Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 16

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеEx-Human

“I finished writing the book you gave me,” Catarina reported when we met again in early August 2000. “I left the book in the pharmacy with Clóvis, the nurse, but he threw it away. I was sad. I kept thinking that one day João and Adriana will come back, and they will want to read the book, and I don’t have it anymore.” I told Catarina I trusted that her writing would resume. She then confided: “Clóvis and I are dating.”

She quickly changed the subject: “My little suitcase was also thrown away. The volunteers said that it was getting moistened.”

I handed Catarina another empty notebook. She smiled, with a seemingly sedated face: “I have been at a standstill. . . . My head was full, full of nonsense. . . . So I stopped writing.”

“My gums are inflamed. It aches a lot. Clóvis told me that they would take me to the dentist.” Catarina added that he was giving her vitamins and pills, a white and a blue one, for pain. “Clóvis gives medication to each one of us. He puts the pills in the little cups with our names and the dose, the right dose . . . and distributes it to all of us.” Catarina looked very tired.

How did you sleep?

“I woke up in the middle of the night because of Lili, my bedmate. She talks in her sleep. It took me a long time to fall asleep again.”

Do you recall any dreams you had?

“I dreamed that I was . . . no . . . suddenly a man came and hit me and pulled my hair. I don’t know. I felt bad and began to scream, asking for help. Then Lili was there. I don’t recall more. It was a nightmare.”

It sounded like it had really happened, I thought. I asked whether she had recognized the man in the dream, but she said she had not.

I mentioned that sometimes, after waking from a dream, I would scribble down the things I recalled.

“Yes,” she replied, “dreams help us to understand the fears we have. A nightmare can also be a desire. If one doesn’t study what one has dreamed, then the dreams stay in the life that was dreamed. And, as one returns to life, one keeps thinking that everything is normal.”

I was confused. Are you saying, I asked, that if we don’t interpret a dream, then the dream stays present during the day, as if we lived in a dream-state?

“No, that’s not what I am saying. A little remnant of the dream is transmitted to us . . . the rest is up to us to channel and decipher. If we don’t decipher, we will not be able to remember what actually happened, what was and what wasn’t.”

What was and what wasn’t. In Catarina’s conception, the workings of the unconscious did not simply substitute for reality.34 Rather, the unconscious seemed to be a storehouse of ciphers that one must assemble and decode in order to understand what actually happened—the truth of losing one’s way of being in the world.

A cipher is an arithmetic symbol—zero—of no value by itself, used to occupy a vacant place in decimal numeration. A cipher is a person or thing that fills a place but is of no importance, a nonentity. A cipher is also a secret or disguised system of writing, a code used in writing; or a message written in this manner; or a key to such a system.

According to Catarina, that which truly happened continues to exist in the lost and valueless, in nonentities such as herself. Our grammars, George Steiner writes, make it difficult, even unnatural, to phrase a radical existential negativity, “but the failure of the human enterprise makes the doubt inescapable” (2001:39).

How did you learn to decipher your dreams?

“By myself,” answered Catarina, “when I was little. As I woke up, I kept thinking about what I had seen in the dream. I kept it to myself. I learned that it is good to dream, to think, the mind . . .”

But the time came when the borderline between the I and the Other had to be drawn more clearly. The fragile and forceful birth of writing and of the social person was what she described next.

“My father, he taught me the alphabet. We sat at the kitchen table, and he wrote ‘a,’ ‘b,’ ‘c’ in my notebook. I had to memorize the letters. But at first they didn’t stay in my mind. My father kept saying, ‘Catarina, you must keep this in your mind. If not, you will know nothing, and you won’t be a person.’ It was difficult. I wept a lot, but I learned the a, the b, and the c.”

That is what her dead father, she said, had left her with. A vital supplement, I thought.

Without knowing why, I changed the subject. Reminding Catarina that she had once told me that the doctors could not understand her pain, I asked her when she had first visited a doctor. She took my question literally, not letting me divert the conversation from where her thinking was taking it: “I think I was five years old. . . . I came down with something on my body that itched a lot. So my father took me to the pharmacist, and I healed. As a child, I only went to pharmacies. Real doctors who wrote prescriptions, that was later, the psychiatrists.”

She was telling me more than I could comprehend at the time about a painfully learned symbolic order and a personhood, both of which were no longer of any value (like her discarded book). As she alluded to them, the pharmaceutical identifications were another kind of writing that seemed to stand for her estrangement from the world.

“My ex-husband first took me to the psychiatrist, Dr. Gilson, in Novo Hamburgo, for him to help me, to discover the illness. But he lied to the doctor, saying that I was aggressive, that I beat the children. I got so mad that I actually hit him in front of the doctor. The doctor only prescribed. The nurse gave me an injection. I always had some medication to take. They said that they wanted to heal me, but how could they if they did not know the illness? . . . If I will count on doctors to tell me what I feel, I will remain incapacitated, because they don’t know the reason of what I am, of my illness, of my pain. They don’t know a thing.”

At that point, a woman who had been observing us for a while at a distance finally approached.

“This is my friend Lili,” said Catarina. “She speaks at night.”

“Yes, I am her friend,” replied Lili, looking straight into my eyes, with a wide-open smile and a copy of the New Testament in her hands.

Before I could ask Lili anything, she asked me: “Do you know what ‘not to live by the desire of the flesh any longer’ means?”

Stunned by her question, I failed to answer. I stayed on the surface of her words and mentioned that, as far as I knew, this was a statement by the Apostle Paul and that I would look into it further. I asked Lili where she was from, a question I grew up learning to ask in that world where mobility, both geographic and social, was all too rare.

“I am from Canoas, but now I am living here. I used to be Catholic, but then I converted to the Assembly of God. I used to leave home and run to the church. My husband hit me. I lived in the streets for some time, but then I went to live with my son. My son brought me here. My daughter-in-law wanted to kill me. I did nothing wrong. She called him ‘daddy,’ and I told her that I did not like that. She then tried to kill me with a kitchen knife.”

I was again faced with a condensed account of what the “mad person” thought had happened to her in life. I had heard similar accounts from Catarina when I first met her in 1997 and from Iraci during my previous visit. In their initial statements, all three had described being banned from the family and suffering the rupture of relations as well as the dangerous and now impossible desire for homecoming. These were not illness narratives channeling a search for meaning (Kleinman 1988; Good 1994; Mattingly 1998). Nor were they the “schizophrenic recording codes” that Deleuze and Guattari saw as opposing or simply parodying social codes, “never giving the same explanation from one day to the next” (1983:15). Neither were they the “diffuse and external rain of distractions” that marked the being-in-the-world of the homeless in the Boston shelter chronicled by Robert Desjarlais (1994:897).

As I came to realize over time, the accounts of many of the so-called mad in Vita were not ever-shifting. Rather, these narratives maintained an impressive steadiness and contextuality (as I would learn by tracking Catarina’s history), in spite of caretakers’ repeated insistence that they were “nonsense.” Instead of seeing these condensed accounts as proof of “a retreat from the world” (Desjarlais 1994:897), I began to think of them as pieces of truth—let me call them life codes—through which the abandoned person attempted to hold onto the real. As I listened, I was challenged to treat the accounts as evidence of the reality from which the abandoned had been barred and their failed attempts to reenter it. In this sense, these pieces ultimately gave language to the exclusion that was now embodied. Moreover, for the abandoned themselves, these accounts were spaces in which destinies were rethought and desires reframed.35

Consider the old black man standing barefoot against a wall and how he transformed social dying into speech. As I passed by, again and again he called me senhor (master) and, with downcast eyes, begged: “Senhor, can you, please, loan me your wife so that I can take her with me to see God, who has descended there in Porto Alegre?” I knew that he had seen me with Adriana, but I did not have a clue as to what he meant.

One day, I asked him about this epiphany.

“God is near the bus station,” the old man replied.

How do you know?

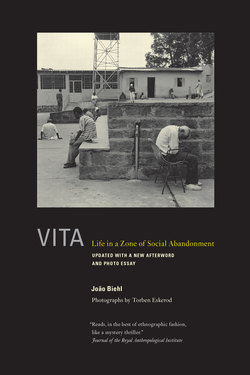

Osmar, Vita 2001

“I don’t know. People tell me. I also heard it on the radio. I have heard it for some time. Yes, senhor, I just want to go there and see God—and if you were to loan me your wife, I could go and see God.”

Why do you want to see God?

“It’s good to see God, to see and to get to know God.”

After a silence, I asked where he had come from.

“I am here now.”

How long have you been here?

“My family does not want me to see God, who has descended there at the bus station.”

Did your family leave you here?

“My family does not want me to see God. They say that I am not worthy of anyone. That I am worth nothing, that I am a very bad nigger. Truly, that’s what they say.”

Why did they leave you here?

“I don’t know; I didn’t wrong anyone.”

What did you do before getting to Vita?

“I always worked in a plantation . . . to sell for the market.”

How old are you?

“I don’t know. I have no birth certificate.”

He did recall his name: “Osmar de Moura Miranda.” Osmar said that he had always been a single man, that since he was a child he had known “nothing” of his parents. Later, a volunteer told me that Negão—“Big Nigger,” that is what they call him in Vita—had actually been brought there by “his boss.”

Now Osmar is a useless servant, so to speak; his family is that which never existed; and God (as I interpret it) is the dignity and liberty he never knew as a man of African descent in Brazil. “They brought me here where there is no work to do, and they never let me free. . . . Senhor, could you arrange things for me to leave?”

I explained that I could not, but I asked him where he would go if he left.

“To the streets, for I don’t have a place to live.”

Why is living in the streets better than here?

“In the streets, there is nobody to order me around.”

The accounts of Catarina, Osmar, and their neighbors represent agency. As these bits and pieces give language to a lived ex-humanness, they also work as the resources and means through which the abandoned articulate their experience. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the adjective “ex” means “former, outdated”; the preposition “ex” is used to mean “out of” in reference to goods; and the noun “ex” refers to “one who formerly occupied the position or office denoted by the context,” such as a former husband or wife. “Ex” also means “to cross out, to delete with an x,” and stands for the unknown.

I spent the months of August and December of 2000 working with Catarina in Vita. We talked for hours and hours, and I continued interviewing her neighbors and caretakers. During and between these visits, Catarina finished two more volumes of the dictionary, and I was increasingly amazed by her capacity to give form to her interior life, despite the crumbling of all hope. “I desire to be present”—that is what I heard her saying, time and again.

How to methodologically address her agonistic struggle over belonging? In the simplest of terms, for me it meant first to halt diagnosis, to find time to listen, to let Catarina take her story back and forth, to take her voice as evidence of a relatedness to a now-vanished lifeworld, and, throughout, to respect and to trust.