Читать книгу Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? - Jo Tomlinson - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

The Piano Accordion

Contributors: Susan Greenhalgh, Dawn Loombe

(introduction and case vignettes – these case vignettes

also include case material by Harriet Powell,

Bert Santilly and Michael Ward-Bergeman)

Introduction

Accordions and their close relatives, the harmonica, melodeon, concertina and bandoneon are all descendants of the Chinese sheng – an ancient mouth-blown free-reed instrument consisting essentially of vertical pipes and dating from around 2700 BC.

Early accordions first appeared in Europe in the 1820s and in the USA slightly later in the 19th century, though there are conflicting accounts as to exactly where, when and by whom the original accordions were built. The first accordions to arrive in Britain were actually melodeons (button accordions, each button producing two different notes on the push and pull of the bellows) and were used by music hall performers, Scottish folk musicians and later by English Morris dance musicians.

Accordions with piano keyboards were developed in 1852 by Parisian Jacques Bouton and by the beginning of the 20th century the accordion’s bass keyboard had been developed sufficiently to provide accompaniments in all keys. These relatively new piano accordions gained popularity in the UK from the late 1920s, when they began to be imported from Italy and introduced into dance bands to produce more authentic-sounding tangos. Pianist George Scott-Wood imported a piano accordion from Italy in 1927 and became Britain’s first professional accordion player. The 1920s and ’30s also saw the rapid expansion of cinema, with accompanying organ entertainment – usually on a Wurlitzer or Compton organ – and ‘the arrival of the piano accordion in Britain’s music stores in large quantities from 1927 onwards…allowed the possibility of owning and playing what was virtually a small-scale theatre organ capable of playing all the popular songs and tunes of the time’ (Howard 2005, p.16).

However, from the mid-1950s the accordion’s popularity began to slump and it quickly became a very unfashionable instrument. Rock and roll music had introduced the guitar to popular culture, and the guitar was ‘cool’, relatively inexpensive (especially compared to the accordion), accessible and easy to play; learning to strum a few simple chords allowed the playing of many pop songs of the day. Young people were keen to emulate admired guitar heroes and a different kind of pop music emerged. At the same time, there was a general decline in the popularity of variety shows, and the accordion became very passé, generally an object of ridicule in the world of music.

In recent years, though, the accordion has seen a rebirth of interest, with an increasing prevalence in pop and rock music, television themes, advertisements and film scores, as well as becoming a more accepted instrument in the classical world. In addition, the interest in World music has provided new and eclectic styles of accordion music, which have brought new audiences to the accordion.1 The resurgence of ballroom and Latin dancing, particularly from television series such as Strictly Come Dancing, has raised awareness of traditional dance styles and also the use of the accordion for tangos, waltzes and polkas.

In the classical world, works have been written for the accordion by Tchaikovsky, Prokofiev and Shostakovich, and the music of Bach and Scarlatti along with many others has been transcribed for the modern accordion. Increasingly, composers are writing classical music for the accordion and including accordion parts in orchestral scores and group compositions.

For the purposes of this chapter, accordion refers to the piano accordion. The accordion is defined as a hand-held free-reed aerophone, in which the sound is produced by tempered steel reeds that vibrate when air is forced through them by a set of bellows. On one side of the bellows there are rows of buttons or a keyboard on which the melody is played, while on the other side there are buttons for the bass notes and chords (Wade-Matthews and Thompson 2002).

The accordion is held close to the player’s chest, supported by means of straps. The accordionist’s right hand plays a piano keyboard, usually (but not always) the melody. The left hand plays a series of buttons producing single bass notes, chords or a combination of single notes and chords, usually a bass accompaniment.

Most people are aware that there are rock, classical, Western, jazz and folk-style guitars but few realise that there are at least as many types of accordions. Just like the guitar, accordions are built for different styles of music and have a variety of temperaments or tuning schemes.

Accordions are usually classified by the number of bass buttons they have, ranging in size from small, simple 8- or 12-bass instruments to complex accordions of 120 basses or more.

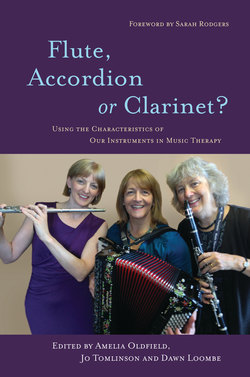

Figure 2.1 The piano accordion

In addition, most accordions have switches or couplers that allow the use of different combinations of reeds (rather like the stops on an organ), and these can give the player great scope in pitch range and quality of sound. The larger models, although superior in sound quality, can be heavy and unwieldy, while a smaller instrument might not give a satisfying enough sound, or enough musical scope for the therapist.

Accordions are also classified according to their timbre:

•Musette accordions have a characteristic shrill timbre, which is produced by a particular tuning of the three middle-voiced reeds of the instrument. The two outer reeds are tuned slightly off-key (one slightly sharp and one slightly flat of the perfect pitch reed) to produce this typical accordion sound, favoured by players of traditional French, Scottish and Irish music.

•Dry-tuned or straight-tuned accordions have the reeds tuned to produce a purer, more harmonious sound required for modern music, and particularly tango and other Latin styles. It is also used for playing classical music.

•Chambered or Cassotto tuning gives the particular mellow accordion sound preferred by jazz accordionists. This is achieved by engineering the reed blocks into chambers, which add tonal warmth. This is very distinctive and a development that has contributed greatly to the maturing of the accordion as a classical musical instrument. However, accordions with tone chambers are much more expensive to buy and are also much heavier instruments.

These different mechanisms allow the accordionist great musical scope in terms of pitch and quality of sound (by means of the reeds and couplers) and also dynamic control, touch, phrasing and musical expression (by means of effective use of the bellows).

The accordion has always been close to my heart

Dawn Loombe

The piano accordion is my principal instrument and provides my identity as a musician. It is therefore the instrument with which I am most likely to communicate effectively. I am passionate about the accordion, having played since I was ten years old. My school friend had pestered her parents to buy her a small accordion, having seen an accordionist playing Irish jigs and reels. I was already learning the piano and violin and I became intrigued by her fascinating instrument, which seemed to me to be alive and so different. After trying her small piano accordion, I too was hooked. My father bought me a small second-hand instrument and I began taking lessons. I also played bass accordion and then first accordion in the Norwich Accordion Orchestra in the 1970s and 1980s. My friend and I grew up together playing accordion and we still get together to play now. I have been performing as a solo accordionist and community musician in various bands and ensembles for around 40 years.

There is something special about the way the accordion becomes part of me and moves with me as I wear it and the way that the bellows can be used to express exactly what I want to say with a piece of music; it is literally always close to my heart.

I am often asked to play musette accordion pieces for French-themed events, traditional Neapolitan tunes for Italian weddings, with ceilidh bands for Scottish or English traditional dancing, at outdoor carnivals and village festivals, in local pubs and folk clubs, European folk and classical music with a multi-instrumental trio, Klezmer tunes (together with clarinet and violin), Piazzola tangos, German drinking songs with an ‘oom-pah’ band, polkas, Russian folk songs, Cajun, Tex-Mex, jazz standards, or to accompany singers. Many of these styles of accordion music and particular techniques I have learned have – at different times and in many diverse ways – found their way into the music I play with clients in music therapy sessions and influenced my work as a music therapist.

Of course, I do use a variety of instruments in my clinical work and I make choices depending on the needs and likes of the clients with whom I work. However, I have found that there are some unique aspects of the accordion that can be particularly useful in music therapy, and since training at Anglia Ruskin University in 2003 I have been thinking about these features. My MA dissertation (Loombe 2009) explored the use of the accordion in music therapy through my own casework in various settings, as well as a literature review and interviews with other accordionists also using their instruments in music therapy.

Figure 2.2 Music therapy with the accordion at the Child Development Centre, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge

As other music therapists have found, I have a therapy instrument, which I use in sessions rather than risking the use of my more precious performance accordion. However, there is always a compromise, and it can be a challenge to find an accordion with good-quality reeds and a satisfying sound that is small enough and suitable for music therapy use, yet not too expensive or heavy.

Another challenge when using the accordion in music therapy results from the wearing of the instrument on my body: it can sometimes be difficult to remove quickly and safely. The bellows straps need to be fastened top and bottom, to prevent the bellows opening as I take it off, and there is usually a backstrap to unclip before putting down the accordion safely. For this reason, I never use my accordion where I might be physically compromised in a session, where either the instrument or I might be at risk or where a client has challenging behaviour (for example where I need to be physically ready to respond to prevent a child from harm).

My music therapy accordion is a medium-sized, straight-tuned accordion (without the shrill musette sound that typifies French or Scottish accordion music). This is mainly because it is my preferred accordion tuning and also because I find that it is the single reed sound that most resonates with people; the accordion sound that allows me to respond immediately and most effectively. I rarely use the tremolo reeds (unless I want to produce a particularly strident sound for dynamic effect), as I find the single-reed couplers much more responsive and useful for a variety of musical styles.

Accordionist Santilly (2009) uses a 120-bass accordion that has both straight-tuning and musette-tuning, giving him a diversity of accordion timbres within one instrument in all aspects of his work as both teacher and performer. Santilly has found the purer single-reed sounds to be more useful in his school work than the tremolo or musette couplers, particularly in working with children with autistic spectrum disorder. We have both noticed that many children find the accordion’s musette sound particularly painful, such that they recoil, sometimes putting their fingers in their ears. This is most noticeable with the three-voice musette tuning, because this has two different sets of vibrato, meaning that the points of coincidence for the sound are very complex; this can be too uncomfortable for those with very sensitive hearing, for whom the harmonic beats can be very prominent. Santilly also switches out the accordion’s musette reeds to use just the straight tuning, which can be more sympathetic to sensitive ears. Michael Ward-Bergeman (2009) also noted how the pure single-reed tone resonated in his therapeutic work, commenting that this resembles a basic sine wave – the simple building block of all sound. He said that he uses the dynamic range of his accordion to ‘try to tune in to frequencies people are resonating with’.

Use of the accordion in music therapy

There has been little mention of the use of the accordion in music therapy literature. Limited reference to the use of the accordion – mainly as a useful portable and harmonic instrument – have been made by Bang (2006), Gaertner (1999) and Aldridge (2000 and 2005), among others. However, two authors in particular – Harriet Powell and Ruth Bright – have explored the use of the accordion in music therapy in more depth and their findings are examined here.

Harriet Powell (2004a) begins with a humorous look at the accordion, acknowledging its iniquitous image using Gary Larson’s famous cartoon. In his Far Side sketch, described by Powell, Larson depicts St. Peter handing a harp to an angelic figure at the gates of Heaven, saying ‘Welcome to Heaven. Here’s your harp’. Whilst at the fires of Hell, accordions are being handed out with the message ‘Welcome to Hell. Here’s your accordion’. Powell acknowledges this particular image of the accordion before explaining how useful this instrument has been in her own music therapy work. Prior to training as a music therapist, Powell studied piano and organ and worked in community theatre and music workshops, where she found the accordion a useful instrument with all ages. When she began training as a music therapist her supervisors did not discourage her use of the accordion, but there was never any time spent on how to use it effectively. Despite this, Powell has continued to play her accordion successfully for many years in her clinical work with older people with dementia. She also uses it in her Nordoff-Robbins work with children and adults with learning disabilities.

Powell (2004a, p.21) lists the accordion’s advantages, particularly: its portability; its ability to be played in close proximity to her clients; the way that she can provide a left-hand accompaniment whilst dancing and singing with a client; and the accordion’s ability to sustain and hold. She says the accordion is a versatile and useful instrument in music therapy and that she feels it becomes a part of her, allowing the freedom ‘to be with the person physically and musically’.

In one of her case studies, Powell describes the particular importance of the accordion for Peter, a 70-year-old man in the early stages of dementia, in a group session:

When I played the accordion he began to cry and said that his brother used to play. He proceeded to sing ‘Alexander’s Ragtime Band’ which he remembered his brother playing. Then I offered him the keyboard of the accordion to have a go. He played a few notes tentatively and as I provided the rhythmic and harmonic structure on the buttons with my left hand he became bolder. He played with vitality, melody and increasing virtuosity with glissandi up and down the keyboard to the cheers of encouragement and appreciation from the rest of the group. He still had tears in his eyes with a broad smile on his face. (Powell 2004a, pp.20–21)

With James, a frail and elderly ex-miner suffering from confusion, memory loss and depression, Powell (2004b) explained how their musical relationship became more interactive over time, with James playing harmonica and Powell playing her accordion. These sessions helped James to free himself from isolation, rediscover his musical skills and regain a sense of identity. Powell’s use of accordion seemed to have resonated with James, who had played accordion and harmonica in his youth; indeed she mentions that there were times when he corrected her accordion technique (2004b, p.174). It is also relevant that the accordion and harmonica are related free-reed instruments, which provided another link between the two players. Bright (2007) believes that it is essential for all music therapists to play a portable instrument. She specifically mentions the accordion as being ideal for work in dementia and writes:

I myself play a piano accordion, sitting at the same level as the individual, making direct eye contact and playing appropriate music for each in turn. (I got an accordion originally for work in a children’s ward of a big hospital and the two situations are not dissimilar – each child wanted different music, played to him or her personally). (Bright 2008, p.3)

Bright (1997) also describes a particular piece of work in hospital with a stroke patient, where she was working ‘to change the cycle of fear and pain’. A physiotherapist was working simultaneously with this particular patient, facilitating passive movements of the woman’s arm to prevent her shoulder from becoming frozen and painful. As the woman saw the physiotherapist lift the arm she screamed in pain, but when Bright played accordion music to her on the other side, ‘the arm could be lifted…without any awareness of pain’ (Bright 1997, p.142). It could be argued that the strength and self-contained harmonic completeness of the accordion were particularly effective here at engaging the attention of the patient and distracting her from the pain.

In another case, Bright (2006, p.4) describes a piece of group work involving an elderly man who had recently undergone an above-knee amputation. When group members were asked to choose favourite pieces of music, this man chose a romantic waltz, which was important to him from his courtship. As Bright played his music on her accordion the man wept, saying ‘I can’t dance any more!’ The music represented both movement and dance, areas of significant loss to this man who had recently lost a leg. Bright goes on to explain how the dance music then provided a focus for grief-work over the life changes endured by this man.

Bright considers how to choose the best instrument in palliative care (Bright 2002, p.73). She suggests that the therapist should choose an instrument on the basis of her own preference and skill but also crucially, taking into account the preference of the client and suitability of the instrument for the patient’s capabilities. Bright describes several specific instruments that she finds useful in this work, and again she values the accordion, explaining that it:

Is useful because it gives a clear melody that is easily heard even by those with partial deafness, who can touch the instrument, feeling vibrations to support what is heard; player and listener are in eye contact and in close proximity, and the instrument brings back varied memories. I have been told of church services and bush dances, the accordion being used for both. (Bright 2002, p.73)

Case vignette: The dancer

Dawn Loombe

In a case described by Harriet Powell (2009), she met an elderly lady with dementia sitting on a chair in the corridor of the care home. The lady soon became engaged with Powell’s accordion music and stood up to dance. Powell found that holding the lady’s left hand with her own right hand was not quite supportive enough, so she guided the lady’s right hand to hold on to the accordion bellows. Powell and the lady were dancing face-to-face in this way for several minutes, with the accordion between them. Importantly, the lady’s keyworker then arrived and took the lady’s hands to dance and sing with her, freeing Powell to play more in support of their dancing. The lady was very engaged with both the accordion music and her keyworker and they danced together for a while. Powell explained how significant this was, as the lady and her keyworker had needed to work on developing their relationship and this gave them an opportunity to connect. The accordion was a key feature in providing this breakthrough. Powell commented that in her opinion, no other instrument is as good as the accordion is, in dancing with older people.

Case vignette: Eva’s hymn

Dawn Loombe

In a long-standing piece of work in a residential home for people with dementia, I worked with a group of four elderly residents (all aged over 85 years) with severe dementia, in a small private room. All of the group members were in wheelchairs and were very frail. They had few remaining verbal skills and could often be very confused and agitated. Usually, at least one member of the group would be unable to come to music therapy because they were too unwell; and if they did come, they would often fall asleep in their wheelchairs and could remain asleep for the whole session. This group was no longer able to take part in the home’s organised activities, owing to the advancement of their dementia. The staff valued this music therapy group, as it provided important opportunities for these patients to interact, to engage in holding and playing instruments, and to sing or join in with musical activities.

The accordion was of great value in this setting; familiar tunes from the war era, or hymns and organ pieces often elicited responses and it was possible to get very close to individuals to capture the brief moments when they were able to participate. As well as sharing percussion instruments, the keyboard of the accordion could also be offered to an individual to play a solo; the piano keys being relatively easy to press down, offering less resistance than actual piano keys and the therapist remaining in control of the bellows and the left-hand accompaniment.

In one very memorable session with this group, 95-year-old Eva began to sing the hymn ‘Now the Day Is Over’. As she did this, she moved her fingers in the air in front of her, as if playing the piano. I quickly moved close to her, to allow her fingers to touch the accordion keys. Eva found the middle C on the accordion keyboard with her right thumb and her other fingers followed. I soon realised that she had learned this hymn on the piano, or perhaps the organ, as she suddenly became more animated and said ‘How does it go?’, fumbling for the notes. Gently I began to sing the hymn with her. Hesitantly, Eva found the starting note and began to sing, with increasing confidence as she picked out the melody:

Now the day is over,

Night is drawing nigh,

Shadows of the evening

Steal across the sky

Jesus, give the weary

Calm and sweet repose;

With thy tend’rest blessing

May our eyelids close.

We played and sang the hymn again together and this time I provided an organ-like, chordal bass accompaniment on the accordion with my left hand. When Eva had finished, she looked up at me, smiling in a brief, shared moment of connection. It was then that the poignancy of the lyrics suddenly dawned on me. All of the other group members were now fast asleep and seemingly oblivious to our playing.

The accordion’s portability, its ability to be shared in this way and also its organ-like sound were all important aspects of this particular piece of work. The interaction could not have happened in the same way with a piano, as even if there had been space for one, it would have been too remote to engage Eva. A guitar, violin or clarinet could not have provided the same complete organ-like sound to accompany this hymn; and these instruments are not able to be shared in this way. Even a portable keyboard would not have provided the same element of intimacy and sense of connection.

Case vignette: Brenda’s fears

Dawn Loombe

I worked with Brenda, a lady with cerebral palsy, in a residential home. Brenda is non-verbal, in her late 40s and, although she seemed cognitively able, was physically very restricted in her movements and used a wheelchair. She was referred to our music therapy group, as she loved music and had shown a particular liking for both the harmonica and the accordion. Although Brenda was physically unable to hold a harmonica, when her helper held it up in front of Brenda’s mouth, she was able to move towards it, blow into it and make a pleasing sound to accompany the group’s playing. Brenda had a large collection of accordion CDs in her eclectic mix of recorded music and often became animated when listening.

However, she had never seen anyone play an accordion, and when presented with the actual instrument as I put it on my body, she unexpectedly became very upset. Her carers and I were initially quite shocked at this but we worked through it, explaining how the accordion works, helping Brenda to understand how it is played, giving her time to feel it and warning her when I was about to pick it up to play, so that she would not be too startled. I wondered about the reasons for this with my supervisor, and in a later session when I explained to Brenda and the group how much I enjoy playing the accordion and that wearing it ‘doesn’t hurt me’ she suddenly became totally relaxed and began again to enjoy my playing of her favourite accordion tunes.

The staff at the care home and I wondered whether Brenda viewed the instrument as a piece of medical equipment worn on the body, in a similar way to some of the medical paraphernalia she had witnessed in her life. I continued to work with this group for some months and there seemed to be no issues with the accordion after that; in fact, Brenda really loved joining in with our playing of authentic accordion jigs and reels.

This case made me consider exactly how and when I introduce the accordion to different client groups and to acknowledge others’ preconceptions and expectations of the accordion and the music traditionally associated with it.

I have also found the accordion extremely useful in my work with children who have a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, for whom the accordions buttons, keys, couplers and bellows seem to have a particular attraction. Alvin (Alvin and Warwick 1978) wrote about the autistic child’s interest in geometric shapes, which is reflected in his behaviour towards certain musical instruments, for example running his finger round the tambour, following the parallel lines of strings on the violin or autoharp, and building constructions of drums or chime bars. This first perceptual contact with the instrument is an important non-verbal, physical communication.

With the use of the accordion, it is significant that the therapist is wearing the accordion and operating the bellows, meaning that the child has to interact with the player, as well as the accordion. This promotes good eye contact, as both face each other with the accordion between them. Also, this eye contact does not need to be too intense for the child, as he can briefly look at the therapist and then back at the instrument. It is possible to readily explore basic concepts, such as on–off, stop–go, fast–slow and up–down, whilst playing together. It is also sometimes useful to be silent, and this can easily be effected by keeping the bellows closed. This stopping in silence can encourage the child to interact with the therapist to restart the activity. While the therapist has general control of the instrument and can play to musically support, she can also offer a child some aspects of the playing, or control of her playing, allowing the accordion playing to be shared. This can develop into interactive improvised music, using the accordion sounds and vocalisations.

The ability of the child to physically feel the instrument change shape and move has also been an important aspect of Bert Santilly’s work with children (2009). He talks passionately about the accordion being a ‘visually arresting instrument’, and both Santilly (2009) and Michael Ward-Bergeman (2009) highlight the important characteristic of ‘what you see is what you hear’; that is, when you hear a long accordion note, you also see it visually and simultaneously as the accordion bellows expand or contract.

Case vignette: Robert and the sensory aspects of the accordion

Dawn Loombe

Four-year-old Robert, who has a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder, received weekly music therapy sessions at the Child Development Centre in Cambridge and attended with his father for 11 months. Robert was extremely interested in the accordion from his very first session. At first, he would touch each part of the instrument, feeling the different textures of the bellows, the hard outer casing, the buttons, keys and switches. He marvelled as the bellows opened and closed (as I used only the air valve button) to produce a faint hissing sound, which I imitated vocally and he copied. Robert would press down an accordion key or button and I would respond by singing the note he played. He would then look up at me briefly before trying a different note and immediately looking back at me for a reaction, visibly pleased when I also sang this note.

He repeated this cause-and-effect game many times, sometimes running away excitedly before running back to play another accordion note for me to sing. Sometimes I waited a second or two before offering a vocal response, and he would watch my lips intently, waiting for me to sing, often bursting into a fit of giggles when I again vocally reflected his sound. This was a favourite game in sessions and Robert enjoyed this element of control.

In later sessions, Robert began to vocalise more freely with me, and his verbal language developed sufficiently for him to be able to request specific instruments or favourite games. Robert enjoyed watching the accordion bellows changing shape, following their patterns with his hands. He also noticed the colours: when the bellows opened, shouting ‘Red!’ as this colour was gradually revealed by the opening bellows – and this colour would disappear again as the accordion bellows closed.

Robert’s parents were pleased with his responses in music therapy and often mentioned an absence of what they called ‘stimming’ (his repetitive and isolated self-stimulatory behaviours) and more interactive, playful communication in our music therapy sessions. His father commented that the accordion is visually interesting, has many different surfaces to touch, a variety of sounds to explore, and buttons and keys to press. He thought that what particularly attracted Robert to the accordion was its complexity. Robert also brought his own small toy accordion to sessions and we regularly improvised accordion duets together, which seemed to be very satisfying for him.

Figure 2.3 Dawn and a visually-impaired little boy dance and play their accordions together in his music therapy sessions at the Child Development Centre

Case vignette: Kieran initiating interaction

Dawn Loombe

Five-year-old Kieran, who has profound autistic spectrum disorder, was also immediately extremely attracted to the accordion. For him, the most interesting aspect seemed to be the way the bellows moved in and out. I picked up on his interest by keeping the bellows tightly closed and building anticipation by singing slowly ‘1… 2… 3… OPEN!’ before playing a long drawn out G7 chord as the bellows opened wide. Then ‘STOP!’, briefly waiting with bellows open before singing ‘1… 2… 3… CLOSED!’, playing a loud C chord until the bellows were completely closed. Kieran responded extremely well to this; laughing excitedly and vocalising. He soon realised that he could sing the phrase ‘1… 2… 3… OPEN!’ to make this happen himself and began to initiate this game, singing and watching for my reaction. He would hold the bellows, feeling the vibration and supporting them to open and close with me. Kieran rarely talked and generally found interaction difficult, so for him, this was a first step towards positive communication.

The game then expanded gradually to singing some of his favourite songs together with an accordion accompaniment. Kieran seemed very aware that the bellows changed direction when breaths were taken. He also began to conduct my accordion playing, shouting ‘LOUD!’ or whispering ‘Quiet…sssshhh’ and ensuring that I responded appropriately. Modifying the volume is easy to do on the accordion, using the bellows, and this can also be visually exciting. I continued to work on sharing this element of control and increasing Kieran’s awareness of turn-taking and this was important in encouraging his social interaction both in and out of sessions.

Figure 2.4 Kieran interacting with the accordion

One of the characteristics of the accordion is the extent to which the player can vary the volume of a note whilst sustaining it. An accordion note (or indeed a chord) can begin very quietly and increase in volume, either suddenly or gradually. In fact a note or chord can have a series of peaks. Conversely a note can begin loud and then quieten, suddenly or very gradually. This makes the accordion sound more, as Santilly (2009) proposed, ‘animal-like; more like a voice’. Some wind or stringed instruments can do this in a limited way but the accordion is the only polyphonic instrument that can do this; the accordionist has the choice of varying the volume either with a single note or with several – and also has the option of using his own voice at the same time. The accordion can appear alive because it moves and breathes with its player and can recreate natural sounds in a manner that is unique among musical instruments.

In some settings it might be useful simply to use the accordion bellows to breathe, perhaps to reflect a quiet feeling in the room, or to match a client’s breathing. This can be done by simply operating the air valve button to use the bellows (without sounding notes by pressing keys or buttons). Both Bert Santilly (2009) and Michael Ward-Bergeman (2009) have explained how they had also used their accordions to reflect breathing in this way. Ward-Bergeman said that for him, the most important feature of the accordion is its ability to ‘breathe and to connect with life. The accordion’s bellows are like a giant lung and can communicate something we all have in common – breathing’.

Case vignette: Breathing together in music therapy

Dawn Loombe

Whilst training as a music therapist, one of my first placements was at a day centre, working with a group of six teenagers with profound and multiple disabilities. All of the group members were in wheelchairs and all were non-verbal, although most had the ability to vocalise. Some were visually impaired and one was hearing impaired. All had complex needs and all except one of the group were unable to hold any of the instruments or beaters.

This group had not had music therapy before, and it was apparent from my first appointment that this centre receives very few visitors, other than the health professionals working with the young people. The music therapy sessions were therefore eagerly awaited. Much was expected of the music therapy, and the staff prepared for the sessions diligently, ensuring that each member of the group had finished eating, had their requisite personal care and medication and that their wheelchairs were all positioned in a perfect semicircle, awaiting my arrival. On the day of the first session, I felt an incredible pressure to do something amazing with this group. I was a student on my first placement and I was extremely nervous.

The staff sat at the sides of the room, having put the box of percussion instruments in the centre. My chair was waiting for me, facing the semicircle of young people. Everyone was quiet. What should I do? What could they do? I looked around; in fact everyone looked slightly wary. I took a deep breath and started to sing a simple welcome song, just using my voice. There were a few slight movements but no sound. Then I realised that there was a faint sound – the sound of breathing. I could hear several different breathing patterns and a barely perceptible murmuring. I picked up my accordion and without really thinking about it, I used only the air valve to open and close the accordion bellows to breathe with them. I said what I could hear in the room and reflected the different breathing patterns of each person with the accordion bellows. I moved around the group, slowly weaving in and out of the chairs with my accordion, noting their individual sounds. Some of them moved their head towards me and there was definite recognition of what was happening. The sounds were slow and gentle. Gradually, there was more murmuring and some other vocalising, and I began to play some soft breathy sounds, using a single reed sound and a single-line right-hand melody. When I stopped, there were some different vocalisations and a few smiles from the group, which seemed to reflect humour and anticipation.

Focusing on what we could all do – breathe – was a useful opening to working with this profoundly disabled group of young people. We did this to begin each of our subsequent sessions and it seemed to help to reduce any feelings of anxiety and prepare for music therapy. The use of our breathing patterns and vocal sounds became the main musical theme of this group. Some of the group also responded to the sensory aspects of the accordion; feeling the vibrations through the instrument and touching the different surfaces or playing notes.

Using the accordion percussively

The accordion can be a very tactile instrument, as shown in the case vignettes of Robert and Kieran above. It can also be used percussively. There are many different surfaces to tap, producing different rhythmic effects. The bellows can be played with the fingertips like a guiro, to produce a rasping sound. The bass buttons can be gently tapped to produce various clicking sounds. Although the accordion is not unique in this – the guitar, harp or piano, for example, can also be played percussively – the accordion does have many different types of surfaces to play in this manner. Both Bert Santilly (2009) and Michael Ward-Bergeman (2009) make use of the accordion percussively. I have also used these rhythmic effects successfully to engage children in music therapy.

The Bellows Shake is a musical effect used by accordionists, whereby the player uses his left hand to vibrate the bellows whilst they are only very slightly open, by small rapid rocking movements to and fro with the bass end. This can be particularly useful to imitate train sounds or for sudden dramatic effect. I have used the bellows train sounds particularly in my sessions with one young boy, with autistic spectrum disorder, for whom the theme of trains was both important and interesting. This accordion effect, along with my vocalising, seemed to motivate and help him to feel secure enough in sessions to begin to participate in musical interactions and eventually to move on to other themes and musical ideas.

My first encounter with the accordion

Susan Greenhalgh

I grew up in the Dockland area of Liverpool, and as a young child I was frequently taken by my mother, father and sisters to evangelical open-air meetings held in the streets where I lived. It was here that I clearly remember the piano accordion being played and it being (as well as the preacher!) the star of the show. The piano accordionist would robustly, energetically and with colossal volume, lead the singing of the hymns and without a doubt required no electronic amplification. These visits to the open-air meetings are indeed happy memories for me.

I trained as a music therapist some years ago and my principal instrument is the piano. I also use the violin, guitar and a variety of other instruments in my therapy work, which is mainly based in schools and mental health settings.

A few years ago and in total contrast to the musical quality (and volume) of the accordionist at the evangelical meetings of my childhood, I was to discover the beautiful and more sensitive aspect of the accordion when I heard a colleague play some lovely French tunes. This became my inspiration to start playing the accordion, and subsequently I began using it in school assemblies, in bands I belong to, and eventually in my mental health groups and individual casework. Although a relatively new instrument for me, the amalgamation of my own positive emotional experiences with the piano accordion was what led me to being able to use it in my work. The following case vignette demonstrates how an instrument that provided me as a music therapist with new, positive and happy experiences could also be shared with my clients to generate interest and emotional well-being for them.

Case vignette: Joshua explores dismantling and putting back together before finding the accordion and ultimately, himself

Susan Greenhalgh

I worked with Joshua in his school. At the time of referral to music therapy he was 14 years old. He had recently been taken into care and separated from his three younger siblings, who were still living with their mother. Joshua had become extremely withdrawn, his behaviour was disruptive in the classroom and he was often isolated in school. He found it difficult to concentrate on any given task and was finding it unbearable to remain in any school lessons. It was felt that he might benefit from music therapy intervention, where he might learn to trust another adult and begin to express some of his feelings of loss and anger within a safe and contained space.

Joshua began attending music therapy on a weekly basis. Initially he found it difficult to come into the therapy room and he would often stay outside the door for at least ten minutes. As time went on, he seemed to feel a little more confident, and slowly he began to explore some of the instruments in the room. It became immensely apparent that Joshua was interested in how the instruments worked. He began to dismantle the hi-hat and to question and investigate how the violin and guitar strings are attached and how the sounds are created. He also began to delight in plugging in the electric violin and guitar and seeing how loud he could set the volume. He was developing the ability to ask me questions about the instruments in the room. However, it was still difficult for him to stay focused on an instrument for more than a couple of minutes without becoming anxious and looking sad.

During these first three months of therapy it was brought to my attention that the one school lesson that Joshua would occasionally find motivating was design and technology, where he would be able to learn how to dismantle objects to see how they worked and learn how to put them back together again. His fascination with both the tactile and constructional element of objects had also become very apparent in his music therapy sessions. In addition, I had noted his attraction to varying gradations of dynamics. However, although these seemed to be the two things that did motivate and engage him, it was still very obvious that he struggled to stay focused, even on something he liked. Joshua had still not found something in the room that would capture his interest long enough to enable him to feel settled.

It was at this point that, after much consideration, I decided to introduce the piano accordion into Joshua’s session. This would be something very different from the instruments in the room already. Would the aesthetic quality of the accordion, its tactile and varying dynamic elements, capture his attention? Would the instrument enable him to feel safer and be the means of developing an increased sense of trust with the therapist?

It was Joshua’s 13th music therapy session. He entered the room, immediately spotted the accordion sitting proudly on the floor and smiled at me as I had never seen him do before, an expression I will not forget. It was joyous to see how just the mere sight of the accordion had captured his immediate attention.

Joshua immediately lifted the accordion off the floor and began to try to work out how to produce the sound. He asked how to put on the straps and could not get it on quickly enough. He became totally absorbed in experimenting with the keys and the buttons and soon learnt that the bellows were the heart and soul of the instrument and its main means of expression.

Over the coming months in therapy Joshua began to express some of his intense sadness in the course of his accordion playing; he played long bass drone sounds and I would support him musically with similar sounds on the lower register notes of the piano. When we were engaged in this type of sustained playing, Joshua would become so absorbed and calm that he was able to start verbally to articulate some of his sad and lonely feelings in between our improvisations. Joshua began to sustain his concentration for longer periods during his accordion playing, and what became very apparent was that his anxiety began to decrease during our shared musical improvisation.

His music was still reflecting his intense feelings of being lost and sad, but very quickly he began to discover how to express some of his more positive feelings on the accordion. He had initially been unable to feel positive about anything in his life, but occasionally he was demonstrating a small spark of happiness through his accordion playing.

For the subsequent two months in therapy, Joshua continued to use the piano accordion as his stabilising object in our sessions. Initially, it was the only instrument he chose to play, until eventually he became strong enough to start using some of the other instruments too.

Joshua attended music therapy for three years. The piano accordion had become the turning point in music therapy that had enabled him to take huge steps forward and start to feel better about himself.. He started attending some of his school lessons again, gradually stopped blaming himself for what had happened to him and began to like himself again. He started to make friends with his peers and he became less isolated and more able to cope with some of his difficult feelings.

Social and cultural aspects of the accordion

Dawn Loombe

The unique timbre of the accordion and its history has some cultural connotations in many countries and communities and can have particular resonance with certain social groups. The relevance of accordion music in a variety of communities could be considered socially and culturally important music, described as ‘community music therapy’ (Ansdell 2002; Pavlicevic and Ansdell 2004; Ruud 2004).

Harriet Powell (2009) has described her use of the piano accordion in multi-cultural groups in Hackney, encompassing older people from Italy, Poland and Latvia and from diverse social and cultural backgrounds. Powell has also noted that the accordion often evokes memories of happy social occasions:

Many would not have been able to afford a piano in their home and might have an accordion instead. It was a familiar sound in pubs and at parties and people I work with often relate memories of accordions being played on trips to the seaside or in large community gatherings. (Powell 2004a)

The accordion is useful in playing Jewish Klezmer music and also in providing an easy, effective accompaniment to Middle-Eastern as well as Eastern European music. Santilly (2009) described the use of different scales on the accordion to produce an Asian or Middle-Eastern effect, which has been important in his work.

With relevance to music therapy work, older people who are now in their 70s, 80s and 90s will undoubtedly remember the piano accordion in its heyday. In my work with groups of people with dementia, the accordion has often proved a valuable reminiscence object as group members recall their dance band days and beloved family members who used to play the accordion for social functions. They consistently tell stories of a treasured old accordion in an attic somewhere.

Accordion characteristics in music therapy practice

Portability and adaptability to different therapeutic environments

The ability to play in close proximity to clients in different situations was specifically noted by all of the accordionists. All stressed its suitability for use in hospitals, schools and residential homes, or outside, where they could play wherever the person was, rather than where the instrument was situated. The importance of the client being able to both see and hear the accordion from wherever they were was described by all the therapists, who mentioned that playing accordion allowed interaction visually and through facial expression, which is of course particularly important with those who had lost the ability to communicate verbally. Bert Santilly (2009) explained how he has played his accordion in a special school whilst lying on his back on a mattress beside a child having physiotherapy.

Dawn Loombe found her accordion useful in a children’s nursery, where space was limited. It has also been valuable in circle games involving movement, where the accordionist could dance and physically be a part of the group, rather than remotely playing the piano. In dementia groups, the accordionist can walk around the room playing, which seems to hold the group together, whilst also being able to move to support an individual who is singing or playing a solo.

Use of the accordion bellows to breathe

The accordion is unique in its bellows arrangement. All of the therapists noted the likeness of the accordion bellows to human lungs and to breathing. The accordion’s air valve can be used effectively to produce breathing and sighing sounds without using the reeds.

The accordion’s ability to be shared

Harriet Powell and Dawn Loombe both described sharing the playing of an accordion in their work. The therapist wears and retains overall control of the instrument, whilst allowing the melody to be played by a client on its keyboard.

The changing aspect of the accordion

The accordion is unique in the way that it changes shape as it is played. Different colours are revealed as the bellows open and close. Also, when a long note or chord is played on the accordion, the bellows expand or contract accordingly, meaning that it is represented visually as well as audibly.

Percussive effects

The accordion has many different surfaces to tap, producing a variety of rhythmic effects – its hard casing to use as a drum, buttons couplers and keys to tap or click, and bellows to use as a guiro.

Vibration

Santilly (2009) and Claus Bang (2006) both mentioned the importance of the accordion in their work with deaf and hearing-impaired children, where the children could touch or hold the outer casing of the instrument as the therapist played, enabling them to feel the music.

The attraction of mechanical aspects – buttons, keys, couplers and bellows

As noted in the case vignettes of Dawn Loombe and Susan Greenhalgh, children have been particularly interested in the mechanics of the accordion; especially children with autistic spectrum disorder, who seem drawn to its geometric shapes, buttons and couplers and the way it is constructed.

The dynamic range of the accordion

The use of the accordion couplers allows the player a wide pitch range and also a range of timbres. The use of the bellows for dynamics and musical expression was also mentioned, allowing the player to vary the volume of a single note or a chord whilst sustaining it, or even to have a series of peaks. (Also, the accordionist can sing at the same time as playing the instrument.)

A complete harmonic instrument

Bert Santilly (2009) called the accordion ‘an orchestra in a box’. It is capable of providing a full, strong, harmonic accompaniment. All of the accordionists remarked on the fact that the accordion provides the therapist with a variety of musical options: a single-line melody with or without a chordal accompaniment, as well as being polyphonic.

Social and cultural aspects

The accordion is a popular instrument in many cultures and social groups and has associations with certain styles of music, which might have particular relevance with clients in music therapy. Also, the accordion can be a useful reminiscence object with older people in music therapy. The increased use of the accordion in TV and film soundtracks and in pop culture was also mentioned as relevant.

References

Aldridge, D. (ed.) (2000) Music Therapy in Dementia Care. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Aldridge, D. (ed.) (2005) Music Therapy and Neurological Rehabilitation.. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Alvin, J. and Warwick, A. (1978) Music Therapy for the Autistic Child (2nd edition, reprinted 1994). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ansdell, G. (2002) ‘Community music therapy and the winds of change.’ Voices: A World Forum for Music Therapy 2, 2.. Retrieved 5 April 2009 from https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/83/65.

Bang, C. (2006) A World of Sound and Music. Retrieved 11 April 2014 from www.clausbang.com.

Bright, R. (1997) Wholeness in Later Life. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bright, R. (2002) Supportive Eclectic Music Therapy for Grief and Loss. St. Louis, MO: MMB.

Bright, R. (2006) ‘Significant music in externalising grief in coping with change: The supportive role of the music therapist.’ Australian Journal of Music Therapy 17, 64–72.

Bright, R. (2007) Thoughts on Music Therapy. Retrieved 11 April 2012 from www.fightdementia.org.au/common/files/NAT/20050500_Nat_CON_BrightMusicTherapy.pdf.

Bright, R. (2008) ‘Editorial.’ Creative Expression, Communication and Dementia Newsletter, 2 (March), p.3. Retrieved 24 August 2014 from http://cecd-society.org/assets-australia/Hilary_Newsletter_mar_08.pdf.

Gaertner, M. (1999) ‘The Sound of Music in the Dimming, Anguished World of Alzheimer’s Disease.’ In T. Wigram and J. De Backer (eds) Clinical Applications of Music Therapy in Psychiatry. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Howard, R. (2005) An A to Z of the Accordion and Related Instruments, Volume 2. Stockport: Robaccord Publications.

Loombe, D. (2009) The Use of Piano Accordion in Music Therapy: A Qualitative Study and Critical Analysis of My Own Case Work. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge.

Pavlicevic, M. and Ansdell, G. (eds) (2004) Community Music Therapy.. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Powell, H. (2004a) ‘Light on my feet – the Accordion.’ Musicing: The Newsletter of Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapists, December 2004. Retrieved 11 April 2014 from http://steinhardt.nyu.edu/music.olde/file_uploads/Musicing_2004.pdf.

Powell, H. (2004b) ‘A Dream Wedding: From Community Music to Music Therapy with a Community.’ In M. Pavlicevic and G. Ansdell (eds) Community Music Therapy. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Powell, H. (2009) Personal communication, February 25, 2009.

Ruud, E. (2004) ‘Foreword.’ In M. Pavlicevic, and G. Ansdell (eds) Community Music Therapy. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Santilly, B. (2009) Personal communication, February 17, 2009.

Wade-Matthews, M. and Thompson, W. (2002) The Encyclopedia of Music: Instruments of the Orchestra and the Great Composers. New York, NY: Anness Publishing.

Ward-Bergeman, M. (2009) Personal communication, February 17, 2009.

1See for example, Accordions Worldwide at www.accordionlinks.com.