Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

Mom, Dad, and Me

In their own way, by their own lights, they tried to care for you tried to teach you to care for objects of their caring.

— Adrienne Rich, “Meditations for a Savage Child,” from Diving into the Wreck

I wasn’t a total angel. My first conscious act of disobedience occurred when I was four. On the weekends my father would take me sledding down the gentle slopes beside Balmy Beach Canoe Club. Some other children would go down the hill sitting backwards on their sleighs.

“Daddy, I want to go that way down the hill.”

“No, Lorraine. You’ll hurt yourself if you do.”

Ignoring his warning, I went down — backwards. It was an uneventful ride. No bumps or collisions. Yet as I trudged up to the top of the hill, I felt blood running out of my nose. Where had the nosebleed come from? Is that what happened when you disobeyed? The mysterious power of parental prohibition was indelibly impressed on my mind.

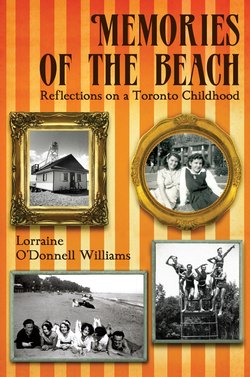

Balmy Beach Canoe Club as it looked in the 1930s. Beacher and Canada Sports Hall of Fame athlete and sports writer Ted Reeve stands in back row, second from left.

Those outings with my father were special because he was away all week. Life normally had a regular routine, although one night in July 1936 that routine was altered. Small changes have a huge impact on childish minds. My parents took me down to the hill above the Balmy Beach Canoe Club and said we were going to sleep outside that night. This, to me, was a grand adventure. Their reasons were practical and necessary however. The temperature had soared to 105 degrees Fahrenheit (almost 41 degrees Celsius). It was the worst heat wave in Canadian history. My mother was pregnant with my sister Suzanne and my father knew we had to get out of our hot basement apartment. So we slept out under the stars surrounded by scores of other Beachers. With no air conditioning available then, 542 Ontarians eventually died. Our proximity to the waters of Lake Ontario saved us.

The baby carriage was always placed outside our basement apartment window. That way, if the baby cried, my parents could hear it.

One of Dad’s letters from 1941 when he was still on the road. He’d get only a small commission on the $110 dollar order!

Most of my time was spent with my mother. Thursday was a special day in my week. Mom and I would sit at the kitchen table in our basement apartment. There’d be an accumulation of letters my dad had sent her that week. She’d read each one aloud in sequence. When she’d finished, I’d join her in the ending I knew by heart. “I miss you and the baby. As ever, your adoring Neil” followed by eleven big Xs. That “as ever, your adoring Neil” was the final phrase in every letter he sent all the sixteen years he was travelling. I knew my mother treasured these letters because she kept them for the rest of her life. Whenever the inevitable strains of marriage would temporarily overtake her and my dad, she’d read one or two of them, reliving the flush of their early love.

These letters kept me close to my dad even though Mom was the constant physical presence. Dad was “on the road” Monday to Friday, a travelling salesman perfecting his pitch as he worked solely on commission for Sutherland Press, his employer in St. Thomas, Ontario. He’d stop at every small business in his territory and convince the owners, under the guise of buying gas, a sandwich, a packet of Sweet Caporal cigarettes, or getting a haircut, to look at his samples.

“What do you think about this as a goodwill gesture for your customers?” he’d ask, as he opened his sample case, displaying anything on which an ad could fit — small screwdrivers, sewing kits, rulers, emery boards, key rings, pens, and pencils. The crown of his collection of goodies, however, was the common man’s art collection — calendars produced by Sutherland Press depicting fishing (“all the phases of the moon shown for best catching times” ) and hunting, dogs, cats, and monkeys, scenic vistas of mountain temples, cowboys on the range, ethereal nude nymphs rising innocently from a secluded pool to bask in the sun’s rays. He’d explain to my mother, “I always show them more than one line, so they have to make a choice. Otherwise if I have only one thing to offer, they can easily say no.”

Life on the road in the Depression years was competitive and he had to fight for survival for his small family. “Do you remember, Maw, when Lorraine was a baby, I’d shoot craps in the hotel at nights so you’d have money to buy orange juice for her?” he’d reminisce in later years. That tame love of gambling was disguised in the letters as “having a card game in the hotel in Peterborough” with fellow travelling salesmen like “Tiny” Mercer, Bill Mickelthwaite, and Chubby O’Toole, all peddling their particular “lines” in the same territory.

After we’d read through all three letters, the last of which had arrived only that morning, we’d open the Laura Secord candy box, where mother kept her photos. It was my job to lift off the lid bearing an embossed medallion of a stern woman in a starched bonnet. As I handed my mom each picture, I’d ask, “Who’s this, Mommy?” No matter how often she told me I’d ask each time, loving the predictability of her answers.

There’d be photos of my father in an argyle sweater, posing nonchalantly against a spiffy car, his arm around Mom in her very chic fur-collared coat (no doubt one she’d modelled for her former employer, the Spadina clothing manufacturer). Beside them stood two other couples, arms joined around one another’s waists, each person with one foot raised in the air, doing a kick-step.

“Oh, Lorraine, you know who that is. That’s Auntie Flo and Uncle Frank. And that’s Auntie Phil. Can’t you tell from her beautiful teeth? And that’s her boyfriend she went around with for years — Dimmie Woodie. Boy, how those two could Charleston!”

My first impressions of what it would be like to be grown up came from those photos. You had someone you loved with his arm around you, and you posed as if you were part of a chorus line, and you smiled the biggest smile you could manage. If the photos weren’t of people lined up against a car in a field, they often were of picnickers on a rocky island or on the sand at Balmy Beach mugging at the camera. It looked like it was fun all the time.

“Flo wasn’t smiling a few hours after that was taken,” Mom would recall solemnly, looking at a photo showing my smiling aunt sitting on a rocky incline. “When we were sleeping that night, lightning struck Bobby and Clare McLean’s island. Your aunt screamed blue murder!” I thought of the Auntie Flo who always gave me juice and homemade cookies as the smiling person in the photo. Now my mother was telling me of another Flo, one terrified of storms on a Haliburton island. Which was the real Flo? I was becoming aware that there existed other sides to being a grown up besides a smiling one.

My Grandmother La Branche with a softer look than I remembered from the only time she ever stayed with us.

The photos shot on the beach between Glen Manor Drive and Balsam Avenue were by far the majority in the chocolate box. Dad had taken a picture of Mother, looking a bit breathless in her black wool bathing suit with its attention-getting striped top, showing off her beautiful legs. One photo showed Auntie Flo’s husband Frank sitting on his beach blanket at Balmy Beach, looking cocky and confident, preoccupied with juggling a toothpick at the side of his mouth.

A handful of photos were sepia-toned, rather than black and white. In these, the subject was a matronly woman, sometimes sitting alone or sometimes with a girl in her late teens perched awkwardly on the older woman’s lap. That woman was my mother’s mother, whom I had never met. Then I looked at my own mother, sitting sideways on her mother’s lap, the short skirt again revealing Mom’s shapely legs. Her arm encircled her mother’s shoulders. Grandmother La Branche was smiling at the camera, one hand resting on my mother’s hip.

That photo prompted my mother to tell me the one story of her childhood in which her mother played a major role:

It was 1922. I was away at the French boarding school in Haileybury. I was about eleven. I could hardly wait for visiting day for my mother to arrive. She usually came once a month. I remember when she arrived I was always so proud of how she looked. She would be wearing one of those beautiful wide hats she designed herself. She’d just got there and we were sitting in the parlour. One of the nuns rushed in and frantically yelled at us. “Depechez-vous. Depechez-vous.” There was a huge forest fire heading toward us and we were to take shelter in the Cathedral. Once we got there, we thought we were safe, but then the fire reached it as well.

We ran outside and down the road to Lake Temiskaming. Even though it was early in the afternoon, it was dark because of the thick black smoke. Fireballs kept whizzing over our heads. We finally reached the lake and ran in with all the other people. There were animals standing beside us — cows, horses, sheep. My mother and I were in water up to our necks. Every once in a while she’d push my head under as the fireballs flew over us. Then she’d lift my head up again in the smoke so I could get some air. We were like that for about two hours. Lake Temiskaming is so cold in October. If it hadn’t been for my mother, I would have died.

When we finally were able to come on shore local people gave us some clothing and blankets. They even gave us milk taken right from the cows that had been standing in the water.

She would then pause, ending the story on the most poignant note of all.

“I remember. The milk was warm.”

That porcelain kitchen table was not always a site of such idyllic moments. One Saturday morning, there was a knock at our door.

“Lorraine, you go open it,” my parents instructed, knowing how much I liked to do that. Before me stood a woman and a man holding a small satchel.

“Well, this must be Lorraine,” he said as he patted my head.

The next thing I knew my father carried me to the kitchen and laid me out on the hard surface of the table. I was mystified but not frightened. I lay docile as they wrapped a white sheet around me. It was only when the man and woman reappeared with white masks over their mouths, eyes focused down on me, that I became apprehensive. The man, who in fact was the doctor, started to move his hands down toward my face. He was holding an apparatus resembling our toilet plunger minus the handle. He lowered it till it covered most of my face. I tried to push it away, but my father was holding down my arms. A strange odour overtook me as I struggled to breathe. Then all went dark. The ether had done its work.

Later I awoke — groggy and with a sore throat.

As was common with other Depression-era parents, mine couldn’t afford to take me to the hospital to have my tonsils out. Obviously, none of my parents’ generation had ever heard of “preparing” children for traumatic events.

When Dad was away, our time in the good weather was spent on the boardwalk, the beach, or Queen Street. My mother would wheel my pram or walk me over to Willow Avenue to Joyce and Auntie Ev Square’s house. Off we’d go in search of sun and chatter near Lake Ontario’s blue waters. Sometimes they’d sit on the beach. I’d love that because I could sit on the gritty, warm sand. As three-year-olds, Joyce and I would pour sand over one another’s legs. It formed a cozy, warm covering over our skin. Never still for long, we’d run from that sandy blanket to the water’s edge. For me, Lake Ontario was never too cold at fifty to sixty degrees Fahrenheit, because that’s the only way I experienced it. We’d paddle around the water’s edge and pack wet sand into tin moulds shaped like shells, lobsters, or starfish, and then turn them out near the shoreline. If a breeze came up, little waves would lick at our shapes until they crumbled and became one again with the shore. If any survived, we’d dust them with finer grains from our metal sand sifter. Finally, we’d dig a moat around them and fill it with water, but we could never get the water to stay there. It would slowly sink into the sand and merge with the lake once again. We could only accept the water’s ceaseless ebb and flow. As we grew older, Joyce and I graduated to larger pails. Then we could make high sand castles and decorate them with a flag made of Kleenex and a twig. They became the stuff of fairy tales.

Periodically, we’d look back at our mothers sitting at the edge of the boardwalk, talking animatedly, knitting small garments. We weren’t even curious as to what they were for. The hazy, wavy heat rising from the sand gave everything a rippled appearance. The sound of the water near us, mingled with our mothers’ girlish laughter, set up a gentle duet that I was never to hear anywhere else. Even the faint, fishy smell of the lake, which lingered on the hottest days, was welcome in its familiarity.

If it was too cool or windy, we’d walk west along Queen past Kresge’s and the enticing smells of the Gainsborough Delicatessen toward the Beach Theatre at Waverly Avenue for the big treat of the day — a Caulfield’s Dairy ice cream in a waffle cone. Dad had told me once that tutti-frutti was his favourite flavour. I loved the brash sound of that double name. But what a disappointment. I gagged on the hard pieces of chopped fruit. Another lesson learned — my parents’ tastes and mine didn’t always coincide.

There were few strangers at the Beach during the week. We always saw people we knew, either by sight or by name, anywhere along Queen between Woodbine and Neville Park. It was a self-contained community of respectable, decent families who lived and worked there and local characters who were fully accepted.

Even the shopkeepers were constant figures. Between Wineva and Hambly thrived a proverbial “nation of shopkeepers.” Mr. Littlefair and his sons presided over his butcher shop, with its sawdust-sprinkled floor and huge refrigerator along its back wall. He’d rhythmically wield that barbaric butcher knife over the stained wooden block and I’d marvel that he didn’t chop off his fingers. Mother would pick up pastry patty shells at Dawes Delicatessen and I’d anticipate her delicious chicken à la king with its small round of pastry sitting on top. At Young’s fruit and vegetable store — no flowers for sale at fruit stores then — I’d covetously eye the basket of new kittens, decidedly Siamese-looking and free for the asking.

Brown’s Confectionery Store, Ostrander’s Jewellers, and Wilkie’s Cigar Store were all in this block. The clerk at Wilkie’s, known as Old Man Mac, hid copies of Sunbathing Magazine behind Liberty, Colliers and the Saturday Evening Post. On the south side of Queen were Taylor’s Dry Cleaners that Hershy’s folks (who’d moved to a house at Wineva and Queen) owned, Clyde Thorpe’s hardware store, and Nova Fish and Chips. Mr. Nova, as I called him, was always behind the counter, white apron outlining his rotund body, tongs in hand, ready to pluck out the fish from the boiling oil. His chubby face was always florid, perspiration running down his forehead and hair in tight curls from the steam. The White Tower Cafe, a restaurant whose inside I never saw as a young child, was at the west end of that block. No restaurant burgers for us, though. My parents refused to eat hamburger meat that wasn’t cooked in our home. Besides, Dad never wanted to go out to a restaurant to eat.

“Your father eats out all week when he’s on the road,” my mother explained. “He looks forward to home-cooked meals when he’s here on weekends.” I can’t recall ever eating a restaurant meal until I was in high school. But my curiosity about having a restaurant hamburger increased as I grew older. It was only later that I found out why my parents had been so cautious.