in-law brought me here. Ademar, Armando. . . . I exercise . . . so that I might walk. No. Now I can no longer leave. I must wait for some time. I consulted a private doctor, two or three times. When it is needed, they also give us medication here. So one is always dependent. One becomes dependent. Then, many times, one does not want to return home. It is not that one does not want to. . . . In my thinking, I see that people forgot me.”

Later, I asked the volunteers whether they knew anything about Catarina. They knew nothing about her life outside Vita. I repeated some of the names and events Catarina had mentioned, but they said that she spoke nonsense, that she was mad (louca). She was a person apparently lacking common sense; her voice was annulled by psychiatric diagnosis. Without an origin, she had no destiny other than Vita.

I was left with Catarina’s seemingly disjointed account, her story of what had happened. As she saw it, she had not lost her mind. Catarina was trying to improve her condition, to be able to stand on her own feet. She insisted that she had a physiological problem and that her being in Vita was the outcome of various relations and circumstances that she could not control.

Catarina evoked these circumstances in the figures of the ex-husband, the boss, the hospitals, the private doctor, the brothers, and the daughter who had been given away. “To be able to return home, I must go to a hospital first,” she reasoned. The only way back to her child, now living with another family, was through a clinic. The hospital was on the way to a home that was no more.

But adequate health care, Catarina suggested, was impossible to access. While seeking treatment, she had learned about the need for medication. She also implied that medicine had worsened her condition. This form of care operated in Vita as well: “When it is needed, they also give us medication here.” She was referring to a pharmaceuticalization of disarray that made persons in Vita “always dependent.”

Something had made it impossible for Catarina to return home. But the desire was still there: “It is not that one does not want to.”

The reality of Vita and this initial encounter with Catarina left a strong impression on me. As I wrote my dissertation on the control of AIDS in Brazil (1999b), I was constantly reminded of the place of death in family and city life, and of this person who was thinking through her abandonment. Over the years, Vita and Catarina became key figures for me, informing my own thinking about the changing political and medical institutions and new regimes of personhood in Brazil’s urban spaces. The AIDS work I was chronicling included heroic governmental and nongovernmental attempts to contain the epidemic’s spread through daring prevention programs focused on safe sex and efforts to halt mortality by making AIDS therapies universally available. Along with this formidable work and the establishment of new institutions to care for vulnerable and poor populations not routinely slated for intervention, I also saw zones of social abandonment emerging everywhere in Brazil’s big cities—places like Vita, which housed, in inhuman conditions, the mentally ill and homeless, AIDS patients, the unproductive young, and old bodies.

Neither legal authorities nor welfare and medical institutions directly intervene in these zones. Yet these very authorities and institutions direct the unwanted to the zones, where these individuals are sure to become unknowables, with no human rights and with no one accountable for their condition. I was interested in how the creation of these zones of abandonment was intertwined with the realities of changing households and with local forms of the state, medicine, and the economy. I wondered how life-enhancing mobilizations for preventing and treating AIDS could take place at the same time that the public act of allowing death proliferated.

Zones of abandonment make visible realities that exist through and beyond formal governance and that determine the life course of an increasing number of poor people who are not part of mapped populations. I was struggling to make sense of the paradoxical existence of places like Vita and the fundamentally ambiguous being of people in these zones, caught as they are between encompassment and abandonment, memory and nonmemory, life and death.

Catarina’s exercise and her recollections, in the context of Vita’s stillness, stayed in the back of my mind. I was intrigued by the way her story commingled elements of a life that had been, her current abandonment in Vita, and the desire for homecoming. I tried to think of her not in terms of mental illness but as an abandoned person who, against all odds, was claiming experience on her own terms. She knew what had made her so—but how to verify her account?

As Catarina reflected on what had foreclosed her life, the degree to which her thinking and voice were unintelligible was not determined solely by her own expression—we, the volunteers and the anthropologist, lacked the means to understand them. Catarina’s puzzling language and desires required analytic forms capable of addressing the individual person, who, after all, is not totally subsumed in the workings of institutions and groups.

Two years passed. I had begun to do postdoctoral work in a program on culture and mental health. At the end of December 1999, I returned to southern Brazil to further observe life in Vita, fieldwork that was to result in the text for a book of photographs that Torben Eskerod and I were planning on life in such zones of abandonment.

With the recent availability of some government funds, Vita’s infrastructure had improved, particularly in the recovery area (as the rehabilitation center was called). The condition of the infirmary was largely unchanged, although it now housed fewer people.

Catarina was still there. Now, however, she was seated in a wheelchair. Her health had deteriorated considerably; she insisted that she was suffering from rheumatism. Like most of the other residents, Catarina was being given antidepressants at the whim of the volunteers.

Catarina told me that she had begun to write what she called her “dictionary.” She was doing this “to not forget the words.” Her handwriting conveyed minimal literacy, and the notebook was filled with strings of words containing references to persons, places, institutions, diseases, things, and dispositions that seemed so imaginatively connected that at times I thought this was poetry. These were some of the first excerpts I read:

Computer

Desk

Maimed

Writer

Labor justice

Student’s law

Seated in the office

Law of love-makers

Public notary

Law, relation

Ademar

Ipiranga district

Municipality of Caiçara

Rio Grande do Sul

. . .

Hospital

Operation

Defects

Recovery

Prejudice

. . .

Frightened heart

Emotional spasm

I returned to talk with her several times during that visit. Catarina engaged in long recollections of life outside Vita, always adding more details to what she had told me during our first meeting in 1997. The story thickened as she elaborated on her origin in a rural area and her migration to Novo Hamburgo to work in the city’s shoe factories. She mentioned having more children, fighting with her ex-husband, names of psychiatrists, experience in mental wards, all told in bits and pieces. “We separated. Life among two persons is almost never bad. But one must know how to live it.”

Again and again, I heard Catarina conveying subjectivity both as a battleground in which separation and exclusion had been authorized and as the means through which she hoped to reenter the social world. “My exhusband rules the city. . . . I had to distance myself. . . . But I know that when he makes love to other women, he still thinks of me. . . . I will never again step in his house. I will go to Novo Hamburgo only to visit my children.” She spoke elusively about giving and getting pleasure. At times, she began a train of associations that I could not follow—but at the end, she always brought her point home. Catarina was also writing nonstop.

I had not planned to work specifically with Catarina, nor had I intended to focus on the anthropology of a single person.3 But by our second meeting in 1999, I was already drawn in, emotionally and intellectually. And so was Catarina. She told me that she was happy to talk to me and that she liked the way I asked questions. At the end of a visit, she always asked, “When will you return?”

I was fascinated by what she said and by the proliferation of writing. Her words did not seem otherworldly to me, nor were they a direct reflection of Vita’s power over her or a reaction against it, I thought. They spoke of real struggles, of an ordinary world from which Catarina had been banished and that became the life of her mind.

Dentist

Health post

Rural workers’ labor union

Environmental association

Cooking art

Kitchen and dining table

I took a course

Recipe

Photograph

Sperm

. . .

To identify

Identification

To present identity in person

Health

Catholyric religion

Help

Understanding

Rheumatic

Where had she come from? What had truly happened to her? Catarina was constantly reflecting on her abandonment and physiological deterioration. It was not simply a matter of transfiguring or enduring that unbearable reality; rather, it allowed her to keep the possibility of an exit in view. “If I could walk, I would be out of here.”

The world Catarina recalled was familiar to me. I had grown up in Novo Hamburgo. My family had also migrated from a rural area to that city to look for a new and better life. Most of my fifty classmates in first grade at the Rincão dos Ilhéus public school had dropped out by the fifth grade to work in local shoe factories. I dreaded that destiny and was one of the few remaining who continued to sixth grade. My parents insisted that their children study, and I found a way out in books. Catarina made me return to the world of my beginnings, made me puzzle over what had determined her destiny, so different from mine.

This book examines how Catarina’s destiny was composed, the matter of her dying, and the thinking and hope that exist in Vita. It is grounded in my longitudinal study of life in Vita and in Catarina’s personal struggles to articulate desire, pain, and knowledge. “Dead alive, dead outside, alive inside,” she wrote. In my journey to know Catarina and to unravel the cryptic, poetic words that are part of the dictionary she was compiling, I also traced the complex network of family, medicine, state, and economy in which her abandonment and pathology took form. Throughout, Catarina’s life tells a larger story about the integral role places like Vita play in poor households and city life and about the ways social processes affect the course of biology and of dying.

Those early conversations with Catarina crystallized three problems I wanted to specifically address in our work together: how inner worlds are remade under the impress of economic pressures; the domestic role of pharmaceuticals as moral technologies; and the common sense that creates a category of unsound and unproductive individuals who are allowed to die. As Catarina elliptically wrote: “To want my body as a medication, my body.” Or, as she repeatedly stated: “When my thoughts agreed with my exhusband and his family, everything was fine. But when I disagreed with them, I was mad. It was like a side of me had to be forgotten. The side of wisdom. They wouldn’t dialogue, and the science of the illness was forgotten.”

According to Catarina, her expulsion from reality was mediated by a shift in ways of thinking and meaning-making in the context of novel domestic economies and her own pharmaceutical treatment. This forceful erasure of “a side of me” made it impossible for her to find a place in family life. “My brothers are hard-working people. For some time, I lived with Ademar and his family. He is my oldest brother; we are five siblings. . . . I was always tired. My legs were not working well, but I didn’t want to take medication. Why was it only me who had to be medicated? I also lived with Armando, my other brother. . . . Then they brought me here.”

I wanted to find out how Catarina’s subjectivity had become the conduit through which her “abnormality” and exclusion had been solidified. What were the various mediations by which Catarina turned from reality and was reconstructed as “mad”—what guaranteed the success of these mediations? As I understood it, new forms of judgment and will were taking root in that extended household, and these transformations affected suffering as well as people’s understanding of normalcy and the pathology that she, in the end, came to embody. Psychopharmaceuticals seem to have played a key role in altering Catarina’s sense of being and her value for others. And through these changes, family ties, interpersonal relations, morality, and social responsibility were also reworked.

Why, I asked Catarina, do you think that families and doctors send people to Vita?

“They say that it is better to place us here so that we don’t have to be left alone at home, in solitude . . . that there are more people like us here. . . . And all of us together, we form a society, a society of bodies.”

Catarina insisted that there was a history and a logic to her abandonment. As I tried to find out how her supposedly nonsensical thoughts and words related to a now vanished world and what empirical conditions had made hers a life not worth living, I found Clifford Geertz’s work on common sense illuminating. “Common sense represents the world as a familiar world, one everyone can, and should, recognize, and within which everyone stands, or should, on his own feet” (2000a:91). Common sense is an everyday realm of thought that helps “solid citizens” make decisions effectively in the face of everyday problems. In the absence of common sense, one is a “defective” person (91).

“There is something of the purloined-letter effect in common sense; it lies so artlessly before our eyes it is almost impossible to see” (2000a:92). That is unique to the anthropological endeavor: to try to apprehend these colloquial assessments and judgments of reality—that are more assumed than analyzed—as they determine “which kinds of lives societies support” (93). Work with Catarina helped to break down this totalizing frame of thought, which envelops the abandoned in Vita in unaccountability. After all, common sense “rests its [case] on the assertion that it is not a case at all, just life in a nutshell. The world is its authority” (93; my emphasis).

For me, Catarina’s speech and writing captured what her world had become—a messy world filled with knots that she could not untie, although she desperately wanted to because “if we don’t study it, the illness in the body worsens.” Geertz is well aware of the physiological dimensions of common sense. As stories about the real, he writes, common sense is first and foremost grounded in ideas of naturalness and natural categories (2000a:85).

In Catarina’s case, the soundness or unsoundness of her mind was the nature either presupposed by her kin and neighbors or mastered by pharmaceuticals and the scientific truth-value they bestow. Familial and medical de liberations over Catarina’s mental state and the actions that resulted made her life practically impossible, I speculated. Here, the familial and the medical, the mental and the bodily, must be perceived as existing on the same register: tied to a present common sense. Following the words and plot of a single person can help us to identify the many juxtaposed contexts, pathways, and interactions—the “in-betweenness”—through which social life and ethics are empirically worked out, that is, “to remind people of what they already know . . . the particular city of thought and language whose citizen one is” (Geertz 2000a:92).

During my 1999 visit, Catarina gave me her oral and written consent to be the subject of this work. I had no structured method in the beginning, other than continuing to return and engage Catarina on her own terms. She refused to be seen as a victim or to hide behind words: “I speak my mind. I have no gates in my mouth.” Clearly, it was not up to me to give her a voice; rather, I needed to find an adequate understanding of what was going on and the means to express it.4 The only way to the Other is through language. Language, however, is not just a medium of communication or misunderstanding but an experience that, in the words of Veena Das and Arthur Kleinman, allows “not only a message but also the subject to be projected outward” (2001:22).

In the essay “Language and Body,” Das (1997) observes that women who were greatly traumatized by the partition of Pakistan and India did not transcend this trauma—as, for example, Antigone did in classical Greek tragedy—but instead incorporated it into their everyday experience. In Das’s account, subjectivity emerges as a contested field and a strategic means of belonging to traumatic large-scale events and changing familial and political-economic constellations. Inner and outer states are inescapably sutured. Tradition, collective memory, and public spheres are organized as phantasmagoric scenes, for they thrive on the “energies of the dead” who remain unaccounted for in numbers and law. The anthropologist scrutinizes this bureaucratic and domestic machinery of inscriptions and invisibility that authorizes the real and that people must forcefully engage as they look for a place in everyday life. In her work on violence and subjectivity (2000), Das is less concerned with how reality structures psychological conditions and more with the production of individual truths and the power of voice: What chance does one have to be heard? What power does speaking have to make truth or to become action?

In Vita, one is faced with a human condition in which voice can no longer become action. No objective conditions exist for that to happen. The human being is left all by herself, knowing that no one will respond, that nothing will crack open the future. Catarina had to think of herself and her history alongside the fact of her absence from the things she remembered. “My family still remembers me, but they don’t miss me.” Absence is the most pressing and concrete thing in Vita. What kind of subjectivity is possible when one is no longer marked by the dynamics of recognition or by temporality? What are the limits of human thought that Catarina keeps expanding? As the work progressed, I tried to help Catarina reconnect with her family and access medical care. But I was faced at every step with the terminal force of reality. This terminal reality requires an anthropological name for its condition.

Why did I choose to work with Catarina and not someone else? She stood out in that context of annihilation; she refused to be reduced to her physical condition and fate. She wanted to engage, and I had a gut feeling that something important for life and knowledge was going on that I did not want to miss. Her words pointed to a routine abandonment and silencing, and yet, in spite of all the disregard she experienced, Catarina conveyed an astonishing agency. Once I found myself on her side, we were both up against the wall of language. Language was not a point of separation but of relating—and comprehension was involved.

The work we began was not about the person of my thoughts and the impossibility of representation or of becoming a figure for Catarina’s psychic forms. It was about human contact enabled by contingency and a disciplined listening that gave each of us something to look for. “I lived kind of hidden, an animal,” Catarina told me, “but then I began to draw the steps and to disentangle the facts with you.” In speaking of herself as an animal, Catarina was engaging the human possibilities foreclosed to her. “I began to disentangle the science and the wisdom. It is good to disentangle oneself, and thought as well.” This remark meant the world to me. I wanted this work to be of value to Catarina. Working with her, as she looked for a way back to a familiar world, was also an anthropological bildung for me. Yes, a pedagogy of fieldwork is hierarchical, but it is also mutually formative, as Paul Rabinow notes: “As it is hierarchical, it requires care; as it is a process, it requires time; and as it is practice of inquiry, it requires conceptual work” (2003:90).5

Here, anthropology had to do something more than simply approach the individual from the perspective of the collective. Treated as mad, Catarina was presumed to operate outside memory, and in fact there was no evidence whatsoever to determine whether Catarina’s recollections were true or false, no one nearby to confirm her accounts, no information available concerning her life outside Vita. How to enlarge the possibilities of social intelligibility that she had been left to resolve alone? I had to find ways to decipher the real in her life and her words and to relate those words back to particular people, domains, and events of which she had once been a part—an experience over which she had no symbolic authority.

An immense parceling out of the specific ways communities, families, and personal lives are assembled and valued and how they are embedded in larger entrepreneurial processes and institutional rearrangements comes with on-the-ground study of a singular Other. Still, there was always something in the way Catarina moved things from one register to the other—past life, Vita, and desire—that eluded my understanding. This movement was her own language of abandonment, I thought, and that forced my conceptual work to remain in suspense and open as well.

I visited Catarina many times over the past four years, seeing her last in August 2003. I listened intently as she carried her story forward and backward. In addition to tape-recording and taking notes of our conversations, I read the volumes of the dictionary she continued to write and discussed them with her. I greatly enjoyed working with Catarina—looking into her eyes; speaking openly of things one does not understand; searching and finding, with someone else, not a perfect form but the means of knowing. And one must also search for ways to make the knowledge of singularity and immediate history that one finds in the field contribute to the care of self and others (Rabinow 2003; Fischer 2003). Talking extensively to friends and colleagues about my conversations with Catarina led the study—and also Catarina and her writing—into new contexts and possibilities. I am thinking not solely of the force of her poetic imagination to reach other lives but also of the thoughtful ways in which some health professionals and administrators interacted with Catarina, with her social and medical condition, and with her critical thinking as this investigation progressed.

At times, I began to act like a detective, seeking out the concrete trajectory of Catarina’s exclusion from everyday life, the acceleration of her physiological deterioration, and the roots of her language-thinking. Taking Catarina’s spoken and written words at face value took me on a journey into the various medical institutions, communities, and households to which she continually alluded. With her consent, I retrieved her records from psychiatric hospitals and local branches of the universal health care system. I was also able to locate her family members—her brothers, ex-husband, in-laws, and children—in the nearby industrial town of Novo Hamburgo. Everything she had told me about the familial and medical pathways that led her into Vita matched the information I found in the archives and in the field. Through return visits, patience, proximity, the laborious production of data that was not meant to exist, and the thick description of a single life, a certain block of reality came into view.

In tracing Catarina’s passage through these medical institutions, I saw her not as an exception but as a patterned entity. That is, she was subjected to the typically uncertain and dangerous mental health treatment reserved for the urban working poor. Medical technologies were applied blindly, with little calibration to her distinct condition. Like many, she was assumed to be aggressive and thus was overly sedated so that the institution could continue to function without providing adequate care. The diagnoses she received varied from schizophrenia to postpartum psychosis to unspecified psychosis to mood disorder to anemia. I interacted with health professionals who had overseen her treatments as well as with human rights activists and administrators who were involved in efforts to reform these services. I was attempting to directly address the various circuits in which her intractability gained form, circuits that seemed independent of both laws and contracts (Zelizer 2005).

After talking to all parties in Catarina’s domestic world, I understood that, given certain physical signs, her ex-husband, her brothers, and their respective families believed that she would become an invalid, just as her mother had become. They had no interest in being part of that genetic script. Catarina’s “defective” body then became a kind of battlefield on which decisions were made within local family/neighborhood/medical networks, decisions about her sanity and ultimately about whether “she could or could not behave like a human being,” as her mother-in-law put it. Depersonalized and overmedicated, something stuck to Catarina’s skin—the life-determinations she could no longer shed.

But this work was not only about finding “the truth” of Catarina’s story. It also precipitated events. With the help of several doctors, we scheduled medical examinations and brain-imaging, and we discovered that Catarina’s cerebellum was rapidly degenerating. We then embarked on a medical journey to identify her ailment and determine what could be done to improve her condition. She was fighting time, and there was a real urgency about the knowledge being generated. As fieldwork linked Catarina to Vita, Catarina to her past, and her abandonment to her biology, it also occasioned Catarina’s reentrance, if all too briefly, into the worlds of family, medicine, and citizenship. These events in turn led to a familiarity with the machinery of social death in which Catarina was caught and an understanding of the effort it takes to create other possibilities. As the realpolitik of abandonment came into sharp relief, questions of individual and institutional responsibility were addressed in new and different ways.

As fieldwork came to a close, Oscar, one of Vita’s volunteers on whom I depended for his insights and care, particularly in regard to Catarina, told me that things like this research happen “so that the pieces of the machine finally get put together.” In our conversations and in her writing Catarina was constantly referring to matters of the real. Had I focused only on her utterances within Vita, a whole field of tensions and associations that existed between her family and medical and state institutions, a field that shaped her existence, would have remained invisible.6

Catarina did not simply fall through the cracks of these various domestic and public systems. Her abandonment was dramatized and realized in the novel interactions and juxtapositions of several social contexts. Scientific assessments of reality (in the form of biological knowledge and psychiatric diagnostics and treatments) were deeply embedded in changing households and institutions, informing colloquial thoughts and actions that led to her terminal exclusion. Following Catarina’s words and plot was a way to delineate this powerful, noninstitutional ethnographic space in which the family gets rid of its undesirable members. The social production of deaths such as Catarina’s cannot ultimately be assigned to any single intention. As ambiguous as its causes are, her dying in Vita is nonetheless traceable to specific constellations of forces.

Once caught in this space, one is part of a machine, suggested Oscar. But the elements of this machine connect only if one goes the extra step, I told him. “For if one doesn’t,” he replied, “the pieces stay lost for the rest of life. Then they rust, and the rust terminates with them.” Neither free from nor totally determined by this machinery, Catarina dwelled in the luminous lost edges of a human imagination that she expanded through writing. By exploring these edges alongside a hidden reality that kills, we have a way into present human conditions, ethnography’s core object of inquiry.

One reads many books and borrows from their languages to understand the world one lives in. One also takes them into the field, where their propositions might not always work that well but are nonetheless helpful in generating figures of thought. This is one of the many good things about anthropology and the knowledge it produces: its openness to theories, its relentless empiricism, and its existentialism as it faces events and the dynamism of lived experience and tries to give them a form. In this book, I integrate theory into the descriptions of what I found in my work with Catarina, the medical establishment, and her family. In a similar vein, I relate her ideas and writing to the theories that institutions applied to her (as they operationalized concepts of pathology, normality, subjectivity, and citizenship, for example) and to the general knowledge people had of her. Rationalities play a part in the reality of which they speak. They form part of what Michel Foucault calls “the dramaturgy of the real” (2001:160) and become integral to how people value life and relationships and “enact the possibilities they envision” for themselves and others (Rosen 2003:x). I want this book to convey the active embroilment of reason, life, and ethics—as human existences are shaped and lost—that fieldwork captures.

One set of ideas that I initially brought to this work and that I briefly explore here concerns a person’s “plastic power.” “I mean,” wrote Friedrich Nietzsche in The Use and Abuse of History, “the power of specifically growing out of one’s self, of making the past and the strange one body with the near and the present, . . . of healing wounds, replacing what is lost, repairing broken molds” (1955:10, 12). Rather than speaking of an essential individuality or of an all-knowing subject of consciousness, Nietzsche calls our attention to modifications in subjective form and sense vis-à-vis historical processes and the possibilities of establishing new symbolic relations to the past and to a changing world.

Such plasticity—whether we think of it as the capacity for being molded or the adaptability of an organism to changes in its environment—is a theme moving through readings of anthropology, psychoanalysis, psychiatry, and cultural history. It appears in the “allo-plastic” capacity of Sigmund Freud’s neurotic patients to alter reality through fantasy (in contrast to “auto-plastic” psychotics) (1959b:279); in Bronislaw Malinowski’s argument about the “plasticity of instincts” under culture (as an alternative to the notion of a mass psyche) (2001:216); in Marcel Mauss’s ensemble of the social, the psychological, and the biological, “indissolubly mixed together,” in “body techniques” (1979:102); in the intrasocial and intersubjective debate that Gananath Obeyesekere regards as the “work of culture” (1990); in Arthur Kleinman’s reading of patterns of social and moral upheaval in individual symptoms of distress (1981; Kleinman and Kleinman 1985); in Nancy Scheper-Hughes’s account of the medicalization of the bodily common sense of “nervoso” alongside hunger (1992); in the body of the old person becoming an “uncanny double” in the liminal space between households and the science of old age, as evidenced by Lawrence Cohen (1998:269); and in the self-empowerment afforded to the subjected by ambiguity, as Judith Butler (1997) argues in The Psychic Life of Power. The notion of the self as malleable material runs through these otherwise divergent arguments; it is central to our understanding of how sociocultural networks form and how they are mediated by bodily affect and the inner world.7

A related literature expands this theme of malleability, finding it not so much in particular persons as in the plasticity of reality as such—that is, synthetic frameworks mediate social control and recast concepts of a common humanity. Theodor Adorno, for example, politicizes Freud’s group psychology model and argues that the peculiarity of modern authoritarian ties lies not simply in the recurrence of primordial instincts and past experiences but in their “reproduction in and by civilization itself” (1982:122; my emphasis). According to Adorno, Nazi science and propaganda created new mechanisms of identification that bound German citizens together, and against outsiders, in a state of moral blindness. Modern subjective reassemblage goes hand in hand with rational-technical politics and state violence.

In “Colonial Wars and Mental Disorders,” Frantz Fanon (1963) identifies and critiques the colonized subjectivity of the Algerian people under French imperialism. From Fanon’s perspective, the locus of imperial control is not necessarily the political and economic institutions of the colonizer but the consciousness and self-reflective capabilities of the colonized.8 Subjectivity is a material of politics, the platform where the agonistic struggle over being takes place. He states: “Because it is a systematic negation of the other person and a furious determination to deny the other person all attributes of humanity, colonialism forces people it dominates to ask themselves the question, constantly, ‘In reality, who am I?’” (1963:250). Fanon’s answer is one of deconstruction: whose reality?

Fanon rethinks Freud’s characterization of psychotic experience as being cut off from reality and being incapable of achieving transference.9 Rather than excising the psychotic from the possibility of treatment, Fanon is concerned with the mechanisms by which the reality that the psychotic patient appears unable to grasp has been effected. In dealing with psychosis, Jacques Lacan also urges psychiatrists and psychoanalysts to question their own trust in the order of reality (1977:216), to halt diagnosis, and to let patients define their own terms.

“There is intuitive intelligence, which is not transferable by speech,” said a patient in a conversation with Lacan. “I have a great deal of difficulty in logifying. . . . I don’t know if that is a French word, it is a word I invented” (1980:27). We are here faced with the patient’s making of meaning in a clinical world that would rather assign such meaning (see Corin 1998; Corin, Thara, and Padmavati 2003). We are also faced with Lacan’s important insight (drawn not only from intellectualization but also from his psychoanalytic practice)10 that the unconscious is grounded in rationality and in the interpersonal dimension of speech: “It is something that comes to us from the structural necessities, something humble, born at the level of the lowest encounters and of all the talking crowd that precedes us . . . of the languages spoken in a stuttering, stumbling way, but which cannot elude constraint” (1978:47, 48). For Lacan, subjectivity is that failed and renewable and all too human attempt to access the truth of oneself.11 As I listened to Catarina, I saw a picture of social life emerging as agonizing and uncertain, as order and chaos, as it was actually lived.

Through and beyond subjective recollection and archival representations, my ethnographic work approached the stubborn (though ambiguous), concrete, and irreducible experience of Catarina’s being in relation to others, to what was at stake for them in her vanishing from reality, and to what counted for her now (Kleinman 1999; Das 2000). In her own words:

I know because I passed through it

I learned the truth

And I try to divulge what reality is

It was not a matter of finding a psychological origin (a thing I don’t think exists) for Catarina’s condition or solely of tracking down the discursive templates of her experience. I understand the sense of psychological interiority as being ethnological, as the whole of the individual’s behavior in relation to his or her environment and to the measures that define boundaries, be they legal, medical, relational, or affective. It is in family complexes and in technical and political domains, as they determine life possibilities and the conditions of representation, that human behavior and its paradoxes belong to a certain order of being in the world.12

How does one become another person today? What is the price one pays? How does this change in personal life become part of memory, individual and collective? By way of her speech, the unconscious, and the many knowledges and powers whose histories she embodies, there is the plastic power of Catarina as she engages all this and tries to make her life, past and present, real, both in thought and in writing.

In working with Catarina, I found Byron Good’s study of epidemic-like experiences of psychoses in contemporary Indonesia particularly illuminating (2001). While directing attention to how the experiences of acute brief psychoses are entangled with the country’s current political and economic turmoil, the ghostliness of its postcolonial history, and an expanding global psychiatry, Good emphasizes the ambiguities, dissonances, and limitations that accompany all attempts to represent subjectivity in mental illness. He suggests three analytic moves: the first, working inward through cultural phenomenology to discover how the person’s experience and meaning-making are woven into the domestic space and its forceful coherence; the second, bringing to the surface the affective impact and political significance of representations of mental illness and subjectivity; and the third, interpreting outward to the immediate economic, social, and medical processes of power involved in creating subjectivity.13 Good unremittingly resists closure in his analysis, challenging us to bring movement and unfinishedness into view.

As Catarina and I disentangled the facts of her existence, both the ordinariness of her abandonment and the ways it was forged in the unaccounted-for interactions of family, psychiatry, and other public services came into view. In the process, I also learned that the overpowering phenomenology of what is generally taken and treated as psychosis lies not in the psychotic’s speech (Lacan 1977) but in the actual struggles of the person to find her place in a changing reality vis-à-vis people who no longer care to make her words and actions meaningful. Catarina’s human ruin is in fact symbiotic with several social processes: her migrant family’s industrious adherence to new demands of progress and eventual fragmentation, the automatism of medical practices, the increasing pharmaceuticalization of affective break-downs, and the difficult political truth of Vita as a death script. Adopting a working concept, I began to think of Catarina’s condition as social psychosis. By social psychosis, I mean those materials, mechanisms, and relations through which the so-called normal and minimally efficient order of social formations—the idea of reality against which the patient appears psychotic—is effected and of which Catarina is a leftover.

Catarina was constantly recalling the events that led to her abandonment. But she was not simply trying to make sense of them and to find a place for herself in history, I thought. By going through all the components and singularities of these events, she was resuming her place in them “as in a becoming,” in the words of Gilles Deleuze, “to grow both young and old in [them] at once. Becoming isn’t part of history; history amounts only to the set of preconditions, however recent, that one leaves behind in order to ‘become,’ that is, to create something new” (1995:170–171). As Catarina rethought the literalism that made possible a sense of exclusion, she demanded one more chance in life.

This is a dialogic ethnography, and the book’s progression mirrors the progression of our joint work. Both Catarina’s efforts, as desperate as they were creative, to write herself back into people’s lives and the anthropologist’s attempts to support her search for consistency and demands for a possibility other than Vita are documented here. The narrative is constructed around my conversations with Catarina and the many people with whom we interacted as the study and related events unfolded—the other abandoned persons and the caretakers in Vita, Catarina’s extended family, public health and medical professionals, and human rights activists. I personally conducted all the interviews that compose the main body of the text and translated them to the best of my ability; they appear chronologically and have been edited only for the sake of clarity and conciseness.14 I wanted the book’s texture to stay as close as possible to Catarina’s words, to her own thinking-through of her condition, and to the reality of Vita, which envelops Catarina and her words.

Fieldwork and archival research further addressed the circuits and actions—the verbs, if you will—in which those words and thoughts were entangled, illuminating their worldliness and that of the social practices that affected Catarina. The book follows a logic of discovery. Throughout the narrative, I provide glosses on the history and scale of the various forces impinging on her abandonment. Just as I would like Catarina to talk to the reader, I also would like the reader to become increasingly intimate with the broader social terrain in which her destiny was configured as nonsensical and valueless. The book is written in a recursive mode, to convey the messiness of both the world and the real struggles in which Catarina and her kin were involved. At each juncture, a new valence of meaning is added, a new incident illuminates each of the lives in play. Long-term ethnographic engagement crystallizes complexity and systematicity: details, often dramatically narrated, reveal the nuanced fabric of singularities and the logic that keeps things the same. This ethnographic sense of ambiguity, repetition, and openness collides with my own sensibility in the way I have tried to portray the book’s main characters: as living people on the page, with their own mediated subjectivities, whose actions are both predetermined and contingent, caught in a constricted and intolerable universe of choices that remains the only source from which they can craft alternatives.

Tracking the many interconnections of Catarina’s life also allowed the tentative untangling of the puzzling strings of words that compose her dictionary, the book’s touchstone. The selection presented in Part Six is just a small sample of the richness of her creation. The more I learned of the literal conditions of Catarina’s life, the more I seemed able to decipher some of the raw poems in her writing. I hope that this ethnographic rendering of Catarina and her life will also help the reader to hear the desperation lying within her words and to respond to her unique capacity to transfigure that desperation into a form of art.

As the ethnographer and interpreter, I am always present in the account. Every time I went one step further in knowing Vita and Catarina and their symbiotic world, I was faced with anthropology’s unique power to work through juxtaposed fields and particular conditions in which lives are—concurrently, as it were—shaped and foreclosed. I find this ethnographic alternative to be a powerful resource for building social theory. The book weaves various theoretical debates through the human and ethnographic material. Throughout the book, as layers of subjectivity, reality, and theory open up, the figure and thought of Catarina provide critical access to the value systems and often invisible machineries of making lives and allowing death that are indeed at work both in the state and in the home. The book thus also represents the anthropologist’s ethical journey: identifying some of the ordinary, violent, and inescapable limits of human inclusion and exclusion and learning to think with the inarticulate theories held by people like Catarina concerning both their condition and their hope.

Vita is a progressive unraveling of the knotted reality that was Catarina’s condition—misdiagnosis, excessive medication, complicity among health professionals and family members in creating her status as a psychotic—and the discovery of the cause of her illness, which turned out to be a genetic and not a psychiatric condition. It charts the domestic events and institutional circumstances through which she was rendered mentally defective and hence socially unproductive and through which her extended family, her neighbors, and medical professionals came to see the act of abandonment as unproblematic and acceptable. Psychopharmaceuticals used to “treat” Catarina mediated the cost-effective decision to abandon her in Vita and created moral distance. Zones of abandonment such as Vita accelerate the death of the unwanted. In this bureaucratically and relationally sanctioned register of social death, the human, the mental, and the chemical are complicit: their entanglement expresses a common sense that authorizes the lives of some while disallowing the lives of others.

Catarina embodies a condition that is more than her own.15 Her life force was unique, but the human and institutional intensities that shaped her destiny were familiar to many others in Vita. In the dictionary, Catarina often referred to elements of a political economy that breaks the country and the person down and to herself as being out of time:

Dollars

Real

Brazil is bankrupted

I am not to be blame

Without a future

By tracking the social contexts and exchanges in which Catarina’s abandonment and pathology took form, this book reflects on the political and cultural grounds of a state that keeps playing its part in the generation of human misery and a society that forces increasingly larger groups of people considered valueless into such zones, where it is virtually guaranteed that they will not improve. The book demonstrates that, through the production of social death, both state and family are being altered and their relations reconfigured. State and family are woven into the same social fabric of kinship, reproduction, and death. Catarina’s body and language were overwhelmed by the force of these processes, her personhood unmade and remade: “Nobody wants me to be somebody in life.”

In many ways, Catarina was caught in a period of political and cultural transition. From his inauguration in 1995, President Fernando Henrique Cardoso worked toward state reform that would make Brazil viable in an inescapable economic globalization and that would allow alternative partnerships with civil society to maximize the public interest within the state (Cardoso 1998, 1999).16 But in the process and on the ground, how are people, particularly the urban poor, struggling to survive and even prosper? And what is happening to the polity and social relations?

Scholars of contemporary Brazil argue that the dramatic rise in urban violence and the partial privatization of health care and police security have deepened divisions between the “market-able” and the socially excluded (Caldeira 2000, 2002; Escorel 1999; Fonseca 2000, 2002; Goldstein 2003; Hecht 1998; Ribeiro 2000). All the while, newly mobilized patient groups continue to demand that the state fulfill its biopolitical obligations (Biehl 2004; Galvão 2000). As economic indebtedness, ever present in the hinterland, transforms communities and revives paternalistic politics (Raffles 2002), for larger segments of the population, citizenship is increasingly articulated in the sphere of consumer culture (O’Dougherty 2002; Edmonds 2002). An actual redistribution of resources, power, and responsibility is taking place locally in light of these large-scale changes (Almeida-Filho 1998). Overburdened families and individuals are suffused with the materials, patterns, and paradoxes of these processes, which they are, by and large, left to negotiate alone.

The family, as this ethnography illustrates, is increasingly the medical agent of the state, providing and at times triaging care, and medication has become a key instrument for such deliberate action.17 Free drug distribution is a central component of Brazil’s search for an economic and efficient universal health care system (a democratic gain of the late 1980s). Increasing calls for the decentralization of services and the individualization of treatment, exemplified by the mental health movement, coincide with dramatic cuts in funding for health care infrastructure and with the proliferation of pharmaceutical treatments. In engaging with these new regimes of public health and in allocating their own overstretched and meager resources, families learn to act as proxy psychiatrists. Illness becomes the ground on which experimentation and breaks in intimate household relations can occur. Families can dispose of their unwanted and unproductive members, sometimes without sanction, on the basis of individuals’ noncompliance with their treatment protocols. Psychopharmaceuticals are central to the story of how personal lives are recast in this particular moment of socioeconomic transformation and of how people create life chances vis-à-vis what is bureaucratically and medically available to them.18 Such possibilities and the fore-closures of certain forms of human life run parallel with gender discrimination, market exploitation, and a managerial-style state that is increasingly distant from the people it governs.

I need to change my blood with a tonic

Medication from the pharmacy costs money

To live is expensive

The fabric of this domestic activity of valuing and deciding which life is worth living remains largely unreflected upon, not only in everyday life, as Oscar, the infirmary coordinator, mentioned, but also in the literature on transforming economies, states, and civil societies in the contexts of democratization and social inequality. As this study unfolded, I was challenged to devise ways to approach this unconsidered infrastructure of decision-making, which operates, in Catarina’s own words, “out of justice”—that is, outside the bounds of justice—and which is close to home. Fieldwork reassembled the decision-making process at various points and in various public interactions.

This ethnography makes visible the intermingling of colloquial practices and relations, institutional histories, and discursive structures that—in categories of madness, pharmaceuticals, migrant households, and disintegrating services—have bounded normalcy and displaced Catarina onto the register of social death, where her condition appears to have been “self-generated.” Throughout this chain of events, she knows that the verb “to kill” is being conjugated; and, in relation to her, the anthropologist charts and reflects on what makes this not only possible but ordinary. This is also, then, a story of the methodological, ethical, and conceptual limits anthropology faces as it goes into the field and tries both to verify the sources of a life excluded from family and society and to capture the density of a locality without leaving the individual person and her subjectivity behind.

From the perspective of Vita and from the perspective of one human life deemed mad and intractable, one comes to understand how economic globalization, state and medical reform, and the acceleration of claims to human rights and citizenship coincide with and impinge on a local production of social death. One also sees how mental disorders gain form at the personal juncture between the afflicted, her biology, and the technical and political recasting of her sense of being alive.

How to restore context and meaning to the lived experience of abandonment? How to produce a theory of the abandoned subject and her subjectivity that is ethnographically grounded?

Catarina is subjected

To be a nation in poverty

Porto Alegre

Without an heir

Enough

I end

In her verse, Catarina places the individual and the collective in the same space of analysis, just as the country and the city also collide in Vita. Subjection has to do with having no money and with being part of an imaginary nation gone awry. The subject is a body left in Vita without ties to the life she generated with the man who, as she states, now “rules the city” from which she is banished. With nothing to leave behind and no one to leave it to, there remains Catarina’s subjectivity—the medium through which a collectivity is ordered in terms of lack and in which she finds a way to disentangle herself from all the mess that the world has become. In her writing, she faces the limits of what a human being can bear, and she makes polysemy out of those limits—“I, who am where I go, am who am so.”

Catarina’s subjectivity is discovered in her constant efforts to communicate, to remember, to recollect, and to write—that is, to preserve something unique to her—all of which take on new and special import in the zone of abandonment where she and I encountered each other. In a place where silence is the rule, and the voices of the abandoned are regularly ignored, where their bodies are politically useful only in the publicity of their dying, Catarina struggled to transmit her sense of the world and of herself, and in so doing she revealed the paradox and ambiguity of her abandonment and that of others. The human condition here challenges analytic and political attempts to ground ethics or morality in universal terms, or in the exceptions who stand outside the system. As I had to grapple with the ways Vita creates a humanity caught between visibility and invisibility and between life and death—something I came to call, sadly, the ex-human—I also had to find ways to support Catarina’s efforts to make feasible her own way of being.

In Vita, then—beyond kinship, the right to live, and the taboo against killing—emerges the social figure of Catarina. Her language, bordering on poetry, autopsies the human and grounds an ethics:

The pen between my fingers is my work

I am convicted to death

I never convicted anyone and I have the power to

This is the major sin

A sentence without remedy

The minor sin

Is to want to separate

My body from my spirit

The book brings forth the reality that hides behind this “I,” coming to a final line in Vita. It also transmits the struggle to produce a dialogic form of knowledge that opens up a sense of anticipation in this most desolate environment. How can the anthropological artifact keep the story moving and unfinished?

Vita 1995

Vita 1995

Vita 1995

Vita 1995

Vita 1995

Vita 1995

Vita 1995