Читать книгу Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? - Jo Tomlinson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

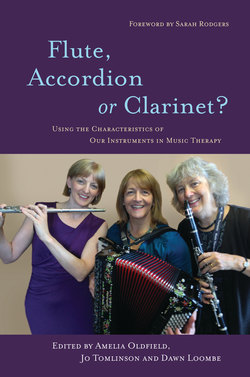

ОглавлениеForeword

David played the harp and Saul was refreshed; a simple and true statement of the power of music.

Music has accompanied every human journey since the historical record began – not surprising, perhaps, in the light of the planet’s deep and connected natural sounds and rhythm.

In this book, music therapists tell us about their personal journeys with their first instruments and how they have been able to use these instruments in clinical music therapy to accompany clients on their journeys.

Although I am not a music therapist, the power of music came home to me in a profound way when I lived for two years in Sierra Leone, working for VSO (Voluntary Service Overseas). As a very new graduate, I was responsible for training music teachers. My work took me ‘up country’ to native schools in the African bush where, notwithstanding the very English-based curriculum, I was privileged to experience the depth of meaning brought to people’s lives through their engagement with the indigenous music. Here, music meant communication, conversation, approval, achievement, recognition, rite of passage, as well as work, community, relaxation and entertainment.

That music could be so intrinsic and specific a part of life – fundamental, essential, connecting and completing – opened my eyes, ears and mind to a relationship that already had my heart! My musical experience began with my father who played saxophone and piano in dance bands and my own formal training started on the piano at the age of five. Bassoon, flute, guitar and cello followed and, later, all were eclipsed by composing and conducting. Music was central to my childhood, making its claim on me through family, friends, education and recreation – all adding pathways on the map of my adult musical life.

In the same way, almost all the music therapists writing in this book trace their passion for their first instrument and for music in general to childhood or to family experiences.

My career in music has led me through many fascinating encounters, not least of which was a commission for the City of London Sinfonia for a cross-cultural work I composed and conducted called Saigyo, named for the Japanese warrior poet on whose work I drew for inspiration. The scope of this commission embraced working with many different kinds of musicians in many different circumstances, from the Japanese shakuhachi player whose instrument featured in the new composition, to the school children who developed projects around the new piece and the community groups with whom I worked to produce a pre-concert performance in Peterborough cathedral.

A special needs group, an adult recorder ensemble and a samba band met under my guidance, not only to work together but also to perform as an integrated creative entity. This unusual combination immediately threw into sharp relief very different approaches to music and contrasting but complementary aspects of musical experience, from emotional directness, to intellectual exploration to sheer physical immersion.

As we work-shopped our ideas, the participants played not only as their existing groups but also cross-fertilised in subgroups of threes. There were challenges of communication, of technical ability, of aspiration, and of interaction. Those whose musical repertoire was usually more complex found themselves seeking simplicity and those whose experience was more simple were drawn to greater complexity. Those whose musical interest was focused on rhythm experienced the joy of sonority and those who were more accustomed to restricted practices broke out into extremes of dynamic, range and emotion.

This was a wonderful, touching and highly instructive experience. Music was the differentiating element and it became the combining force. Similarly, chapters in this book show that while each instrument has its own characteristics, ultimately, it is through the music-making itself that interactions can develop and changes can occur.

Music is nothing more or less than a disturbance of the air – the very air around us without which we would not exist. Music inhabits this world of vibration by pipe, by string, by skin, by block, and this in turn is what resonates with the human being.

This I believe is one of those unsung secrets, one of those truths that we as musicians all know and yet somehow do not often articulate and it is the reason why this publication is so important. To hear from musician practitioners their experiences of opening up the love, knowledge and intimacy of their first instrument to those they are there to help, is a joy.

For me as a composer, my music must touch an emotional chord, provoke an emotional response, leave an emotional resonance. The essays in this book make a valuable contribution to the understanding of how we invite and make that emotional connection with music. I wholeheartedly recommend that Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? Using the Characteristics of Our Instruments in Music Therapy is disseminated beyond the realm of music therapy and is read by as many musicians as possible.

Sarah Rodgers,

Composer and conductor