Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSociety of Bodies

I returned to Vita a week later, this time alone. With neighborly care, Catarina immediately asked, “Where is Adriana?” She remarked that she had enjoyed talking to both of us the other day. I sensed in her words an integrity that neither forgot bonds nor envied the bonds of others, the character of a time when one earned respect, if not from governmental institutions and employers, then at least from family members and neighbors. As simplistic as it may sound, this sociality was a life-giving force.

The left side of Catarina’s face was bruised. “I fell from the chair when I tried to reach the bathroom.” A volunteer overheard and contradicted her, claiming that she had thrown herself to the ground in a fit of rage.

Why aren’t you writing today?

“I already filled the dictionary.”

I asked if I could take another look at it. Catarina called India, a silent, twenty-something woman of Indian descent who was sitting on a bench nearby, and asked her to fetch the notebook, which was wrapped in a plastic bag inside a suitcase under her bed. She assured India: “It’s not locked.” As the story goes, India is “mentally retarded.” Her brother, they say, is a Pentecostal pastor who speaks about her on a radio program but never comes to see her.

I asked Catarina if she wanted to keep writing. When she responded, “Yes,” I ripped out several pages of scribbled field notes from my own notebook and gave the empty book to her. “Write your name and address here,” she asked.

“I want to leave, I want to leave,” a young black man named Marcelo broke into the conversation. Like the majority of those in Vita, his true name and origins were either unknown or did not matter. He kept looking straight into my eyes, his hands grasping a small suitcase: “Take me, take me with you.”

Many abandonados, like crippled Iraci, have no formal identification but recall a home, a family, a childhood, or simply freedom in the streets. “I also want to leave,” he told me. “I came from Lages, state of Santa Catarina. I was raised in the interior and like it better than the city. I lost my father and my mother. We had cows and pigs and planted corn and beans. I have ten siblings, all scattered. My sister put me on a bus to Porto Alegre. Nobody wanted to take care of me. I was already paralyzed. I got paralyzed when I was one-and-a-half years old. I lived in the streets for five years. Now I am forty-one years old and have been here for more than five years. Better to live in the streets than in a place like this for the rest of life.”

Vita “makes me nervous.” Iraci said. “Here one dies.” He has seen too many pass away. “During winter, it is pretty bad. I lost count of how many died this past year. It’s serious. This place is a sadness. I want to get out of here. This is not life. It’s the end of life. The one who is ill gets even more ill, and one gets nervous. I am a nervous man.”

What happens to the dead?

“When someone dies, the administration calls the morgue. They pick up the body and put it in the machine.”

What do you mean?

“They throw oil over the body and set the body on fire. Then it becomes ashes, and the ashes are thrown into the Guaíba River. If one is buried, it is only for a few days, for they need the grave for other people. That’s what I heard.”

During the long days in Vita in which nothing happens, Iraci and his friends, including India, whom he says he is dating, “keep track of time. . . . We tell each other which day of the month and which year it is, the year that passed and the year that will begin. One reminds the other. Today is December 30, 1999; tomorrow is December 31, 1999, right? See how smart I am? Thank God, my head works very well. I am not ill.”

I asked Iraci what was inside the plastic bag over his lap.

“The words of God.”

So you know how to read?

“No, but I understand them.”

What do the words of God say?

“They say, ‘The Lord is my shepherd, and I will lack nothing.’”

What else do you carry in here?

“Bread. I keep the crumbs I find so that I can eat during the day. Sir, I enjoyed talking to you very much. Do you have a pen?”

Yes.

“So, I want you to write my name in your book. It’s Iraci Pereira de Moraes. My name comes from my deceased mother. Her name was Dormíria Pereira de Moraes. The name of my deceased father was Laudino Pereira de Oliveira.”

Why didn’t you get your father’s name?

“I don’t know why. I was pushed to the side of the deceased mother. I think it’s good like this.”

Were you registered at birth?

“Yes, but I lost my documents in the streets. I must do them all over again.”

Iraci then again summed up his fate: “I tell you the truth, I have no father or mother. I have ten siblings. We were eleven; one died. We are scattered in the world. So I wanted to see if I could return to the interior. I have an acquaintance, a good friend of the family. He lives near the town of Arvelino Carvão.”

Catarina was listening. We resumed our conversation. Why, I asked her, do you think families, neighbors, and hospitals send people to Vita?

“They say that it is better to place us here so that we don’t have to be left alone at home, in solitude . . . that there are more people like us here. And all of us together, we form a society, a society of bodies.” And she added: “Maybe my family still remembers me, but they don’t miss me.”

Catarina had condensed the social reasoning of which she was the human leftover. I wondered about her chronology and about how she had been cut off from family life and placed in Vita. How had she become the object of a logic and sociality in which people were no longer worthy of affection, though they were remembered? And how was I to make sense of these intimate dynamics if not by trusting her and working through her language and experience?

India could not find the dictionary, so she brought the whole suitcase. A strong smell of urine, moisture, and also a kind of sweetness wafted out as I opened it. The contents of the suitcase were all that Catarina had in life: a few pieces of old clothing, some carefully assembled candy wrappers, fake jewelry, a bottle of cheap powder, a toothbrush, and a comb as well as several plastic bags containing magazines, books, and notebooks. “My worker’s identity card was kept by the hospital,” she noted.

I picked up the dictionary and read aloud some of her free-associative inscriptions.

Documents, reality

Tiresomeness, truth, saliva

Voracious, consumer, saving, economics

Catarina, spirit, pills

Marriage, cancer, Catholic church

Separation of bodies, division of the estate

The couple’s children

The words indexed the ground of Catarina’s existence; her body had been separated from those exchanges and made part of a new society.

What do you mean by the “separation of bodies”?

“My ex-husband kept the children.”

When did you separate?

“Many years ago.”

What happened?

“He had another woman.”

She shifted back to her pain: “I have these spasms, and my legs feel so heavy.”

When did you begin feeling this?

“After I had Alessandra, my second child, I already had difficulty walking. . . . My ex-husband sent me to the psychiatric hospital. They gave me so many injections. I don’t want to go back to his house. He rules the city of Novo Hamburgo.”

Did the doctors ever tell you what you had?

“No, they said nothing.”

Denial or resistance to the verdict “psychotic,” I thought. But what was the heaviness in her body that she repeatedly described? Just as they had the first time we met, in March 1997, Catarina’s words suggested that something physiological had preceded or was related to her exclusion as mentally ill, and that her condition worsened in medical exchanges. “I am allergic to doctors. Doctors want to be knowledgeable, but they don’t know what suffering is. They only medicate.”

Oscar, the infirmary’s coordinator, stopped by. Every time the good man saw me, he called me “O vivente”—“O living creature”—an expression I found eerie in that context. As we moved aside, Oscar explained that, as far as he knew, a hospital had sent Catarina to Vita because her family did not want to care for her. But he had no specific information to back this up.

“She is very depressed. Like the others, she feels rejected and imprisoned here. They are placed here, and nobody visits them.” He linked Catarina’s paralysis to a complicated labor, “a woman’s problem. She lost the child, it seems. We don’t know which hospital it happened in; we have no reports. These are things people say, but nobody truly knows. The fact is that people make pacts to get rid of the person, and that’s why we have institutions like Vita. That’s how things work these days.”

Oscar emphasized that probably 80 of the 110 people now in the infirmary (the population had significantly decreased since the time of Zé das Drogas’s administration) were “psychiatric cases.” But he agreed that Catarina was “a lucid person.” A person that no one listens to any longer, I added.

“When my thoughts agreed with my ex-husband and his family, everything was fine,” Catarina recalled, as we resumed the conversation. “But when I disagreed with them, I was mad. It was like a side of me had to be forgotten. The side of wisdom. They wouldn’t dialogue, and the science of the illness was forgotten. My legs weren’t working well. The doctors prescribe and prescribe. They don’t touch you there where it hurts. . . . My sister-in-law went to the health post to get the medication for me.”

According to Catarina, her physiological deterioration and expulsion from reality had been mediated by a shift in the meaning of words, in the light of novel family dynamics, economic pressures, and her own pharmaceutical treatment. Her affections seemed intimately connected to new domestic arrangements. “My brothers brought me here. For some time, I lived with my brothers . . . but I didn’t want to take medication when I was there. I asked: why is it only me who has to be medicated? My brothers want to see production, progress. They said that I would feel better in the midst of other people like me.”

But Catarina resisted this closure, and, in ways that I could not fully grasp at first, she voiced an intricate ontology in which inner and outer state were laced together, along with the wish to untie it all: “Science is our consciousness, heavy at times, burdened by a knot that you cannot untie. If we don’t study it, the illness in the body worsens. . . . Science . . . If you have a guilty conscience, you will not be able to discern things.”

Catarina said that she wrote in order “to know afterward,” as if she could not have been present in the circumstances that determined the course of her existence. Her spoken accounts and her writing contain the confused sense of something strange happening in the body—“cerebral spasm, corporal spasm, emotional spasm, scared heart.” Along with all those people coming in and out of her house, and her moving from house to hospital to other houses, it seemed there was a danger of becoming too many, strange to herself. “One needs to preserve oneself. I also know that pleasure in one’s life is very important, the body of the Other. I think that people fear their bodies.”

Writing helped her to endure the days in Vita, Catarina added. “Now and then, we also talk to each other. But the toughest are the nights, for then we are all alone, and one desire pushes the other. I have desire, I have desire.”

When I approached Iraci to say good-bye, he repeated that he and India were dating. “We take care of each other. Last night, I dreamed it was our wedding, and we were eating the cake. Then I woke up . . . and I was so hungry.” But the story is much more complicated. I learned that volunteers sometimes actually tied India to her bed to prevent her from masturbating in public. I also heard rumors that volunteers from the recovery area whose task it was to bathe the women had forced themselves sexually on India.

As I bade Catarina farewell, I asked to borrow the dictionary, for I wanted to study it. She consented. I told her that I would bring it back in August, and we would continue the conversation. She smiled and said that she had run out of ink. “I need another pen.”

I read the word she was trying to finish writing: CONTACT.

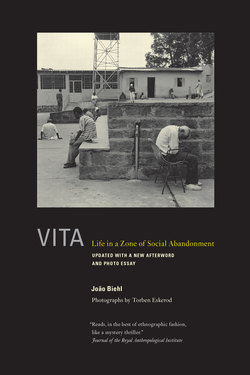

Iraci and India, Vita 2001