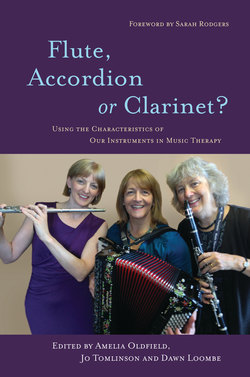

Читать книгу Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? - Jo Tomlinson - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

The Clarinet

Contributors: Henry Dunn, Amelia Oldfield (introduction

and case vignette), Catrin Piears-Banton and Colette Salkeld

Introduction

Compared with other orchestral instruments, the clarinet is a relative newcomer. It was invented near the beginning of the 18th century and appeared increasingly often in orchestras throughout that century. As a result clarinettists do not have original parts to play in earlier music, although there are many successful transcriptions or arrangements where clarinets might play viola, oboe, French horn, trumpet and sometimes even violin or flute parts if these are not too high. The range of the modern B clarinet is from D below middle C, to G two-and-a-half octaves above middle C (or higher depending on the player). It can sound smooth and mellow in the lower range, and more clear and piercing higher up. Composers who have written for the clarinet include Mozart, Brahms, Poulenc, Gershwin, Copland and Finzi. In addition to concertos and orchestral parts, the clarinet features in a wide range of chamber music, as well in wind band music, and clarinet choirs, which include bass and contrabass clarinets, alto clarinets and small high-pitched E clarinets. The instrument is also prominent in jazz, folk music and traditional Klezmer music.

The clarinet has a mouthpiece with a single reed, which has to be moist for the instrument to play effectively. When using the clarinet in music therapy, this can be a disadvantage if the music therapist wants to pick up the instrument to respond quickly to a client, as the reed might have dried out. It is possible to use plastic reeds to overcome this problem, but this changes the quality of the sound.

Most clarinet playing music therapists use mainly B instruments in their clinical work, although occasionally bass clarinets make an appearance because of their particularly appealing sound in the lower register. Henry Dunn mentions his interest in jazz improvisation in his contribution.

The clarinet is a transposing instrument where, for example, on the B instrument a written C sounds a tone lower: B. In addition, unlike the flute or the oboe, the fingering is different in each octave. To deal with these problems orchestral and chamber music clarinet parts are often written for both B and A clarinets, and most classical players will have a pair of instruments and can quickly swap from one to the other. However, since most music therapists only bring B clarinets to sessions, when improvising they have to get used to transposing as well as overcoming the technical difficulties of using different fingerings in different octaves. It is also possible to get clarinets in C, but these are comparatively rare.

Figure 1.1 Clarinet range (B, A and E)

The clarinet is a popular instrument and is played by many music therapists, so it has not been difficult to find contributors for this chapter. Both Salkeld (2008) and Oldfield (2006a and 2006b) have written before about how they have used the clarinet in their clinical music therapy practice. Salkeld matches her client’s energetic and loud music on the buffalo drum by playing a bright melody in C major on the clarinet and marching around the room with him. After this he appeared more confident, not needing to hide any more (Salkeld 2008, p.151). Oldfield writes about many different uses of the clarinet when working with children and families at a child development centre (Oldfield 2006a) and when working in child and family psychiatry (Oldfield 2006b). She lists a number of reasons why she feels the clarinet is invaluable in her work (Oldfield 2006a, pp.34–35), and many of these overlap with the ‘Clarinet characteristics in music therapy practice’ described at the end of this chapter. When describing her improvisation on the clarinet during music therapy sessions she writes:

On the clarinet, I often play in A minor, which in reality is G minor as the clarinet is a transposing instrument in B. This is because the reed horns that I have are pitched at G and C, and as I often offer these reed horns to children and parents while I am playing the clarinet, I have become accustomed to improvising in this key. Quite often, I might be moving around the room while I play, so my phrases might be quite long and flowing with no predictable rhythms to accommodate the child’s unpredictable movements. At other times I use quite jazzy styles and rhythms as the clarinet is well suited to this style. (Oldfield 2006a, p.33)

Forging connections with the clarinet

Catrin Piears-Banton

I was inspired to learn the clarinet after seeing Emma Johnson win Young Musician of the Year in 1984. I met her at a concert the following year when I had already started lessons, and we have been in touch ever since. Emma’s clarinet playing spoke volumes to me, she showed confidence and communicated such emotion in her playing; there was something about the sound of the rich tones of the clarinet that I wanted to experience. As a shy and tentative young girl, Emma’s gentle demeanour and quietly spoken words of support gave me, as a shy and tentative young girl, hope that I too could express a world of difference in my clarinet playing.

As a music therapist, playing the clarinet in my clinical work gives me access to a variety of characteristic sounds across a wide pitch range: from the rounded, smooth resonance of the chalumeau register to the soaring, vibrant higher notes. This type of music can communicate humour, joy, drama, pain, sympathy, melancholia, as if I am truly speaking the emotion through my breath. My facial expression may stay similarly pursed as I play but the sounds produced can speak more than words and penetrate deeply within the shared musical experience.

Case vignette: Ben

Ben, a six-year-old child on the autistic spectrum, was referred to music therapy for help with his frustration at not being understood and to support him with difficulties in turn-taking and sharing.

Figure 1.2 Clarinet hide-and-seek

(photo by Dr. Alan Robson FRPS)

From our first few sessions, I noticed that Ben responded vocally when I played my clarinet. Ben was most comfortable using his voice and he would experiment with a range of different sounds, as if exploring his capacity for vocal expression. My use of the clarinet could acknowledge something of his vocalisations without being too imitative.

Ben sometimes came and touched the bell of the clarinet for a moment as I played, feeling the vibrations with his hand. At first, Ben would often move far away from me, sitting or standing with his back to me as he vocalised. It was my use of the clarinet that enabled us to play together and forge something of a connection. Ben’s vocal sounds were playful and rhythmic and he gained confidence in his own sounds when he hid behind some long curtains in the music therapy room.

Our vocal and clarinet interactions and exchanges evolved into a musical game of hide-and-seek with Ben hiding behind the curtains as I crept nearer and nearer to him, the sound of my clarinet giving him a clue as to how close I was getting. I also sometimes played the mouthpiece alone – a loud and vibrant sound that Ben found comical.

Being able to move around the room freely whilst playing the clarinet supported the development of this shared music-making and helped Ben to explore and tolerate shared interaction. Ben’s confidence in relating to and trusting others increased, and our hide-and-seek turn-taking game came out from behind the curtains as Ben gained a curiosity and confidence in exploring the other instruments in the room. Eventually Ben invited me to play the bongos with him, demonstrating something of how far things had come from the opposite sides of the room and behind the curtains.

Case vignette: Michael

I began working with Michael, 45, when he was referred to the adult community mental health service for support with his increasingly isolated lifestyle. Michael was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. Music therapy aimed to help Michael build confidence to feel safe with others and re-engage with the community.

Having taught himself the keyboard, Michael had spent the best part of several years playing for long hours at home on his own. Though committed to music therapy, Michael struggled to relate to me in our sessions: his instrument of choice was a large electronic keyboard set at full volume and mostly set to textured synthesised sounds. Michael was confident performing to me in his own particular musical style of busy patterns at varying tempos, and he played continuously with no obvious pulse; alternatively he would play songs that he had composed. Michael’s music was difficult to engage with, and he seemed to maintain a musical wall of defence around himself.

Most instruments I played to meet Michael in his music were rendered powerless and ineffective as he sped up and slowed down or stopped suddenly, only to then start a different sequence of chordal structures. I chose to introduce my clarinet in our sessions, and this was accepted by Michael, but a competitive dynamic arose. I knew I needed somehow to play in parallel to Michael’s music, to gain his interest and trust not by acknowledging his patterns – which seemed to feel like hijacking to Michael – but by being a non-threatening ‘other’. This was achieved by providing contrapuntal motifs at the ends of phrases as Michael performed his songs, or inserting a few trills, or long-held notes over his busy keyboard playing.

Gradually, over a few weeks, Michael seemed to expect me to play my clarinet in this way, and began to leave longer gaps between his phrases for me to play; he sometimes even imitated my clarinet motifs in his music. Over time the improvisations took on a symphonic, soundtrack feel to them; there was less anxiety and he was able to listen and accept my music as complementary to his own, rather than threatening. Michael was then able to acknowledge the shift in the music verbally and to relate some of his musical defences to his fear of society.

From the beginning, Michael had been dismissive of the percussion instruments in music therapy and it took my use of a sufficiently complex instrument in the form of the clarinet to make a connection with him. The challenge with Michael had been for him to hear and accept me. If I played the piano, it was heard as an attack on his skill and sound perhaps, and was probably too close emotionally in some way. The clarinet was my instrument; separate and distinct from Michael’s keyboard, yet as meaningful to me as his keyboard was to him. We could be two people conversing, but through our own chosen, personal instrument that we both had our own way of playing. Michael played patterns and songs dear to him, and I improvised around his structure. Eventually he could improvise, share and acknowledge something of the experience with me.

Case vignette: Group

I currently use my clarinet regularly in a group for people with severe to profound and multiple learning disabilities. The group’s music is often very much centred around people’s personal vocal and body sounds. I find that by blowing air through the clarinet, rather than sounding notes, I can acknowledge breathy sounds from all group members that so often become a very important part of sessions for this group. I can also offer something with a unique tone that has become my non-verbal voice in the group.

When I am assessing clients or when I sense an uncertain quality to the dynamic in the therapy room, I know that I can pick up my clarinet and explore the situation with confidence. Alongside the personal and emotional connection I have with playing the clarinet, I can rely on the tone of the instrument to match, acknowledge and support the client in their playing, particularly when they play chordal instruments – piano, keyboard, guitar even – in such a way that they become increasingly absorbed in their playing, filling the room with a dense texture of sound. Playing the clarinet can state my presence subtly or not so, depending on the need, and can challenge or tenderly coax a response as appropriate. I consider the clarinet an instrument for many eventualities that is a more flexible alternative to my voice, yet as personal, unique and communicative.

The clarinet in a family’s loss

Colette Salkeld

I have been playing the clarinet since the age of eight, and prior to training as a music therapist I worked as a professional clarinettist for a number of years. I have always felt the clarinet was an extension of myself, a means of personal expression, a way of conveying meaning beyond words. Since working as a music therapist I have found that the clarinet seems to allow me the freedom to respond empathically and to be physically closer to the clients, particularly in group work.

Case vignette: Artem

Artem was a five-year-old boy from Ukraine who was in the terminal phase of cancer. I was asked to see him during my first week in a new music therapy post and was told that he had only a matter of weeks to live. I was aware of the work of Nigel Hartley at St. Christopher’s Hospice and the importance of supporting the whole family at this stage in a child’s life, and because the work was in Artem’s room my intuitive response was to take my clarinet.

Session 1: Lullabies and dreams

When I first met Artem he was lying in his hospital bed, in a private room, with his father sitting beside him. Because of the nature of his cancer, Artem had lost the ability to use his limbs and also his voice. His only means of communication was his eyes. To say ‘yes’ he would look up, and to say ‘no’ he would look down. I was aware that I was coming in to this family’s life at a very sensitive time and I did not want to appear as an uninvited guest. Artem’s play specialist, who had worked with him for a number of months and had made the referral for music therapy, introduced me and stayed for the first session. In this way she provided the link, as someone whom they could trust.

To begin with, I sat beside Artem and sang hello to him, and following this Artem’s father supported him in strumming on the guitar. Artem communicated that he enjoyed this and during this time I improvised vocally, to support his playing. The play specialist then said that Artem had wanted to become a soldier and loved marching music. It was at this point that I used my clarinet for the first time and, supported by his father, Artem beat his hand on the drum. Again, Artem said that he liked this. It was interesting as I found myself standing and marching as I improvised on the clarinet, almost as though we were in a marching band, soldiers together. In this way the music seemed to reflect Artem’s dreams, his wishes. Shortly after this Artem began to yawn and to close his eyes, and I improvised a lullaby on the clarinet as he drifted off to sleep.

Session 2: Storytelling

When I arrived for the next session Artem lay in his bed and this time his mother sat on one side, his father on the other and a family friend was also sitting in the room. Through the interpreter I was told that Artem wished to play the guitar and the drum once again. He then wanted me to play the clarinet. As I improvised, Artem’s mother stroked his head, holding his hand and as he gazed into her eyes she told him a story. I will never know what the story was, but it struck me that her words and phrases seemed to reflect the musical phrases of the clarinet and the highs and lows of the melodic line seemed to be mirrored in the intonation of her voice. It was also remarkable that we ended the ‘story’ together. I have often wondered since that day about how it was possible for two people from entirely different cultures, speaking different languages, to connect so closely on a first meeting except through the language of music.

Following this improvisation, I asked through the interpreter if the family might like to sing a song in their native tongue. Artem’s father asked if he could play my guitar and tentatively he began plucking a melody line. It was at this point that the room began to glow, rather like candles being lit on a dark night as first Artem’s mother and then each member of the family and the interpreter joined in, singing with the guitar. As they sang, I wove a harmony on the clarinet, connecting and empathising without words. Once again, Artem and his mother gazed into each other’s eyes and she stroked his head. It was very moving, an acknowledgement of Artem’s cultural heritage and a brief piece of Ukraine in London.

Session 3: Goodbye

My third session with Artem and his family was to be the last time that I saw him. When I entered the room he seemed pale and lethargic. The room was full of family members, with his mother, father, two other adults and another child sitting around the bed. I asked Artem’s mother if she wished me to call the interpreter and she said strongly, ‘But music is universal, you can talk to me and I understand.’ I wondered if she wanted to keep this session between the family and myself. Maybe the interpreter would feel like an intrusion. Her comment also reminded me of the previous session when she and I had connected so strongly in the storytelling.

After I had sung hello to Artem, his father took the guitar and once again Artem’s mother began to sing a Ukrainian song. Just as in the previous session I took my clarinet and wove a harmony to support their music. This time I felt that I was supporting the family in their loss, the music enabling them to share together in their grief in a culturally appropriate way. As she sang, Artem’s mother became very tearful, choking on her words. Following the song she allowed me to comfort her and to acknowledge the pain of her loss. Following this exchange she asked me if I could play the Beatles song ‘Yesterday’. As we sang and played this symbolic song she gave an ironic laugh as the tears flowed. I then sang goodbye to Artem to end the session.

I was not aware at this point that this would be the final time I would see him and his family. I feel immensely privileged to have had the opportunity to meet Artem and his family at such a precious time. I believe that the choice of the clarinet enabled me to draw near to them and support them in their loss, especially when my relationship with them was so brief. Shortly after this session Artem and his family returned home where he ended his days in a hospice.

Finding a different voice

Henry Dunn

I first fell in love with the clarinet as a young boy, at the age of about eight or nine. Some family friends were having a musical evening at their home, and I heard someone playing the clarinet. I immediately decided that I had to learn, and fortunately my parents supported me in that aim. I worked my way through the graded exams, but wasn’t able to improvise, despite my love of jazz. That changed as an adult, and I discovered that I could improvise and create my own music, expressing myself through the voice of the clarinet. I now find that my playing in jazz informs and improves my playing in therapy, and vice versa, although the purposes are very different – the former to entertain, the latter to express emotion, no matter how unpleasant it may sound.

This ability to improvise developed on a working party at a beautiful Christian community in North Devon when I was about 20 years old – we were gathered round a piano, playing songs, and I suddenly found myself playing notes on the clarinet without really knowing where they were coming from. For this reason improvisation also has a strong spiritual element for me, reaching a very deep, unconscious part of myself. This in turn is reflected in the psychoanalytically informed approach I have to music therapy, which seeks to find the unconscious dynamics behind people’s musical expression. I find myself drawn to depth, musically, spiritually and psychologically.

When I was 30 I embarked on my music therapy training and found that the piano and the clarinet were equally valuable in my work. I find the piano helps most in providing structure and containment, but it feels, to me at least, quite a masculine instrument. The clarinet gives me access to a more tender, fluid, feminine voice, with a greater pitch range than my rather low singing voice. This can be particularly useful when working with people whose mother was absent or abusive. They can experience a maternal voice that is caring and responsive, expressing unconditional positive regard (Rogers 1957).

Although I use the piano a lot of the time, finding it very expressive and valuable, I sometimes observe a tendency to use it defensively, with it creating a physical barrier between the client and myself. It can also be connected with my expertise on the piano compared to that of the client, who might feel intimidated and unable to use the piano to express themselves. The clarinet, although also requiring expertise, doesn’t seem to have that effect, as it mirrors the voice closely and reveals a vulnerability in the therapist that the piano might not. If I become emotional in our shared music, this will affect my breath, which will affect my playing. My tone may crack or seem a bit wobbly, reflecting the way I feel. This is in response to the client’s emotion and can happen without conscious thought, in the moment. I feel that the clarinet is my voice in a way that the piano never could be, and that this vulnerability on my part gives the client permission to also become vulnerable. It is this sense of joint openness that can be so powerful in music therapy and is perhaps harder to achieve with verbal therapies.

The clarinet is also very portable. I can move around with it and not be fixed to the spot as I am on the piano. I can sit on the floor and play, or I can chase round the room playing it. It is also useful in environments where there is no piano or keyboard.

Case vignette: Julie

Julie, a woman in her 50s, was referred to me owing to her anxiety and her bipolar disorder. Not long into our work she was given a diagnosis of breast cancer, which spread to her spine. She loved to hear the clarinet, either played by me or in recordings that we listened to in order to aid relaxation. She particularly liked listening to Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto.

During our improvisations she played a variety of percussion instruments and requested that I play the clarinet. Sometimes she would stop for a while and just listen to me play. I found that I could respond very quickly on the clarinet to any changes of mood, tempo and volume, and it was easier to sit facing towards her than it would have been at the piano. Playing the clarinet seems to give a greater intimacy – it is more an extension of me than the piano, as it is my breath that is making the music, with less of a mechanical gap between the player and the resulting sound than on the piano. I could then non-verbally express care and compassion in a way that felt more powerful and warm than words alone.

Julie had been estranged from her mother for several years and did not want any contact with her. It occurred to me that the maternal sound of the clarinet was providing some kind of substitute for this. It also enabled me, as a male therapist, to provide an element of maternal function that would not otherwise be accessible to me.

I often use the clarinet to mirror vocalisations of clients who are non-verbal. The communicative vocalisations are reflected back in a more musical form, moving from mirroring to affect attunement (Stern 1985). I am taking the client’s emotional communication and transforming it in a way that is still recognisable but also distinctly mine. This sense of shared meaning, balanced by an awareness of the other, can be a crucial development in therapy. For clients with autism, this type of exchange can help to develop the ability to relate to another as a distinct and separate person who attends to, and responds empathically to, their emotional communication. In addition, the expressive qualities of the clarinet can encourage clients to move from a monotone voice to one with more variation in pitch and expressiveness. It can encourage non-verbal dialogue that is playful and creative, and that is able to convey a wide range of emotions.

I have also used the clarinet with children who have suffered trauma to the brain or were born with an underdeveloped brain. For example, I worked with a young boy who had nearly drowned, suffering hypoxia. He was left in a virtually comatose state. I played my clarinet to fit with his breathing and eye movement, and there was some small sense of reciprocation in the way his breathing and eye movement changed with my playing. I also worked with a six-month-old baby whose brain scan had not shown any activity. When I played the clarinet she seemed to come alive, her eyes showing life, a hint of a smile on her face. There seems to be a quality about the clarinet that is able to awaken even the most unreachable clients. Maybe this is connected with the maternal sound, maybe there is something about the vibrations it causes. With children who are deaf, or deaf and blind, I frequently play the instrument close to their body so that they can feel the vibration. This often seems to have a calming effect and can relax the muscles. Many people that I work with find the sound relaxing, sometimes falling asleep – the opposite of the awakening effect mentioned earlier.

In short, I would not want to be without my clarinet in music therapy sessions. The only time I would not use it is if the client showed an active dislike of the sound or if I felt there was a risk that a client might want to damage it, but this is not something that happens too often. The clarinet is my musical voice in therapy, so to deprive myself of it would be pointless and counter-therapeutic.

I used to dream of the perfect clarinet sound…

Amelia Oldfield

As a child I learnt to play the piano first. Then as a teenager I wanted to play an orchestral instrument so I could play with other musicians. I spent hours listening to orchestral recordings as well as to the Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra by Benjamin Britten, and quite quickly decided that I liked the sound of the clarinet best of all. As I was living in Austria at the time, I started learning the clarinet in Vienna, but luckily my teacher realised I would not be staying there for very long and started me off on the commonly used Boehm fingering system, rather than on the simple system clarinets that were still being used uniquely in Austria at that time. After a couple of years I moved to France, where I continued to have lessons, first at the Conservatoire in Montpellier, then at the Conservatoire in Aix-en-Provence from two clarinettists who happened to be brothers. Four years later I moved to Canada and had lessons at the music department at McGill University. By this time I had seriously fallen in love with the clarinet and it had become my first rather than my second instrument.

When I moved to the Guildhall School of Music and Drama to do my music therapy training I did not like the very different English clarinet sound my new teacher was suggesting to me. One day, as I was wandering down the corridor, I heard the most beautiful clarinet sound coming out of one of the practice rooms. I immediately knew this was what I was striving for and walked in to find the renowned Israeli clarinettist Yona Ettlinger. He agreed to teach me, and I continued having lessons with him, and then with his wife Naomi, for several years after I started working as a music therapist. I particularly remember the fortnightly Saturday master classes at the Guildhall, which usually led to dreams about the ultimate, perfect clarinet sound on Saturday nights.

I have always enjoyed using the clarinet in my music therapy clinical work. I love playing it, revel in producing as good a sound as possible, and feel I can convey emotion through my playing more effectively than through any other instrument. I have continued to play in various chamber groups and orchestras throughout my 34 years of music therapy practice. This keeps my own music and my passion for the clarinet alive, and provides me with inspiration for improvisations in my clinical practice. Conversely I have found that my regular use of improvisation in my music therapy practice has improved my tone and confidence when playing chamber music. I find I need to play, on average, about three evenings a week to maintain the control and flexibility of my embouchure in my clinical practice. If for some reason I don’t play my clarinet for a couple of weeks, I often notice that I start getting grumpy and irritable; somehow, I need to play to feel whole and complete.

Case vignette: Tim

Three-year-old Tim, who has a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, gets up from the piano, which we have been playing together, and wanders to the other side of the room. He has no speech, but glances at the clarinet on top of the piano and then at me. I know exactly what he is communicating to me: ‘Come on, do what you usually do, pick up your clarinet and walk around the room with me.’ As soon as I start playing the clarinet he grins broadly. We march around the room together and I improvise a tune to match our walking pace. Then he lies down on the floor and kicks his legs in the air. I play a version of ‘Row, row, row your boat’ while his mother holds his legs and sways from side to side. Occasionally I stop playing to join in with the singing, but incorporate low trills on the clarinet to add excitement when the ‘crocodile’ appears. We repeat several variations of the song and on the third time, when we leave a gap before the dramatic ‘scream’ at the end of the song, he makes a tentative vocal sound, looking quite surprised that he has done this. His mother looks at me and grins; we are both delighted that Tim is starting to use his voice.

In later sessions Tim masters the technique of producing a sound by blowing the recorder or a reed horn. This enables us to have clarinet and horn dialogues and further encourages Tim to use his voice.

For Tim the clarinet is associated with a moment in the music therapy session when he moves around the room and I take his lead and follow him while playing at the same time. This is particularly useful for Tim, who finds it hard to remain seated or focused on any one activity for very long. He has always been interested in the clarinet, making good eye contact and smiling whenever I start playing. Tim’s mother is proud of her son’s particular interest in this slightly unusual instrument. It is also useful for me to be able to alternate playing and singing because it means I can use words in the songs, but then continue the tune on the clarinet to maintain the musical line and Tim’s interest. Tim recognises the sounds of the words and can occasionally be prompted to vocalise himself, but he needs the clarinet sound accompanied by my movements to maintain his interest.

Case vignette: Ella

Figure 1.3 Listening to that special sound

Ella is also three years old. She has profound and multiple learning disabilities, is very restricted in her movements, has severe epilepsy and is partially sighted. She does not sleep well, so both she and her mother are often quite tired. She can sometimes move her arms and hands a little to strum the guitar, or to scratch or tap a drum. She will also occasionally vocalise. For Ella the high point of the session is usually when her mother holds up some wind-chimes for her and I play the clarinet. Like Tim, she will nearly always smile when I start playing, and will sometimes get very excited, kicking her legs and moving her hands towards the chimes. At other times she plays more quietly and both she and her mother look sleepy. I try to match her mood while improvising, keeping the melodic line flowing and ‘open’, playing in pentatonic or modal keys. I know that high notes, squeaks and glissandi often make her smile, while lower, legato phrases help her to relax. In addition, the fact that I can bend the pitch of the notes to match her vocalisations is often useful. Ella’s mother is also affected by the clarinet. Like Tim’s mother, she takes pride in Ella’s interest in this instrument and is always pleased when Ella becomes engaged and interactive.

Case vignette: Group

In my weekly group of five children with a variety of emotional difficulties (Asperger’s syndrome, eating disorders, Tourette’s syndrome, attention deficit disorder) the children eye my clarinet case with suspicion. I have just suggested that there might be a rabbit in the case… but after some discussion allow them to convince me it must be a musical instrument. We establish that it is a clarinet and I ask them to guess how many pieces it consists of. One little boy who is six and has been to the group before shouts out ‘seven’ and is delighted when I put the instrument together and show he is right. I play a short tune, the children listen and I then suggest that they shut their eyes and guess how many notes I have just played by putting their hands in the air and showing a number.

Later in the group, my music therapy student who is a violinist gets out her violin and we form two teams, half the group play the xylophone when they hear the violin, the other half play the metallophone when they hear the clarinet. At first we take it in turns to play to make it easier for the children, but then we overlap and intermingle so they really have to listen.

Here I use the children’s interest in a slightly unusual instrument packed in a box to gain their interest and enthusiasm. The fact that it is a single-line instrument makes it easy for the children to distinguish and listen to how many notes I am playing. It is then possible for them to listen both to the violin and the clarinet and play as a group.

Clarinet characteristics in music therapy practice

An attraction to the particular sound of the clarinet

It was generally felt that many clients were attracted to the sound of the instrument and would either specifically request it, or show pleasure when it was played. One clarinettist wondered whether the clarinet sound was a maternal sound, or whether it caused special types of vibrations. For some clients it was particularly important that the clarinet was a ‘proper’ instrument rather than an educational school percussion instrument.

Eliciting vocalisations

All of the clarinettists felt that the tone quality of the clarinet is similar to the voice. The clarinet was successfully used to encourage clients to vocalise and then to have non-verbal dialogue with the client using both the clarinet and the voice. The instrument was also used to mirror intonation and match the speaking voice. In addition it was mentioned that the expressive qualities of the clarinet could help clients with monotone voices to introduce more variation in their spoken voices.

Mobility

All four clarinettists mentioned the fact that playing the clarinet in music therapy sessions allowed them to be mobile, either to walk around the room with the client, or to be by their bedside or on the floor. This is also mentioned in the existing literature (Salkeld 2008, p.151 and Oldfield 2006a, p.34).

The therapist’s own instrument

All the clarinettists felt it was important to play their own instrument and that some clients particularly valued the fact that the clarinet was the therapist’s personal instrument.

Playfulness

Three clarinettists mentioned using the clarinet to be playful with their clients, running around the room, playing ‘peek-a-boo’, or accompanying movements in a humorous way. One clarinettist mentioned engaging a group of children by getting them to guess what was in the clarinet case and how many pieces it was divided up into.

A physical link between the therapist and the client

It was mentioned several times that the clarinet can be played directly opposite the client, which can be an advantage when attempting to interact or communicate. Clients would sometimes touch the bell of the clarinet to feel the vibrations, and the instrument could provide a physical link between the client and the therapist.

Combining the clarinet with other wind instruments such as reed horns

Clarinet playing can provide an incentive for clients to master the technique of blowing, and then create an opportunity for turn-taking and exchange. It helps that wind players have to stop playing at times to take a breath, and these pauses can then be used to dramatic effect. This is clear from the case material in this chapter, as well as from the previous literature by Oldfield (2006a).

Associating the clarinet with specific events

The clarinet was often specifically chosen by clients and in some cases associated with clear events, such as an activity involving walking around the room. Clients and relatives took pride in this definite choice. In one case the clarinettist was able to link into the child’s past interest in becoming a soldier by marching around the room playing the clarinet. In another case the client had a particular preference for a famous piece of clarinet music, which the therapist was able to explore in the session.

Accompanying breathing or breathy sounds

This was mentioned as a special feature of the clarinet, enabling the clarinettist to follow the client’s breathing and use a combination of breathy clarinet tones and vocalisations to play with clients with very limited abilities.

Eliciting responses through special effects

Playing with the mouthpiece on its own, glissandi, bending notes and squeaks were all mentioned as ways to surprise, engage or be humorous.

Characteristic tone colour of the clarinet

The fact that the clarinet has a very distinct sound allows music therapists to accompany chaotic synthesiser music or weave a melodic line under a sung melody. One music therapist wondered whether the distinct clarinet sound made it easier for children with a weak sense of self to distinguish between themselves and the therapist. The specific clarinet sound was also used as a contrast to the violin sound in a music therapy group to encourage children to listen, and follow either one or the other.

References

Oldfield, A. (2006a) Interactive Music Therapy, A Positive Approach to Melody. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Oldfield, A. (2006b) Interactive Music Therapy in Child and Family Psychiatry – Clinical Practice, Research and Teaching. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers

Rogers, C. (1957) ‘The Necessary and Sufficient Conditions of Therapeutic Personality Change.’ Journal of Consulting Psychology 21, 2, 95–103.

Salkeld, C. (2008) ‘Music Therapy after Adoption: The Role of Family Therapy in Developing Secure Attachments in Adopted Children.’ In A. Oldfield and C. Flower (eds) Music Therapy with Children and Their Families. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Stern, D. (1985) The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New York, NY: Basic Books.