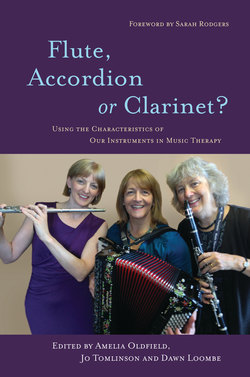

Читать книгу Flute, Accordion or Clarinet? - Jo Tomlinson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

The Flute

Contributors: Caroline Anderson, Veronica Austin

(introduction and case vignettes), Emily Corke,

Mary-Clare Fearn (within Veronica Austin’s

contribution), Esther Mitchell and Jo Tomlinson

Introduction

The flute is the oldest of all instruments that produce pitched sounds, and its evocative tones have been associated with healing and lifting the spirits from before the Middle Ages. The scientific journal ScienceDaily reported the discovery of what is thought to be the oldest flute, made from bird bones and mammoth ivory with two holes in it, and approximately 40,000 years old (University of Oxford 2012). Although no one can be sure of the precise function of these flutes it is generally thought they would have been used for rituals, ceremonies, pleasure and perhaps, even then, for healing.

When taking into account the history of the flute worldwide, we find there are many versions of primitive flutes and their flute families remaining in the sounds, music and traditions of different world cultures and healing practices today. It is worth considering that some of the ideas raised in the use of the orchestral flute in music therapy are applicable to the use of these other types of flute, such as the Irish tin whistle, the panpipes of Ecuador and Peru, the Japanese shakuhachi, the Indian bansuri flutes, the Indonesian suling, the Chinese bamboo flute or the wooden dual-chamber North American flute (one side plays a drone and the other pitched notes). There is much to inform and draw on from these world flutes for the benefit of music therapists. In order to appreciate the modern orchestral flute it is useful to understand a little of its history.

The primitive flutes of hollowed-out bone or horn and later clay, bamboo or wood of the medieval and Renaissance periods were a one-piece design with up to six holes and a mouthpiece. They were either played straight down, using a block to direct the air at the edge of the mouth hole (like the recorder), or played to one side (transverse), requiring the player to direct the air across the mouthpiece. Fingers covered and uncovered the holes to create different pitches. Intervals of the pentatonic scale and later diatonic scale of one and then two octaves evolved.

The quality of timbre, expansion of pitch range and capacity for the flute to convey expression developed over time as flautists increased their skills, composers wrote more complex music, and technology advanced. The second half of the 17th century saw a revolution in flute making (Wilson 2013) with the new flexibility of the three-piece transverse flute (mouthpiece, centre and foot piece) of the Baroque era, with its three-octave range, brighter tone and ability to effect more dynamic contrast. The one-keyed flute was developed into the six-keyed flute in the latter half of the 17th century and the tone became more even. Mozart’s Flute and Harp Concerto of 1778 was intended for such a flute. Throughout the 19th century the flute continued to undergo more changes, evolving to the modern Boehm system metal flute predominantly in use today.

Figure 3.1 Range of the modern concert flute

The wider implementation of instrumental lessons in schools, as well as the internationally acclaimed flute virtuoso James Galway (b.1939) did much to popularise the flute in the 1970s and 1980s. Galway’s flute version of John Denver’s ‘Annie’s Song’ in 1978 reached number three in the UK pop charts, and a surge of new young flautists followed. He became a household name and is still successful today as a cross-over artist, bringing classical, folk and popular music to different generations of flute players and a diverse range of music lovers. New careers in flute playing have expanded to provide opportunities for flautists to work as therapists, performers, teachers, composers, recording artists and flute specialists in manufacture and industry. Among music therapists the flute is the orchestral instrumental most frequently used.

Of course invention has not stopped, and since the advent of the 21st century, developments of the quarter-tone flute by Robert Dick and Eva Kingma2 have been established in a new kind of flute called the Kingma System flute. With the help of additional keywork, players no longer have to use alternative fingerings for correcting intonation, playing trills or effecting extended or contemporary techniques, as they are sometimes called (Clarke 2012; Dick 1986). Players at all levels are now becoming acquainted with extended techniques. Clarke (2012) described this development: ‘They are becoming a natural augmentation of core technique both with respect to the requirements of new repertoire and learning approaches.’

Many techniques are still possible on the ordinary concert flute, though the open-holed flute with a low B footjoint is favoured. Techniques include the development of new tonal colours and sonorities as well as note bending, jet whistles, harmonics, flutter tonguing, percussive articulations (mouthsounds), multiphonics and quarter tones.

Music therapists will be able to expand their range of available responses to their clients by employing some of these additional methods on their flute. In imitating sounds of the early flutes using non-standard fingerings, therapists might connect with clients by creating more primitive or other-worldly sounds. Special effects with multiphonics and jet whistles may bring surprise and novelty. Singing into the flute and percussive articulation lend themselves to popular or avant-garde styles, where it might be important for the therapist to sound contemporary or even cool! While critics have called these ideas gimmicky and a generation of flute playing therapists may feel challenged by learning new ways of playing, our clients may motivate us to explore these options. When feeling, imagination and technique come together, the therapist is best equipped to use the flute to its full potential.

The flute in music therapy literature

Music therapist Juliette Alvin (1966) wrote about Greek mythology where the flute was ‘Athena’s gift’ from the gods, and went on to describe the attitudes of the Greek philosophers towards the flute and healing. Alvin quotes Aristotle’s opinion that the flute is not an instrument that has a good moral effect – Aristotle considered it ‘too exciting’ and his belief was that it should consequently be employed only on occasion when the object of the music is the purging of the emotions rather than the improvement of the mind.

From a practical perspective Alvin also discusses the positive impact of blowing into flutes for people with malformation of the mouth, and the possibility of developing muscle strength through playing (Alvin 1966).

Music therapists Sweeney-Brown and Wilkinson have written about their work with children in hospices, using the flute to calm, soothe or stimulate children who were approaching the end of life. Wilkinson (2005) observed the range of responses to the flute from a group of children: some listening quietly whilst another vocalised in imitation of the flute sound. Even when children were too unwell to engage with active playing, the sound of the flute provided reassurance and allowed the child to feel that they were not alone. This in turn supports the families of the children and created positive memories during times of severe stress (Sweeney-Brown 2005).

Tomlinson (2012) described the use of the flute in music therapy work with young children in special schools, and the way in which the flute could be used as imitator of the child’s musical contribution. ‘Shaky’ playing on the egg shaker was reflected back by the therapist playing trills on the flute and making similar physical movements to those of the child. The element of humour lightened the intensity of this exchange, engaging the child and creating much less resistance to shared interaction. In a similar way rhythmical imitation on the flute provided a musical framework for the child, encouraging him to sustain interaction and distracting from obsessive or repetitive behaviours. Tomlinson stated that this type of imitative play using the flute can be used ‘to reinforce existing behaviour, or at other times it can be used to promote change…imitation and reflection used within a therapeutic context can be powerful and valuable tools’ (2012, p.115).

Keeping connections through flute playing

Veronica Austin

I was born into a musical family and was drawn to carry on the flute-playing tradition. I loved the sound of the flute and was surrounded by some of the finest flute-playing sounds in England in my formative years. My father, a musician and businessman, and then Richard Taylor took me on as my teachers and mentors. My relationship with the flute is embedded with family memories and relationships, as my sisters, brother and I regularly went to concerts and also played together as a wind quartet. For the past 15 years I have continued to play in a wind quartet but with music therapists, all of us wanting and needing to stay connected to our instruments and finding it musically and socially fulfilling.

On a practical level, the modern orchestral flute is easy to carry around and can be relatively inexpensive to buy. It is easy to care for and to learn as a beginner because it does not involve a reed and the complications that can bring. For anyone who has made a start on the recorder, fingerings can be easily transferred to the flute, and frequently you can enjoy playing the melodic line. The playing posture required allows the music therapist to face the client, and the small size of the instrument means movement around the room is possible. But perhaps it is the particular sound that is first and foremost the flute’s enduring attraction; it is a versatile instrument capable of a wide range of timbres over a three-octave pitch range. The lower octave can be rich, smoky or mellow, while in the higher registers the sound of the flute can be piercing, with bird-like trills and rapidly moving notes. It is possible to play extremely quietly on the flute, and allow the sound to fade away to a whisper of breath, or play around with breathing sounds.

I have noticed that music therapists using their flutes effectively in therapy tend to be at ease with their instrument, as if their instrument is simply an extension of themselves. I experienced a revived connection and confidence with my flute after a period of more intensive flute practice and inspiring flute lessons. In the following clinical example with a group of early-years children in a local authority Sure Start Centre, the flute offered a profound connection with all the children.

Case vignette: Early-years group

A group of four very different four-year-old children, two girls and two boys, were in their sixth music therapy session. They had been referred for music therapy for a variety of reasons, some having difficulties making relationships and one having challenging behaviour. After directing the first five sessions in a mixture of structured and semi-structured activities, I wanted to open up the group play with more free improvisation. The group began exploring percussion sounds as separate individuals, and one child broke off to start dancing. This child was moving in breakdance movements, and in the absence of a keyboard I took up my flute and with this single line using the Dorian mode and an off-beat jazzy kind of rhythm I accompanied him and the other children as they began to join in. The flute sustained a group dance in a most joyous way, which also proved a turning point in the therapy.

In the example above, the flute practice and lesson in the weeks before had helped renew my connection to the flute, which I then transferred to the group in a strong accompaniment. Using the flute here also enabled me to move about with the group and give my own occasional dance-like movements in response too.

Keeping a connection to one’s instrument promotes artistry in music therapy. Artistry sets apart the ordinary player/therapist from the one who is maintaining and honing their skills with workmanship and imagination. For the flute, these involve technical mastery of the fundamentals of flute playing, a rich clear and focused tone, evenness of tone over the range of the instrument, warmth of expression, articulation and dynamic contrasts, control over breathing and vibrato, and the ability to project the sound and rhythms into the clinical space. More advanced or experienced players may have a greater ‘sound palette’ (Clarke 2012) at their disposal, a repertoire of well-known tunes to produce at any given moment in any style or key, and be able to communicate an idea, feeling or thought with conviction. The artiste will add a quality to their sound, the way it is conceived, produced and projected, with nuance and variation in attack, articulation and timing. The artiste has their own authentic style of playing and interpretation that comes from within. However, there is a note of caution from music therapists Sobey and Woodcock (1999, p.138) for the therapist who ‘has brought into the session too much of his own musical and cultural world’; in their case example ‘the client in a purely musical sense was left with no other options than to join this world, go actively against it or to remain passive and silent’. Therapists aware of their tendencies through supervision and listening back to recordings learn to continuously monitor the connection their music is having with their client and how best to employ their music for therapeutic benefit. As music therapist Pavlicevic (1997, p.121) writes: ‘The significance of clinical improvisation is that it is an interpersonal event, rather than only being a musically interactive one.’

The flute as object

The flute, and sometimes its case as well, may be seen as an object in itself carrying significance in the therapy space. When the flautist makes the decision to take their flute into therapy work they do so with care. It is necessary to consider whether the situation can be made safe and practical. Many therapists will have a second, cheaper flute to take into therapy work in order to preserve their other more precious instrument. A therapist can also think through the ways in which the client might potentially respond to this flute in the room today. Will they embrace it, be ambivalent or reject the flute? If they do have any of these responses, we might interpret the feelings as being about us. We might even actually feel rejected or embraced by their attitude as we consider the object we have taken into the room as an extension of ourselves. With some clients, wondering out loud with them about their responses might be possible, and if not, the therapist can still reflect on them.

The gifted cellist and pioneer music therapist Juliette Alvin taught that in her method of music therapy the instrument and the music took the transference feelings from the client (Bruscia 1987), thereby providing psychological safeguarding for the client and therapist. Object-relations thinking also allows us to consider that the therapist, the environment or their instrument may be construed or unconsciously used as a recipient of transference and projections by the client. This can provide information for the therapist and clues to the client’s predicament or feelings.

A young girl on meeting a therapist for the first time had a panic attack on seeing the flute and needed another adult to calm her and the flute to be removed. Because the work was happening in a hospital setting and the young child had had a tracheotomy, the therapist could conjecture that the flute could have been perceived as a medical instrument that might cause her physical pain, or a blowing instrument needing the mouth, causing her psychological pain. Finally, the flute may also be considered as a transitional object (Winnicott 1971) that simultaneously separates and brings together therapist and client, belonging ‘to the border between the child’s early fusion with mother and his dawning realisation of separateness’ (Gomez 1997, p.93).

A wind instrument – connecting with breath and blowing

In flute playing, the breath can be readily seen, heard and emphasised. The fact that this aspect can be brought to the fore in a very natural and appealing way is a significant role for the flute in therapy. Young children with speech and language difficulties and developmentally delayed babies can benefit from attention being drawn to the movement of the mouth and breath. The connections with the body and arousing mental and physical awareness can also be developmentally advantageous. There is stimulation in the feel of the air and children are also captivated by the sound and sight of the flute. I have seen children automatically put beaters to their mouths and hold them sideways in imitation of the therapist, or pucker their lips in a way that mirrors the therapist’s embouchure. To illustrate some of these ways of using the flute here are two examples of clinical work from music therapist Mary-Clare Fearn, whose main instrument is the piano but here finds her flute a very valuable tool as part of the therapeutic process.

Case vignette: Nicholas

When I commenced work with Nicholas, he was eight years old and had learning disabilities with associated emotional and behavioural problems. He was very controlling, often saying ‘Shut-up!’ or ‘Be quiet!’ if I started playing the piano. However, Nicholas did allow me to play the flute and this led to him using the melodica. It was clear that he was motivated to choose the melodica because of his desire to blow into an instrument. Nicholas accepted the boundary that he could not play the therapist’s flute and took ownership of the melodica. He has since used it many times in the past three years, gradually experimenting with different scales, chords and intervals. Each time, his music is beautiful, sonorous and moving. Nicholas has a troubled home life but is very loving and keen to learn; unfortunately his keenness is often hindered by his emotional state. He can get very angry but his music, particularly the flute and melodica duets, seem to tap into the gentle side of his character, which he allows to come to the fore in these moments. Nicholas always makes clear endings using a diminuendo, giving the feeling of a sigh.

Case vignette: Anna

Anna is a profoundly disabled girl who I began to work with in music therapy sessions when she was three years old and this work continued for four years. Anna engaged in music and movement therapy work with an adult facilitating her movements. She was blind and could not move unaided but clearly wanted to get close to the source of the music. Frequent early sessions with Anna’s head resting on the therapist’s crossed legs and moving her flute close to the young girl’s face produced delight when she felt the breath and, with adult facilitation, touched the flute as I played. This felt extremely close. My mirroring of the rhythm of Anna’s breathing added greater security to our relationship. The flute being ‘breathy’ seemed to make the perfect link and helped her to realise that she was dictating the improvisations.

In both of the case studies above, the flute was a far more appropriate instrument of choice than the piano. It was not so intimidating for the children and the sound appealed to them. In addition to this, the flute facilitated the children’s self-expression and I was able to get physically closer, which created a more personal feel to the music-making and enabled a relationship to develop.

The flute as an extension of the voice

The flute can be thought about and used as an extension of the therapist and his or her voice. First, it is possible quickly to take away the flute in the middle of a melody and sing the rest with your voice in a seamless way, providing a continuous melodic line whilst also simultaneously enabling your client to become actively engaged. The following case example used this technique.

Case vignette: Simon

One-year-old Simon was seen for music therapy in a hospital ward and was recovering from an operation to counteract the damage to his lungs from continuous vomiting. He watched transfixed as I put my flute to my mouth and started to play a few notes mid-register. I stopped and then played a few more notes moving up and down scales in a melodic way, watching Simon intensely for signs of response. At first he seemed startled, but then his face softened and he began to move his body to and fro from his steady base in his Bumble chair. He looked up and smiled and I then sang the next phrase. After this, I blew the flute and sang again to Simon’s movements. He increased his movement and engagement with me in this joint activity and when I next blew and then waited, Simon made his own vocal sound in the space. A series of flute and vocal exchanges then took place to both his and his mother’s delight.

In this case, the waiting was as important as the notes. Also, I paid extra attention to Simon’s tempo and timing, wondering whether I had perhaps played too quickly before. Simon almost fooled the doctors by his incredibly sunny disposition, despite vomiting and being in hospital. By looking at his X-rays the doctors discovered that his lungs were badly affected. In a similar way, by slowing down the musical interaction I began to notice Simon’s breathing and aimed for more control and ease for him, by paying attention to his internal movement as well as his external movements.

A second function of the flute acting as an extension of the voice is that it can accompany a vocal line when the client is singing. The combination of the flute and the voice creates an opportunity for a shared experience with the therapist. If the therapist joins in through singing, this will often mean the client drops out and stops singing. By accompanying with the flute we can do the same thing, but we are also different and separate.

The instrument that reached where others could not

Esther Mitchell

At the age of nine, I discovered a small black and silver box in the dining room. It looked remarkably like something I had seen at the doctor’s. Was someone ill? Guiltily, unseen, I opened the lid. Within, however, was not the stethoscope I expected but, in three enticing pieces, my first flute.

Although I studied technique and tone for 14 years through the joy of lessons and chamber music and the struggles of exams and performances, it was not until I came to train as a music therapist that I really connected with my flute. It was through improvisation that it really became a part of me, an extension of my voice through which I could express my emotional state and also increasingly, reflect back that of another.

I have used my flute within clinical work with a wide variety of client groups and have often wondered why it can apparently entice individuals into interaction where other instruments have seemed to fail. My conclusion is that this is due to its similarity with the human voice. My voice is naturally low, and the flute provides me with the higher pitches I lack. With it I can meet a range of vocal sounds produced by those I work with, which test my voice beyond its limits.

I work for Thomas’s Fund, a registered charity that provides music therapy in the home for children and young people with life-limiting conditions and/or disabilities, who, owing to their medical condition, are too unwell to attend school for prolonged periods. Our work is short-term, with clients being offered on average 14 sessions, including assessment. Those referred, from babies up to the age of 19, vary greatly in their physical and mental state. Some clients live a few minutes’ walk away from where I park my car or up several flights of stairs. So our instruments need to be compact, and I have come to respect the choice my parents made – that I should learn the flute, not the harp – as I swing its bag over my shoulder or open the case in the confines of a small cubicle, never ceasing to delight in the wonder on a child’s face as I put the shiny pieces together.

Case vignette: Ben

Ben, aged 20 months, grinned broadly as I began to sing hello to him, softly strumming the guitar. The child, who had been on the move constantly, rolling over and over across the room at our initial meeting, barely aware of me, was sitting attentively on the floor in his living room. His mother sat next to Ben and he was giving me steady eye contact. I inched a little closer and began to sing again. Ben’s face dropped and he began to sob, then to shake with fear. He could not be consoled or distracted whether I sang, played or moved away, leaving instruments near him, which his parents explored with him. After 15 minutes, we ended the session, Ben calming as I packed away and left. Sessions two and three continued in a similar manner with his parents becoming understandably uncertain about music therapy in general. I decided therefore to work without instruments; I would use my voice and props such as puppets and scarves and I hoped would slowly gain his confidence.

Ben has Rubenstein Taybi syndrome, a chromosomal disorder that affects his mental development, his sight and hearing, his digestion, his joints and his growth. Much of Ben’s first traumatic year of life was spent in hospital, and it was hoped that music therapy could support him in the development of his very delayed communication, social and physical skills. Ben made virtually no vocal sounds and gave very little eye contact.

Ben was used to noise from the television, which was on much of the time, and he enjoyed shared play, yet appeared unable to cope with musical interaction. However, I noticed that as I worked with only my voice, he gradually began to let me in. Our sessions were filled with action songs, which were new to his mother, whose first language is not English. She was keen to learn and Ben appeared increasingly motivated, pausing in his relentless activity of rolling to sit for increasing periods and engage. In session six, feeling as if I were treading on egg shells, I tentatively reintroduced instruments. Within weeks Ben moved from tolerating first the tambourine, to exploring and mastering an understanding with delight that his play on the egg shakers could impact on how his mother and I played too.

In session ten I introduced the flute. Ben was exploring the wind-chimes for the first time and seemed quite captivated. As I started to play my flute, mirroring his phrases, he immediately stopped playing, sat forward and watched me intently, giving me a level of attention that I had not felt before. Ben’s mother moved the wind-chimes and turned to watch his face. I continued, tentatively moving higher up in the register to meet his sounds; Ben’s face dropped and he began to sob. I immediately stopped playing, fearing I had taken him back to square one. I wondered if the sound was hurting his ears, or whether this was something much deeper; perhaps too emotionally intense?

Spurred on by his initial response to the flute, I began to use it weekly, introducing it within our interaction with a variety of instruments. Ben would stop what he was doing as I began to play and, now crawling, would approach me as if drawn by some magnetic connection. Our interaction would at that point become more focused, and I noticed from the video that his mother would sit totally still. Ben was now able to turn-take for brief periods, giving more consistent eye contact and enjoying a variety of action songs; he had apparently begun to anticipate phrase endings within our shared play. He was increasingly vocal in and outside sessions, using his voice now as a medium for self-expression, rather than intentional communication, through closed ‘hmmmmm’ sounds.

In our final individual session Ben, his mother and I shared the gathering drum. Ben played with steady beats, yet I felt he was not really interested in communicating. I lifted my flute to play… he sat up, leant forward across the drum and beamed, tilting his head to one side, his eyes suddenly full of life. As I played, responding to his movements through my own, he began to use the drum to turn-take with my sounds. Ben’s mother commented on how much he was listening. Later, adding in the egg shakers, the music became more upbeat, with his mother and me mirroring his play. Ben suddenly began to vocalise, mirroring the pitches and shape of my melodic flute phrase for the first time. Each time he responded to my sounds he launched himself at the drum, trying to kneel up and support his own weight. Our shared dance went on and on, pausing briefly as he toppled over, then back to reinitiate the interaction through a repeated vocal phrase, a big smile and pleading eye contact.

It can be difficult to work within the parameters of short-term music therapy with those who would benefit from something more long term and I was very fortunate to soon see Ben again, now in a small group situation. He continued to develop his confidence, his awareness, his communication and his social and physical skills. Having spent a long time in hospital, then much of his time at home, he was now enjoying being a part of various groups in the community. This was reflected in his interest in the other children in the group, his eagerness to explore the large room each week and his confidence to be the first to reach out to try the instruments, even the guitar, which he could now at last accept. Interaction during the session was naturally more structured and I did not feel the same intensity within interaction as we had had in our individual therapy. However, each time I introduced the flute, he would immediately approach and sit directly in front of me, whether it meant sitting on top of instruments or another child! In our penultimate session, Ben approached me and placed his hands on my legs as we sat together on the floor, and each time I stopped playing he would push the flute back up towards my lips. I laughed, asking and signing ‘Do you want more?’ Ben nodded, smiled and vocalised an affirmative.

From our very tentative beginnings to the end of our time together, Ben had undoubtedly become motivated by the percussive and melodic instruments I offered him each week. Through shared play and turn-taking exchanges, he had shown clear development towards his therapeutic aims and would most likely have done so without the presence of the flute. It was, however, through the use of the flute that I felt Ben and I really met in the music emotionally. It touched him on such a level that his whole being became alive. In that moment we had a shared understanding, our relationship was taken to a deeper level and it was from that level that interaction flowed unconsciously. This intimacy did, I believe, support Ben’s development further, taking us a step beyond where we would have been without the flute.

The calming effect of the flute

Emily Corke

At school, my earliest musical memory is being part of the recorder ensemble, which developed my interest in woodwind instruments. The novelty of breathing into something but making a sound other than one’s voice led me to begin learning the flute, and I discovered its many further qualities. In keeping one’s breath steady one can create musical phrases and melodies with a pleasing soft tone. Its sound is soothing, yet crisp. I was attracted to its delicate and intricate nature, the shiny, striking metal out of which it was made. I went on to play the flute for eight years at school, and was particularly grateful for orchestral opportunities not afforded me through my two other ‘instruments’ of piano and voice. The flute was my gateway to relational music, corporate musical discovery, mutual support and performance. I neglected the flute upon leaving school, but when I started my training as a music therapist I remembered the flute’s communicative possibilities in creating powerful music with others.

I now use my flute in nearly every session, and I delight in seeing my clients drawn to it in the same way that I am. The flute includes a different dynamic in three main ways. First, it is the only instrument that I play but the clients do not, allowing them to enjoy merely listening to and absorbing the sound. Being able to simply listen to the soothing sound allows my clients to feel less pressured to ‘do’, and therefore, counter-intuitively, they seem more at ease to respond. Second, it is seen as a special, delicate instrument, attracting clients to listen intently and gaining their attention for prolonged times. Finally, its portability allows me to move around with it easily and remain free to both play and physically mirror my clients’ responses.

Figure 3.2 The engaging effect of the flute

Case vignette: James

James, a 13-year-old boy with autism, was referred to me because of his hyperactive tendencies, and he attended 17 sessions of music therapy. What first struck me about James was how young he looked for his age, and how he spoke and sang in a childlike voice. As we began, James’s love for music swiftly drew him into interaction with me, and he would be quick to respond. Before the sessions he would enter the room already singing our greeting song. However, his eagerness to play and sing caused him to rapidly become over-stimulated and overwhelmed, especially during familiar songs. Our interactions would quickly break down and fragment. His singing would become jumbled and slurred; he would become erratic, shout and squeal, play instruments deafeningly loudly and exhibit fixated movements. These expressions, along with his childlike voice, gave me a window into his feelings – muddled, ‘unable’ and lacking control. In fact, in the beginning phase of therapy James could only play at one volume and in one style: extremely loudly and chaotically.

Singing, especially of familiar songs, seemed to be what James enjoyed the most, probably owing to the safety it provided through structural form; yet it made him the most overwhelmed. As he became over-stimulated, I would stop using my voice and pick up the flute, responding with uncomplicated and grounding music until he calmed down. I also found that when we sang and played without lyrics, or played improvised melodies, he was able to express himself more freely. Sometimes I would hum the melody lines, which he would respond well to, but as the sessions went on, I found the flute much more effective at keeping him calm yet also interactive and expressive.

As I reviewed my video footage from the sessions, I noticed that when I played the flute James would frequently be looking out of the window in between playing. Outside there were big leafy trees, softly swaying around in the breeze. I noticed the connection between the gentle and calming nature of the flute and the way the trees moved. It seemed James had made a connection between what he could see and what he could hear, and in connecting these stimuli he was led to express himself in a more controlled manner. In these interactions James would usually choose to play the glockenspiel, a delicate instrument, mirroring the characteristics of my own music, and of the trees, and he would play it gently and sensitively. I felt that I was acting as the mouthpiece for our soothing sounds and landscape. Our interactions would usually sound conversational as we took turns to answer one another in our playing, and our motifs would be slow and reflective. By playing the flute we could bypass James’s anxiety of using his voice, but retain a distinct melodic line. It acted as a voice, detached from ours, but allowed a form of expression still generated by breath, yet controlled and relaxed. I was modelling an alternative, soothing ‘voice’, which was mirrored by his own ‘voice’ on the glockenspiel. As these interactions kept occurring I slowly integrated my contribution, alternating between singing and flute. I would sing or hum in a similar pitch and gentle tone, mimicking the flute. My use of voice was not enough to overwhelm James, and so he would respond as if I was playing rather than singing. Gradually James started to use his voice too, sometimes in a shouty manner, but without escalating out of control as it once would have done. He went on to explore and develop a quieter voice over time.

In our penultimate sessions, James would still enter singing our greeting song, but with one significant difference; he sang in a softer tone and with more coherence. As I watched the video back and observed us singing ‘Hello’ together for the last time, I realised how much control James had gained over his vocalisations and other expressions. In our ‘Hello’ song James now sang a verse on his own as I accompanied him on the guitar, which had become the normal way for us to start. I realised that a reversal of roles had occurred. I didn’t always need to be James’s voice for him; he could now sing in a moderate and controlled manner, echoing the voice of the flute and glockenspiel, and mirroring the landscape he saw outside.

Vittorio and the magic flute

Caroline Anderson

I began learning the flute in primary school and played in various ensembles, and then went on to take a music degree with major performance on flute. After completing my degree I worked as a peripatetic woodwind teacher and conductor for several years, continuing with lessons and ensemble playing in my own time. We were encouraged to use our first-study instruments in classes and on placements on the music therapy training course. In fact, one of our first assignments was to write a letter to our first instrument, and this task reminded me of how familiar I am with this instrument, the hours I have spent practising, all the exams, concerts and recitals I have poured my energy and emotions into. As I have greater proficiency on the flute than on other instruments, I feel I can respond more effectively and have a wider musical range at my fingertips, while requiring less effort, so focusing more of my concentration on the client.