Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеA Zone of Social Abandonment

Vita sat on a hill of absolute misery. Gerson Winkler, a human rights activist, took me there in March 1995, along with Danish photographer Torben Eskerod. We were greeted by Zé das Drogas, Vita’s founder. “Vita is a work of love,” he told us. “Nobody wants these people, but it is our mission to care.”

The place was overcrowded and covered with tents. The few permanent buildings included a wooden chapel and a makeshift kitchen with no hot water. Some two hundred men lived in the recovery area, and two hundred additional people stayed in the infirmary. Each of these areas contained only one bathroom facility. The infirmary was separated from the recovery area by a gate, which was policed by volunteers, who made sure that those who were the most physically or mentally disabled would not move freely around the compound. These individuals wandered around in their dusty lots, rolled on the ground, crouched over or under their beds—when there were beds.

Each one was alone; most were silent. There was a stillness, a kind of relinquishment that comes with waiting, waiting for the nothingness, a nothingness that is stronger than death. Here, I thought, the only possible abstraction is to close one’s eyes. But even this does not create a distance, for one is invaded by the ceaseless smell of dying matter for which there is no language.

Like the woman the size of a child, completely curled up in a cradle and blind. Once she began to age and could no longer work for the family—“and worse,” explained Vanderlei, the volunteer who guided our visit, “she was still eating the family’s food”—relatives hid her in a dark basement for years, barely keeping her alive. “Now she is my baby,” said Angela, a former intravenous drug user, who most likely had AIDS. Angela had long ago lost custody of her two children and now spent her days caring for the old woman. “I found God in Vita. When I first came here, I wanted to kill myself. Now I feel useful. To this day, I have not discovered the grandma’s name. She screams things I don’t understand.” Yes, it was all horrific. Yet there seemed to be something ordinary and familiar in the ways these lives had been ruined. How to retrieve this history? And how to account for the unexpected relations and care emerging here? What is their potential, and how is it exhausted time and again?

A little later, words of salvation were everywhere. Loud, they emanated from the chapel that was now overcrowded with men undergoing rehabilitation, their heads bent as they quietly listened to several pastors of the Assembly of God. “You are fighting against God, but His words will give you victory over the world and the temptations of the flesh.” Improvised loudspeakers amplified these words of God and saturated the environment. In order to receive food, the men had to attend such sermons each day; they also had to give testimonies of conversion and memorize and recite Bible verses.

Seu Bruno spoke from the pulpit: “Brothers, faith in God will make you win over the world. I came here in bad shape. I did the worst things in the world. At sixteen, I left home, and I tried to be free. I was involved with alcohol and drugs. I was destroying myself. I am forty-eight years old. I lost my family. My three children want nothing to do with me. When I began to beg, my friends also left me. Vita was the only door open to me, and here the word of God opened my mind . . . and I began to see that I have value.”

Many of the men who had already passed through the recovery area took over a nearby spot of land, where they built shacks. A slum, known as the village (vila), formed on the outskirts, as if Vita were radiating outward. The economy of the streets persisted there. Although Vita was presented as a rehabilitation center, drugs moved freely between the facility and the village. I was told that criminals used the village as a hideout from the police. And there was a consensus among city officials and medical professionals that nobody actually recovered at Vita. How could they? Vita means life in a dead language. There were rumors that Zé das Drogas and his immediate assistants were embezzling donations, and even talk of a clandestine cemetery in the woods.

For Zé, Vita, despite all its disarray, was “a necessary thing. . . . Someone has to do something.” State and medical institutions as well as families were complicit in its existence, and they continued bringing bodies of all ages to die in Vita. Zé’s rhetoric was filled with outrage. He quoted the Old Testament and made a case for himself as a prophet: “While we are struggling, others are sleeping and not doing anything. One sees so much injustice that there are no words to express it.”

Stories about the tragedies of Vita were heard in millions of households. Much of the charity that kept Vita functioning was channeled through the work of Jandir Luchesi, a state representative and a famous radio talk-show host. With more than twenty local affiliated stations, his “Rádio Rio Grande” reached nearly 50 percent of the province’s population (some nine million people). During his morning show, Luchesi often put abandonados on the air, pleading with and scolding his radio audience: “Does anyone know this person? Who on earth could have done this to him?” Voicing moral indignation over the fate of the abandoned, Luchesi attracted donations of food and clothing while also carrying out his own political campaigns. Yet in spite of this impressive publicity, Vita was visited mostly by crentes (believers), poor volunteers from nearby Pentecostal churches who brought donations and tried to convert the abandoned. There were also sporadic visits by a few health professionals, such as Dr. Eriberto, who spent two hours a week administering donated medications and writing medical reports.

Only a few of the abandoned looked at us as we entered the infirmary. As they moved around or were moved, their bodies seemed passive, most likely an effect of drugs. Still, we thought, they must plan to leave this place. But we were told that when some manage to escape, they return, humiliated, begging to be allowed back. There is no other place for them to go. Who will hear their stories on the radio and “recognize that that is me”?

A middle-aged man was screaming, “Sou capado!” (I am castrated). As we approached, he stretched out his left arm and pretended to inject himself. “Who knows what has happened to him?” a volunteer shrugged. The man kept screaming, “Sou capado, sou capado!” They belong to Vita: simple people who still recollect being fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, uncles, aunts, grandparents—unclaimed lives in terminal desolation. If anthropologist Robert Hertz is right in arguing that the deceased is not only a biological entity but also a “social being grafted upon the physical individual” (1960:77), one wonders what kind of political, economic, medical, and social order could allow such a disposal of the Other, without indicting itself.

During the first day that Torben and I spent in Vita, we came upon a middle-aged woman sitting on the ground; she crouched over a stream of urine, her genitals matted with dust. As we approached, we could see that her head was full of small holes: worms burrowed in the wounds and under the scalp. “Millions of bichinhos [little animals], generated from her own flesh and dirt,” said Oscar, a former drug user, now being trained by Zé to become one of the infirmary’s coordinators. “We tried to clean it.” Torben could not bear to look. Momentarily paralyzed, he kept saying, “It is too much, it is too much.” The reality of Vita had overwhelmed picture-taking, too. This was a socially authorized dying, ordinary and unaccounted for, in which we participated by our gazing, both foreign and native, in our learned indifference and sense of what was intolerable. Yet rather than remaining paralyzed by moral indignation, we felt compelled to address life in Vita and the realpolitik that makes it possible. Not to represent it would equally be a failure.

Marcel Mauss, in his essay “The Physical Effect on the Individual of the Idea of Death Suggested by the Collectivity,” shows that in many supposedly “lower” civilizations, a death that was social in origin, without obvious biological or medical causes, could ravage a person’s mind and body. Once removed from society, people were left to think that they were inexorably headed for death, and many died primarily for this reason. Mauss argues that these fates are uncommon or nonexistent in “our own civilization,” for they depend on institutions and beliefs such as witchcraft and taboos that “have disappeared from the ranks of our society” (1979:38). As we saw in Vita, however, there continues to be a place for death in the contemporary city, which, like Mauss’s “primitive” practices, functions by exclusion, nonrecognition, and abandonment. In the face of increasing economic and biomedical inequality and the breakdown of the family, human bodies are routinely separated from their normal political status and abandoned to the most extreme misfortune, death-in-life.19

Where had this woman come from? What had brought her to this condition?

The police found her on the streets and took her to a hospital that refused to clean her wounds, much less to take her in. So the police brought her to Vita. Before living in a downtown public square, she had had legal residence in the São Paulo Psychiatric Hospital, but she had been released as “cured”—in other words, overmedicated and no longer violent. And before that? No one knew. She had passed through the police, through the hospital, through psychiatric confinement and treatment, through the city’s central spaces—and in the end she was putrefying even before death. It is clear that dying such as hers is constituted in the interaction of state and medical institutions, the public, and the absent family. These institutions and their procedures are symbiotic with Vita: they make death’s job easier. I use the impersonal expression “death’s job” to point out that there is no direct agency or legal responsibility for the dying in Vita.

What happened to this nameless woman was far from an exception—it was part of a pattern. In a corner, hunched over a bed in the women’s room sat Cida, who seemed to be in her early twenties. Diagnosed with AIDS, she had been left at Vita by a social worker from the Conceição Hospital in early 1995. During her early days at Vita, the volunteers began calling her Sida, the Spanish word for AIDS. Later, I was told that they had replaced the “S” in her new name with a “C”—“like in Aparecida, so that people would stop mocking and discriminating against her.” I was surprised to learn that the volunteers believed that Cida and a young man were the only AIDS cases in Vita. Too many of the wasted bodies I saw also had skin lesions and symptoms of tuberculosis. Oscar told me that Cida came from a middle-class family, but that no one ever visited her. She spoke to no one, he said, and sometimes did not eat for three or four days. “We have to leave the food in a bowl in the corridor, and sometimes, when nobody is watching, she comes down from her bed and eats,” explained the volunteer, “like a kitty.”

Here, animal is not a metaphor. As Oscar argued: “Hospitals think that our patients are animals. Doctors see them as indigents and pretend that there is no cure. The other day, we had to rush old Valério to the emergency. They cut him open and left surgical materials in there. The materials became infected, and he died.” What makes these humans into animals not worthy of affection and care is their lack of money, added Luciano, another volunteer: “The hospital’s intervention is to throw the patient away. If they had sentiment, they would do more for them . . . so that there would not be such a waste of souls. Lack of love leaves these people abandoned. If you have money, then you have treatment; if not, you fall into Vita. O Vita da vida [the Vita of life].”

As I see it, Oscar and Luciano were not using the term “human” in the same way human rights discourses do, with a notion of shared corporeality or shared reason. Neither were they opposing it to “animal.” Rather than referring to the animal nature of humans, they spoke of an animal nature of the medical and social practices and of the values that, in their ascendancy over reason and ethics, shape how the abandoned are addressed by supposedly superior human forms. “There was no family; we ourselves buried old Valério. The human being alone is the saddest thing. It is worse than being an animal.” Although they emphasized the “animalization” of the people in Vita, Oscar and Luciano conveyed a latent understanding of the interdependence of the terms “human” and “animal” and of a hierarchy within the human itself. The negotiation over these boundaries, particularly in the medical realm, allows some human/animal forms to be considered inappropriate for living.20

In the face of the First World War, Sigmund Freud wrote an essay entitled “Thoughts for the Times on War and Death.” Freud spoke of a generalized wartime confusion and disillusionment that he also shared and of people being without a glimmer of the future being shaped. “We ourselves are at a loss as to the significance of the impressions which press in upon us, and as to the value of the judgments which we form . . . the world has grown strange to [us]” (1957b:275, 280). This sense of an ethical and political void experienced by “helpless” citizens had been provoked by “the low morality shown by states which pose as the guardians of moral standards” and by the brutality demonstrated by individuals who, “as participants in the highest human civilization, one would not have thought capable of such behavior” (280). At stake, in Freud’s account, was not the citizen’s failure to empathize with the suffering of fellow humans but his or her estrangement from imaginaries gone awry. This anxiety over the discredited imaginaries of the nation-state and of supposedly inexorable human progress stood for people’s actual incapacity to articulate the function of the Other’s death in the organization of reality and thought.

We moderns—this is how I read this melancholic Freud—operate with an instrumental idea of the human and are time and again faced with a void in what constitutes humanness. One’s worthiness to exist, one’s claim to life, and one’s relation to what counts as the reality of the world, all pass through what is considered to be human at any particular time. And this notion is itself subject to intense scientific, medical, and legal dispute as well as political and moral fabrication (Kleinman 1999; Povinelli 2002; Rabinow 2003; Asad 2003). It is in between the loss of an old working idea of humanness and the installment of a new one that the world is experienced as strange and vanishing to many in Vita. I do not refer here to the universal category of the human but rather to the malleability of this concept as it is locally constituted and reconstituted, with semantic boundaries that are very fuzzy. Above all, the concept of the human is used in this local world, and it cannot be artificially determined in advance in order to ground an abstract ethics.21

Vita is the word for a life that is socially dead, a destiny of death that is collective. “These people had a history,” insisted Zé. “If the hospitals kept them, they would be mad; in the streets, they would be beggars or zombies. Society lets them rot because they don’t give anything in return anymore. Here, they are persons.” Zé was right on many counts: disciplinary sites of confinement, including traditionally structured families and institutional psychiatry, are breaking apart; the social domain of the state is ever-shrinking; and society increasingly operates through market dynamics—that is, “you shall be a person there, where the market needs you” (Beck and Ziegler 1997:5; see also Lamont 2000).22 Yes, treating the abandonados as “animals” might release individuals and institutions from the obligation of supplying some sort of responsiveness or care. But I was also intrigued by the paradox voiced by Zé: that these creatures—apparently with no ancestors, no names, no goods of their own—actually acquired personhood in the place of their dying. The idea that personhood, according to Zé, can be equated with having a place to die publicly in abandonment exemplifies the machinery of social death in Brazil today—its workings are not restricted to controlling the poorest of the poor and to keeping them in obscurity. But the idea of “personhood in dying” also challenged me as an ethnographer to investigate the ways people inhabited this condition and struggled to transcend it.

Though no money circulates in Vita’s infirmary—there is nothing to be bought or sold—many inhabitants hold something: a plastic bag, an empty bottle, a piece of sugar cane, an old magazine, a doll, a broken radio, a thread, a blanket. Some nurse a wound or simply count their fingers. One man carries garbage bags with him day in and day out. They are his sole property. He bites people who try to take the trash away. “Sometimes there is food rotting in these bags, even feces,” said Luciano. “Then we give him a tranquilizer, put him to sleep, and replace the things in the bags.” The volunteer added, “Any institution needs control in order to exist,” without explaining where the prescriptions for the tranquilizers came from.

At first, I saw the objects carried by the abandoned as standing for their lack of relationship with the world outside Vita as well as for their past experiences, impossibly distant but remembered. In this sense, the objects are a defense against everything that banishes these people from the field of visibility and planning, everything that establishes them as already dead. As I kept returning to Vita, I also began to see the objects as forms of waiting, as inner worlds kept alive. Words, too, though powerless to alter conditions, are still a source of truth here. Both objects and disjointed words sustain the sense of a search in these people, their last attachment to the possibility of redis covering a tie or of doing something with what is left of their existence. This desire is something that one does not give up, though it might be taken away.

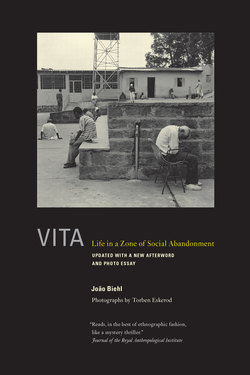

The photographs Torben Eskerod took during our first visit to Vita in 1995 and on a later visit in December 2001 give us a sense of the persons who were facing this kind of abjection.23 “Photographs are a means of making ‘real’ (or ‘more real’) matters that the privileged and the merely safe might prefer to ignore,” writes Susan Sontag (2003:7). It would be too much to say that Eskerod’s photographs make real the abandonment in Vita. They are at most an initial approximation, a sincere attempt to render visible this tragic experience. They are his personal testimony to the abandonment in their bodies and to a wakefulness that accompanies social death.

If these photos are shocking, it is because the photographer wants to focus on our learned indifference and provoke some ethical response. If they are haunting, it is because this is an enduring reality, not so far from us. We manage not to see the abandoned in our homes and neighborhoods, rich and poor. How are our self-perceptions and our priorities for action dependent on this blindness?

Arthur and Joan Kleinman argue that the globalization of images of suffering commodify, thin out, and distort experience. This process corroborates our epoch’s dominating sense that “complex problems can be neither understood nor fixed,” fostering further “moral fatigue, exhaustion of empathy, and political despair” (1997:2, 9; see also Boltanski 1999). The key verbs here are “to understand” and “to hope”—so that people’s destinies might be different. For the Kleinmans, the challenge is to ethnographically chart how large-scale forces relate to local history and biography, and thereby to restore context and meaning to the lived experience of suffering captured by the artist.

How to bring into view the reality that ruins the person?

Signaling a shift from the artistic to the political function of artwork, Walter Benjamin (1979) suggested that captioning would become the most important part of photography, the foundation of meaning.24 For some time after our first visit to Vita, I thought that these photos were enough, that they did the work of bringing this reality out of concealment and into the public eye. The photos stayed with me and fueled a desire to return to Vita—not to find a caption but to try to further engage some of the abandoned, to listen to and record what they thought of their plight, who they once had been. By hearing them and tracing their trajectories, I hoped to prevent them from remaining merely depictions of powerlessness and to address the routine domestic and public interactions that foreclosed the possibilities of their lives. Ethnography helps to disentangle these knots of complexity, bringing into view the concrete conditions and spaces through which human existences become intractable realities. And yet, as I began to know these people better, I was challenged to think of life in Vita also in terms of anticipation and possibility.

Before we went back to Vita in December 2001 to conclude the photographic work, I briefed Torben on what my research had found in Vita and beyond. Learning about Catarina’s life history and having clues to the lives of some of the other abandoned affected his approach to the photography. In his earlier pictures of life in Vita, he mostly photographed fragments of people’s bodies, conveying their death-in-life and overall detachment from a larger social body. This time, with some of their fragmented histories in mind, Torben pictured the abandoned at a certain distance, I would say. Enclosure, adjacency to others, and introspection are shown. Older than their bodies tell and yet with time left, the people of Vita appear more familiar to us than before, left with their own intimacy and a way to fold into themselves and reflect.

Infirmary, Vita 2001

Pedro, Vita 1995