Читать книгу Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? - Jo Tomlinson - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Amelia Oldfield

In 1978 and 1979, when I was looking into the possibility of training as a music therapist, I was fortunate enough to observe some clinical work with a music therapist who was a first-study oboist. She was working with a ten-year-old girl with severe learning disabilities and autism. She played her oboe and the girl was transfixed by the beautiful sound of the instrument, following the therapist around the room and showing great interest in the instrument and the player. This was remarkable because the girl was usually very passive, disengaged and oblivious to people around her. I knew then that I wanted to learn to improvise and play the clarinet in this way and share my passion and love for the sound of my instrument with others, using my playing to attempt to engage or help in some way.

In 1979, I applied to do a one-year postgraduate music therapy training course in the UK. At that time there were only two possible places to train in the UK, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and the Nordoff-Robbins course. When I was lucky enough to be offered places on both courses, I tried to find out as much as I could about them both, but in the end the decision was easy. If I went to the Nordoff-Robbins course, I would be exclusively focusing on the use of the piano, whereas on the Guildhall course I would be able to develop the use of the clarinet in my clinical work, as well as the piano. As an enthusiastic and dedicated clarinettist, the Guildhall had to be the place for me.

During my training I was never actually taught clinical improvisation skills on the clarinet, although I remember classes where I struggled to improve my keyboard improvisation. However, the head of the course, Juliette Alvin, was a professional cellist and often described case studies where she played the cello. On my placements with music therapists who had all been trained by Juliette, I observed two music therapists who played the violin. Students on the course were encouraged to present case material from their placements where they used their first-study instruments. This was enough to give me the confidence to continue using my clarinet in my clinical practice. However, I was surprised by how few of my colleagues at that time continued to regularly use their first-study orchestral instruments in their work.

In 2015, 35 years later, there are now eight music therapy training courses in the UK. All music therapy students remain proficient musicians, but they will be experts on different instruments. The courses vary in their approaches; the majority emphasise keyboard skills, some will teach guitar accompanying techniques and most encourage students to develop the use of their voice. In recent years there has been a greater emphasis on encouraging music therapy students to develop clinical improvisation skills on their first-study instrument, whether this is a violin, a trumpet or a double bass, for example, or a less well-known instrument such as steel pans, the hang or the Chinese erhu. As a result most music therapy students will now continue to play their first-study instrument and use it at least some of the time in their clinical practice.

As a lecturer on the Anglia Ruskin MA music therapy training course in Cambridge, I teach single-line improvisation, encouraging students to discover their own specific strengths and weaknesses when improvising on their single-line instrument, and exploring with them how each different instrument may be used in a wide range of clinical settings. In recent years many students have become quite passionate about using their own instrument in their work and have chosen, in their second year, to write their MA dissertation specifically about the particular use of that instrument in music therapy. Recent MAs have described the use of the accordion (Loombe 2009), the use of the violin (Roe 2011), the use of the harp (Lo 2011), the use of steel pans (Glynn 2011), the use of the erhu (Tsui 2011) and the use of the hang (Fever 2012).

Given that all the music therapy training courses in the UK have for some years now been actively encouraging students to develop their clinical improvisation skills on all the instruments they are proficient at, it is surprising how little literature there is on the use of orchestral instruments in music therapy clinical work. One of the few people who did write about this was Juliette Alvin, who set up the music therapy training course at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in 1968. She mentions the use of her cello in several case studies (Alvin 1966).

More recently, Salkeld writes about using her clarinet (2008, p.151) and Haire and Oldfield (2009) refer to the use of the violin. However, very few authors actually reflect on the use of their instrument in music therapy, rather than mentioning the instrument in passing as part of a case study. McTier (2012) gives several examples of how he played the double bass when working with young people with autistic spectrum disorder. He writes that ‘the double bass seems to provide a rhythmic and harmonic framework…which is subtly transparent and hence not overbearing’. In my book Interactive Music Therapy, a Positive Approach, I explore the different ways in which I use the clarinet in my work (Oldfield 2006, pp.33–35). In her MA thesis Loombe (2009) examines the literature of two other accordion-playing music therapists, Bright (1993) and Powell (2004), who have written in some detail about how they use the instrument in their clinical work.

These examples in the literature are relatively rare. In the recent collection of 34 case studies edited by Meadows (2011) there is no mention of orchestral instruments. Many case studies describe various uses of the voice and a number talk about using the piano. The guitar is also used, but mainly as an accompaniment to the voice, although Carpente (2011) does mention using the guitar to improvise. Drums and other percussion instruments are often mentioned, and there is a description by Fouche and Torrance (2011) of a marimba group, which is led by a community musician rather than a music therapist. Erkkilä (2011, p.207) describes a case where he taught an adolescent girl some easy bass lines to songs on the bass guitar. However, the bass guitar was mainly played by the client, although the therapist must have had some knowledge of and ability on the instrument in order to facilitate the work. It is interesting that the only two cases that mention the use of instruments other than the piano, the guitar and general percussion, or the voice, are cases where the clients learnt to play the instruments rather than the therapist using the instrument to interact or communicate with the clients in some way. One explanation could be that some of these authors may play and use single-line instruments in their work, but don’t happen to use the instrument in the case they are writing about in this book. In Chapter 5, for example, I describe a case in child and family psychiatry where I used the piano, my voice, the guitar and percussion, but not my first study, the clarinet (Oldfield 2011). So perhaps instruments such as the piano and the voice are used more frequently in our work and this is one reason the other instruments are not so frequently mentioned.

Elsewhere in the literature, many music therapists describe case studies where they use the piano, percussion, or the voice sometimes supported by guitar playing (Bunt and Hoskyns 2002; Darnley-Smith and Patey 2003; Nordoff and Robbins 1971, 2007; Oldfield and Flower 2008; Tomlinson, Derrington and Oldfield 2012). Orchestral instruments, however, are only rarely referred to.

So, there is a gap between the teaching on UK music therapy training courses that accept and train students whose first-study instrument could be any orchestral instrument, the clinical practice where a wide range of instruments are being used, and the existing literature regarding these instruments in music therapy. This book attempts to bridge that gap.

Clients will have a different experience if they are faced with a violin, a tuba or a concert harp, for example. Some music therapists may use their instrument in all sessions, others may only use it with specific clients, or at specific times. Improvisation will be slightly different on each instrument, depending on the tessitura, tone colour and harmonic possibilities. In this book the three editors seek to address these issues by asking practising music therapists to write about their experience of using their first instrument in music therapy sessions. Authors reflect on their own relationship with their instrument, their own love of the instrument, the different ways they use it and what they see as the advantages and disadvantages of that instrument in music therapy. Authors have chosen to write in different ways and some chapters have emphasised some aspects more than others. The editors have chosen to maintain this diversity rather than attempt to standardise the structure of each chapter. Nevertheless, each of the chapters starts with an overview of the instrument itself (which varies in length and detail), includes a number of case vignettes and concludes with a section outlining the characteristics of the instrument in clinical music therapy practice. All the authors have obtained permission from clients to write about the work and publish photographs. Names and details have been changed to maintain confidentiality.

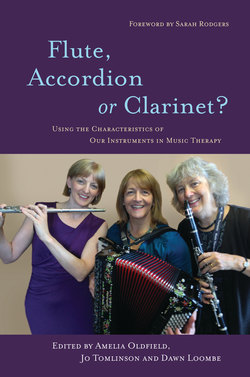

Over 50 music therapists have written for this book. Nearly all the contributors have written about their first instrument, although a few, such as Tomlinson (flute) and Derrington (trumpet), write about instruments they do not consider to be the one they are most expert at, and a few music therapists are equally proficient on several instruments. Most of the authors are from the UK but there are also authors from the USA, Italy, Slovenia, Cyprus and Norway. When looking for contributions the editors found it relatively easy to locate music therapists using popular instruments such as the violin, the flute and the clarinet. It was harder to find double bass players and brass players and the editors were not able to find French horn playing music therapists, although, in the concluding chapter, when I write about training music therapy students, I have included a letter that one of the students wrote to her French horn. I am very grateful to Caroline Swinburne for allowing me to publish this letter and pleased to report that she has now been practising as a music therapist for over a year, and regularly uses her French horn in her work.

The editors decided to include all orchestral instruments as well as harp and guitar. We also included the accordion because this instrument is used by a number of music therapists but has not been written about very much in the past. However, we did not include percussion, keyboard or voice as these instruments have been written about more extensively in the music therapy literature. The same could be said about the guitar, but we felt that most of the literature mentions the use of the guitar as an accompanying instrument rather than as a melodic instrument, so it was worth including a chapter exploring the use of the guitar in its own right. Because of the problems of space it was decided not to include the steel pans, the hang, or instruments from other countries such as the Indonesian Gamelan, the Chinese harp or the erhu. Perhaps a future book could be devoted to the use of these instruments in music therapy.

Since the emphasis in this book is on the use of the music therapist’s own instrument in clinical settings, the work described here is all improvisational music therapy where live music is created by the therapist to engage, support or aid the client in some way. The use of recordings of different instruments in music therapy, or of other receptive music therapy methods, has not been documented in this book. Again this might be a topic for a future publication.

In each of the chapters, the editors have tried to ensure that case studies in different clinical areas have been included, such as work with children and adolescents, adults with learning disabilities, adult psychiatry and work with the elderly.

The use of the voice, the piano and percussion has been explored and written about in the music therapy literature. However, no previous book has examined how therapists use other specific instruments. This book will be of interest to music therapists, student music therapists, music therapy educators and anyone interested in music therapy, including healthcare professionals, teachers and parents. More generally, it will be relevant to those who are intrigued by the unique qualities of particular musical instruments.

References

Alvin, J. (1966) Music Therapy. London, UK: Stainer and Bell.

Bright, R. (1993) ‘Cultural Aspects of Music in Therapy.’ In M. Heal and T. Wigram (eds) Music Therapy in Health and Education. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Bunt, L., and Hoskyns, S. (2002) The Handbook of Music Therapy. Hove, UK: Brunner-Routledge.

Carpente, J. (2011) ‘Addressing Core Features of Autism: Integrating Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy within the Developmental Individual Difference.’ In T. Meadows (ed.) Developments in Music Therapy Practice: Case Examples. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Darnley-Smith, R. and Patey, H. (2003) Music Therapy. London, UK: Sage.

Erkkilä, J. (2011) ‘Punker, Bass Girls and Dingo-man: Perspectives on Adolescents’ Music Therapy.’ In T. Meadows (ed.) Developments in Music Therapy Practice: Case Examples. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Fever, J. (2012) The Use of the Hang in Music Therapy. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.

Fouche, S. and Torrance, K. (2011) ‘Crossing the Divide: Exploring Identities within Communities Fragmented by Gang Violence.’ In T. Meadows (ed.) Developments in Music Therapy Practice: Case Examples. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Glynn, J. (2011) An Exploration of the Steel-pan in Music Therapy. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.

Haire, N. and Oldfield, A. (2009) ‘Adding humour to the music therapist’s tool-kit: Reflections on its role in child psychiatry.’ British Journal of Music Therapy 23, 1, 27–34.

Lo, F.S.Y. (2011) The Use of the Harp in Music Therapy. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.

Loombe, D. (2009) The Use of Piano Accordion in Music Therapy: A Qualitative Study and Critical Analysis of My Own Case Work. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.

McTier, I. (2012) ‘Music Therapy in a Special School for Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder, Focusing Particularly on the Use of the Double Bass.’ In J. Tomlinson, P. Derrington and A. Oldfield (eds) Music Therapy in Schools: Working with Children of All Ages in Mainstream and Special Education. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Meadows, T. (ed.) (2011) Developments in Music Therapy Practice: Case Examples. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Nordoff, P. and Robbins, C. (1971) Therapy in Music for Handicapped Children. London, UK: Victor Gollancz.

Nordoff, P. and Robbins, C. (2007) Creative Music Therapy: A Guide to Fostering Clinical Musicianship (2nd edition). Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Oldfield, A. (2006) Interactive Music Therapy, A Positive Approach: Music Therapy at a Child Development Centre. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Oldfield, A. (2011) ‘Exploring Issues of Control through Interactive Improvised Music Making.’ In T. Meadows (ed.) Developments in Music Therapy Practice: Case Examples. Gilsum, NH: Barcelona Publishers.

Oldfield, A. and Flower, C. (eds) (2008) Music Therapy with Children and Their Families.. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Powell, H. (2004) ‘A Dream Wedding: From Community Music to Music Therapy with a Community.’ In M. Pavlicevic and G. Ansdell (eds) Community Music Therapy.. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Roe, N. (2011) An Exploration of the Use of the Therapist’s First Instrument: The Experience of Interaction and Emotion in Music Therapy Focussing upon the Violin. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.

Salkeld, C. (2008) ‘Music Therapy after Adoption: The Role of Family Therapy in Developing Secure Attachments in Adopted Children.’ In A. Oldfield and C. Flower (eds) Music Therapy with Children and Their Families. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Tomlinson, J., Derrington, P. and Oldfield, A. (2012) Music Therapy in Schools: Working with Children of all Ages in Mainstream and Special Education. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Tsui, L. (2011) The Use of Erhu in Music Therapy. Unpublished MA thesis, Anglia Ruskin University.