Читать книгу Vita - João Biehl - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

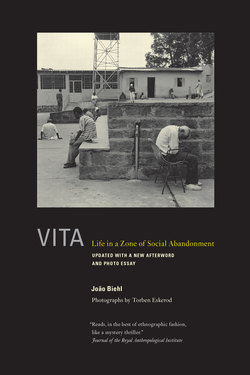

ОглавлениеThe House and the Animal

“Even if it is a tragedy? A tragedy generated in life?”

Those were Catarina’s words when I asked her for the details of her story the next day.

“I remember it all. My ex-husband and I lived together, and we had the children. We lived as a man and a woman. Everything was as it should be; we got along with the neighbors. I worked in the shoe factory, but he said that I didn’t need to work. He worked in the city hall. He used to drink a bit after work when he played billiards in a bar. I had nothing against that.

“One day, however, we had a silly fight because he thought that I should be complaining about his habits and I wasn’t. That fight led to nothing. Afterward, he picked another topic to fight about. Finally, one day he said that he had gotten another woman and moved in with her. Her name was Rosa.

“What could I do? Anderson said, ‘Mom, father has another woman. Aren’t you going to do something about it?’ What could I do? ‘Alessandra and I must have a destiny,’ he said. ‘If this woman wants my father, he should stay there, because it is impossible for a man to have two homes, two families. . . . He is making a cancer here.’ I kept wondering what to do. . . . He wanted to divide himself between both of us.”

I remembered the phrase “the separation of bodies” in Catarina’s dictionary, and it seemed to me that her pathology resided in that split and in the struggles to reestablish other social ties.36 In Vita, out of that lived fragmentation, the family was remembered. Her associations continued on the theme of the changing family, which was the cause of much pain and confusion.

“My mother was living with us. I had to take care of my mother. She couldn’t walk anymore; she had rheumatism and wanted treatment. I also have rheumatism. My father had had another family since we were kids; he stayed in the countryside. My father also wanted to heal, for he got poisoned planting tobacco. My ex-husband wanted to do the same as my father did, but I said ‘no’ to that kind of arrangement. So the marriage ended. During my last pregnancy, he left me alone in the hospital. He didn’t go there to see if the baby had been born or not. I had to be mother and father at the same time.”

According to Catarina, her husband repeated what her father had done. In marriage, she found herself once more in a fatherless family. Her father had been poisoned; he worked for a big company and for another family. Her mother lived with the young couple. The disease that paralyzed her was also emerging in Catarina’s body. When it was time for her to give birth to her last child, Catarina was left alone in the hospital, to be both mother and father to an unwanted child. All these references resonated with a fragment in the dictionary in which a breathless child was said to suffocate the mother:

Premature

Born out of the schedule

Out of time, out of reason

Time has passed

The baby’s color changes

It is breathless

And suffocates

The mother of the baby

Nothing could account for what was happening. “Out of time, out of reason,” she was feeling untimely. As our conversation continued, Catarina again emphasized her agonistic effort to adhere to what was “normal” and behave the way a woman was supposed to in that world. She alluded to the occlusion of her thinking as if it were daydreaming and to an urge to leave the home in which she was locked. The house and the hospital doubled as each other, and she was left childless:

“I behaved like a woman. Since I was a housewife, I did all my duties, like any other woman. I cooked, and I did the laundry. My ex-husband and his family got suspicious of me because sometimes I left the house to attend to other callings. They were not in agreement with what I thought. My ex-husband thought that I had a nightmare in my head. He wanted to take that out of me, to make me a normal person. They wanted to lock me in the hospital. I escaped so as not to go to the hospital. I hid myself; I went far. But the police and my ex-husband found me. They took my children.”

When was the first time you left home?

“It was in Novo Hamburgo. In Caiçara, I didn’t leave the home; it was in the countryside. One always has the desire to leave. I was young then. But pregnant and with a child, I wouldn’t leave. . . . When we first got to Novo Hamburgo, we rented a place at Polaco’s. I left home and ran because . . . who knows? Because . . . he was late in coming home from work. . . . And one day he left work earlier and rode the motorcycle with girls. I went to the bar and asked for a drink. I was pretty courageous and left. I was kind of suffocating inside the house. Sometimes he locked us in, my son and I, and went to work. I kept thinking, ‘How long will I remain locked?’ I felt suffocated. I also felt my legs burning, a pain, a pain in the knees, and under the feet.”

Did he find another woman because you left home? Or why did it happen?

“No.”

After a silence, Catarina answered a question I had not asked: “He didn’t leave me because of my illness either. . . . That didn’t bother him.” Yet it struck me that her statement affirmed the very thing she sought to deny: the key role played by her physiology within the household, of which she was both conscious and unconscious. She then added that jealousy was her husband’s basic state of consciousness.

“He was jealous of me. He used to say how ugly I was. He wanted me to stay in the wheelchair . . . so that he could do everything as he wished. He found another woman because he wanted to be a true macho. One day, he came back and said, ‘I don’t want you anymore.’ I said, ‘Better for me. I want a divorce.’ We separated from bed, bath, table, home, and city. I wanted a divorce. Divorce is mine, I asked for it first.”

This man’s virility was dependent on negating and replacing her. And the doctors, according to Catarina, helped to objectify the new family arrangement, making it impossible to truly reflect about what was going on.

“The doctors listened only to him. I think that this is wrong. They have to listen to the patient. They gave me pills. A doctor shouldn’t have contempt for the patient, because he is being unjust. He only writes prescriptions and doesn’t look at the person. The patient is then on a path without an exit. At home, people began to call me ‘mad woman’—‘Hey, mad woman, come here,’ that’s what they used to say.”

The psychiatric aura of reality.

You seem to be suggesting that your family, the doctors, and the medications played an active role in making you “mad,” I said.

“Instead of taking a step forward, my ex-husband took life backward. The doctors he took me to were all on his side. I will never live in Novo Hamburgo again. That’s his land; he rules that territory. Here in Vita, at least I can transmit something to people, that they are somebody. I try to treat everybody with simplicity. He first placed me in the Caridade Hospital, then in the São Paulo—seven times in all. When I returned home, he was amazed that I recalled what a plate was. He thought that I would be unconscious of plates, pans, and things and conscious only of medication. But I knew how to use the objects.”

This is how I was interpreting Catarina’s account: her condition was the outcome of a new family complex that was given agency within everyday economic pressures, governing medical and pharmaceutical practices, and the country’s discriminatory laws. These technical procedures and moral actions took hold of her: she experienced them as a machine with no exit in which mental life was taken backward.37

Through her increasing disability, all of the social roles Catarina had forcefully learned to play—daughter, sister, wife, mother, migrant, worker, patient—were being annulled, along with the precarious stability they had afforded her. To some degree, these cultural practices remained with her as the values that motivated her memory and her sharp critique of the marriage and extended family who had amputated her as if she had only a pharmaceutical consciousness. Yet this network of relatedness, betrayals, and institutional arrangements seemed to have affected Catarina profoundly, leaving her able to symbolize her condition only through the dilemmas and certainties of the world of infancy. As she put it: “When I was a child, I used to tell my brothers that I had a piece of strength that I kept to myself, only to myself.”

Catarina continued: “My ex-husband’s family got mad at me. I have a conscience, and theirs is a burden.” Interestingly, as she reconstructed the actions of her ex-family, she described something that, speaking as an amputated being, she could not perceive as a plot against her.

“One day, Nina—she is my ex-husband’s sister—and Delvani, her husband, came to my house, and I began to tell them what I thought. He said, ‘Catarina, we have put our shack for sale. If you want, we can simply trade places, and you can get out of here.’”

The goods that had been left to Catarina after the separation from her husband were now taken as well by these relatives. In this transaction, disguised as a fair exchange, the misery of one became good business for the other. Catarina quoted the brother-in-law, who pretended not to know the business aspect of the trade: “‘This idea just came to mind now; Nina and I have not discussed this before,’ he said. So they kept my house, and I moved into theirs. I recall when I took the little girl and we went into the moving truck. I had such a pain in my legs, such a pain. . . . My legs felt so heavy. I was nervous.”

What happened in the new house?

“I went to live alone. Anderson and Alessandra stayed with their grandmother. She took care of them; she could walk. At first, Ana was with me, but then Tamara kept her for longer and longer. She liked to prepare her birthday party. They are well-off people. She took my little daughter, adorned her, and took photographs. And I stayed in the house.”

And next? I kept pushing the recollection.

“My shack burned down. The fire began in my neighbor’s shack—her TV set exploded. There was a short-circuit, and it was all on fire. Divorce is fire. It all burned down. I stayed a few weeks with my brothers. A week in the house of one and a week in the house of the other. Ademar looked at me and said, ‘We progressed on our own . . . and now this woman lying here.’ My brother wants to see production, he wants one to produce. . . . He then said, ‘I will sell you.’”

I had to stop her for a moment. I don’t understand, Catarina.

From that point, her account became more and more elliptical, oscillating between what I understood as a fantasy that equated production with the brothers’ demand that she procreate and the account of a pharmaceutically mediated form of fraternal cruelty. Catarina, however, insisted that the siblings respected her and that they were not ex-brothers: “They liked me and wanted me to stay in the house. They didn’t demonstrate it, but they wanted us to remain together.” This image of the brothers, I thought at the time, was what remained of the house of infancy. What happened in that space that was left? What in life made that space remain?

“I fell sick while I was in my other brother’s house. It was such a bad flu—it was a cold winter. They gave me such strong medication that I couldn’t do anything but sleep. Day and night were the same for me. My brother told me that I had to go. He said that he already had four children, that I only had three, that I was obligated to have five or six kids, like my mother. He didn’t realize that he demanded from me what he asked from himself. He married twice. The first woman died giving birth to a son. To do what? So he got another woman and now has three children with her.

“Like Altamir, he also has an auto repair shop. He always has money . . . but, here, I don’t have money. Here, we live from donations. The important thing is not to have money and things but one’s life. That is very important—life and to give opportunity to whoever wants to be born. . . . My brother used to say that we, my husband and I, had too few children, too little sexual relation.”

The demands for economic progress made by the brothers and the changing value of kinship ties became entangled in a battle over the discarding of Catarina’s body. In order to endure being left to die in Vita, Catarina has recomposed the ruined fraternal tie, I thought. Desire finds lost objects. Yet the men in Catarina’s account—the brothers, the ex-husband, and the brother-in-law—seemed beyond the tragic mode. Their actions were guided by other interests: getting rid of Catarina before she became an invalid like her mother, taking her house, having another woman. In reality, Catarina could not be the human that these men wanted.

“After my ex-husband left me, he came back to the house and told me he needed me. He threw me onto the bed, saying, ‘I will eat you now.’ I told him that that was the last time. . . . I did not feel pleasure, though. I only felt desire. Desire to be talked to, to be gently talked to.”

In abandonment, Catarina recalled sex. There was no love, simply a male body enjoying itself. No more social links, no more speaking beings. Out of the world of the living, her desire was for language, the desire to be talked to. I reminded Catarina that she had once told me that the worst part of Vita was the nighttime, when she was left alone with her desire.

She kept silent for a while and then made it clear that seduction was not at stake in our conversation:

“I am not asking a finger from you.”

She was not asking me for sex, she meant.

Catarina looked exhausted, though she claimed not to be tired. At any rate, it seemed that she had brought the conversation to a fecund point, and I also felt that I could no longer listen. No countertransference, no sexual attraction, I thought, but enough of all these things. The anthropologist is not immune. I promised to return the next day to continue and suggested that she begin to write again.

But my resistance did not deter her from recalling her earliest memory, and I marveled at the power of what I heard—an image that in its simplicity appeared to concentrate the entire psyche.

“I remember something that happened when I was three years old. I was at home with my brother Altamir. We were very poor. We were living in a little house on the plantation. Then a big animal came into the house—it was a black lion. The animal rubbed itself against my body. I ran and hugged my brother. Mother had gone to get water from the well. That’s when I became afraid. Fear of the animal. When mother came back, I told her what had happened. But she said that there was no fear, that there was no animal. Mother said nothing.”

This could have been incest, sexual abuse, a first psychotic episode, the memory of maternal and paternal abandonment, or a simple play of shadows and imagination—we will never know.

The image of the house, wrote Gaston Bachelard, “would appear to have become the topography of our intimate being. A house constitutes a body of images that give mankind proofs or illusions of stability” (1994:xxxvi).

In this earliest of Catarina’s recollections, nothing is protecting the I. It is in Vita that she recalled the animal so close to the I. This story speaks to her abandonment as an animal as well as to the work the animal performs in human life. In this last sense, the animal is not a negation of the human, I thought—it is a form of life through which Catarina learned to produce affect and which marks her singularity.

When I told her it was time for me to leave, Catarina replied, “You are the one who marks time.”