Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 7

Life with Diane

“It was not enough for his story to be truthful, ‘it must be detailed as well.’”

— Nancy Miller, quoting Jean-Jacques Rousseau in The Ethics of Betrayal: Diary of a Memoirist

Diane is lying in her bed, surrounded by books, music boxes, and exquisite bed linens. She has taken off her oxygen mask for a while so we can talk without obstruction. Her cigarette habit has finally caught up with her and her faithful husband Bob is taking care of her so she can die at home. I feel in perfect communion with her. I ask her that when she’s in heaven, to save a place at the bridge table for me with her mother and mine. I remind her she has a brother there she never met, because he died shortly before birth. Now she’ll be able to get to know him. She smiles. “You know, I had forgotten all about him. Yes, that will be nice.”

She asks me for the third time what I want of hers. I finally give her an answer. “How about your handsome husband, Bob?” And we both laugh, she as much as her wasted lungs will allow. Seriously then, I choose a wooden music box with a laminated garden scene by Monet on the lid. When I open it, this delicate box plays an incongruous tune — “Tie a yellow ribbon round the old oak tree.” Again we both laugh, though hers turns into a cough this time, and I see her distress. I sit for a while in silence, a companion to my dearest companion through our last times together on earth.

I can’t imagine what my childhood would have been like without Diane. We were both seven years old when we connected. The Hillier family had just been transferred from Belleville. She lived at number 1 Hubbard in a lower fourplex and we were separated only by two similar fourplexes and the intangible differences that arise from living in an apartment or a house. We were soulmates from the beginning.

Until Di came on the scene, the only other girl in our block was Ruth Lawrence, the only and, ergo, spoilt (according to my mother’s theories) child of a young mother and older father. She was the apple of their eye. Ruth was younger than I. Nonetheless, the sight of her overflowing toy shelves aroused in me a burning envy, which she fuelled by exercising a supreme power over me. She decided, according to her daily whims, which toys I could or could not play with. Sometimes my fevered mind would scheme. “I’ll ask for one toy I don’t really want to play with. Maybe she’ll say no and point to another that I do want.” But I never got up the courage to go through with that in case she gave me the one I said I wanted and that I really didn’t want, and then I wouldn’t get the one I wanted … and oh, life got so complicated I would end up allowing her to play her despotic game.

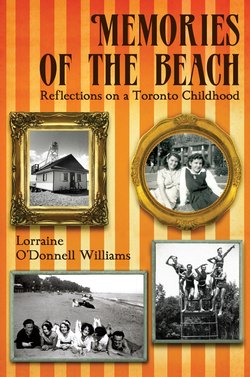

This is how Diane looked when I first met her — a little bit chubby and totally confident.

Diane and I treated one another so differently. We didn’t worry about toys — especially in the summer. The combination of boardwalk, beach, and lake was to us like a lover spreading out beautiful gifts for his beloved. We were water babies from our first breath. Cold water didn’t daunt us. We’d start swimming when the water reached 55 or 60 degrees Fahrenheit. The warmest Lake Ontario ever reached was about 75 degrees. We’d go in on the stony pebbles and rocks at the water’s edge, fighting to keep our balance. Then when we got to the top of our thighs, we could feel our legs going numb. That was the signal to dive under. Oh, the shock of that first plunge! Then, as we moved furiously around to distract ourselves from the frigid temperatures, the rest of our bodies gradually numbed, and we glided around in perfect happiness in our water kingdom.

In any spare time we had, we improvised to make up for our meagre stash of manufactured toys. Most of our playthings were made by human hands — ours! We’d get old cardboard boxes, cut windows and doors out, colour tied-back curtains on the cardboard beside the gaping window holes, then find old wallpaper or wrapping paper and glue it on the inside. We’d vary the pattern for each room as much as our supplies would allow. As we became more adept at cutting and pasting, instead of cutting out rectangular pieces for windows, we’d pencil them in on the cardboard, drawing a line down the middle. Then, we’d take a sharp knife, slice along the top and bottom lines, then down the centre. Voila! Shutters. We’d fold them back, creasing those fold lines so they’d stay open and not flop back to their natural resting place.

We’d divide the only floor into kitchen, bedroom, living room, and bathroom, each featuring a high ceiling. Next came the drawing and cutting out of mirrors and paintings from white paper and pasting them on the walls. The bedroom was the easiest to furnish. We’d use an empty wooden matchbox for a bed. We’d root around Mom and Auntie Flo’s sewing scraps for suitable materials, then hand-sew oval rugs (wall-to-wall was unheard of then), one bedspread, a pillow stuffed with cotton batting, and a cushion for a tiny chair precariously built of matchsticks. Sometimes an acorn turned into a baby and was laid in its crib, snuggled under a crudely cut piece of flannelette. Dishes and cutlery were a problem. The ones we owned were large tin sets from Japan, which were perfect for doll tea parties, but too large for our cardboard dollhouse. Then what would our pipe cleaner mother and father eat off of or with? We’d pretend that dinner was over and mother and father were sitting around the table (a cardboard circle top glued to an empty thread spool) talking. Devising solutions occupied as much of our time as the actual dollhouse play.

This early introduction into design blossomed as our play life went on. Over those early school years, we graduated from cardboard boxes to two-storey orange crates. But that demanded more decision-making. The orange crates could also be used for bookshelves or to form two ends of dresser drawers topped with a wooden board, covered with a piece of cherry-patterned oilcloth. I claimed one crate which I stood upended in my bedroom, becoming an altar with my tiny statue of the Blessed Virgin depicted as Bernadette had seen her at Lourdes. Mary was in blue, rosary in hand (was she praying to herself?) and crushing the serpent under her feet, resting on a globe of the world. Sometimes I’d interchange the Blessed Virgin with a statue of St. Joseph, both gifts from an alcoholic friend of my parents who always asked, “Pray for me.” I’d cover the crate with an old lace-edged tablecloth my mother willingly handed over for such a spiritual use. A tiny vigil lamp with a white candle and a bud vase filled with lilacs or forget-me-nots or pansies completed my bedroom shrine. I’d open my mother-of-pearl-covered First Communion prayer book, and concentrate on the mother-of-pearl crucifix inset into the inside front cover. As the breeze from the lake would came wafting in through the den to my bedroom, I spent truly holy moments contemplating the mysteries of blue Virgins and lily-clasping Josephs.

Although my piety grew, Diane’s interest and mine in handling orange crates loaded with slivers declined. We abandoned homemaking for fashion. Just as we’d created furniture, we graduated into fashion design. Now we made clothes for near-life-size baby dolls yanked from the bottom of old toy boxes. We ignored the round hole in their mouths and its imagined pleading for the tiny nursing bottle and transformed the dolls into children who wore clothes for seven-year-olds.

In our first attempts we wasted a lot of choice fabrics from our mothers’ scrap piles, either cutting patterns too small or sewing everything with the seams on the outside. Barred from the sewing machines, we hand-sewed everything. Stitches were crude — long, running ones of double thread. But they held the outfit together. Fortunately, we never had to make long pants since they weren’t that common for girls. To avoid pajama bottoms, we chose nighties. We mastered sewing proper armholes, necks, and side or back openings using an assortment of flannelettes, with pieces of torn white cotton sheets as the only relief. Our worst moments came when we had to use material that had once been someone’s pajamas or nightgown. It seemed icky to dress a rosebud-mouth baby doll in an evening gown made from Mr. Hillier’s pajama pants. The only exotic material we fought over — and Diane won, because it had belonged to her big sister Mayo — was a discarded leopard-print rayon blouse. Diane used up all the material so there was none left over for me. Although I thought her baby doll looked silly in her matching dress, cape, hat, and muff of leopard spots, I envied its “chic” contrast to the stripes or flowers of my doll’s heavy flannelette wardrobe.

Once we’d mastered the basic wardrobe, we indulged in an orgy of accessories. Our mothers’ button boxes were a storehouse of gems — if one considers rhinestone buttons gems. Searching through hundreds of items and pairing a navy blouse with five buttons decorated with painted sailboats or attaching one large mother-of-pearl button at the neck of a satin evening gown made the labour worthwhile. We also rifled through the old candy tin containing “trimmings.” We’d claim odd bits of coloured lace, binding tape, net, and organdy. Soon every outfit had trimming. We used anything we could find to add a stronger fashion statement. Sometimes it was a soft grey-white seagull feather. Sometimes it was an extra earring from Auntie Flo. I even found a miniature rosary — it belonged to that nun doll I once had — and draped it as a necklace around the doll’s neck.

Even when Diane was not around, I would sit for hours on the front veranda, the willow tree rustling in the breeze, the waves lapping on the beach, contentedly sewing away on what were essentially duplicates of every other outfit I’d made.

“Want some lemonade?” Mom would come out and ask.

“Yes, please.”

I never recall any comment about what I was doing or how it looked. But compliments were not the style in our house, and my sense of worth in this — or any other endeavour — came from my own satisfaction doing it.

Where did all those grown-up outfits go? I fear that the constant strain of putting on and taking off was too much even for those double threaded seams. And the time was coming when Diane and I would be separated for two years and that would mark the end of our first venture into couture design.