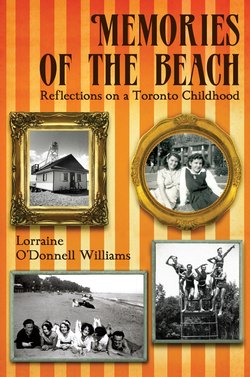

Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 6

The Boardwalk, the Beach, and the Lake

To see a world in a grain of sand, And a heaven in a wild flower; Hold infinity in the palm of your hand, And eternity in an hour.

— William Blake, “Auguries of Innocence”

Most of my days began and ended with the boardwalk, the beach, and the lake. Whether it was getting up for school or lazing around on a weekend, my first waking moments were spent tiptoeing across my room, careful not to disturb my sister Susie in the other twin bed. I’d head for the door in the den.

The door opened onto a wide, open upstairs veranda. It looked out past our weeping willow to the boardwalk, the beach, and the lake. By 7:30 a.m. a few early risers would be out walking their dogs — no requirement then to keep them on leashes. Each dog would sniff around our big willow, catch the scent of our cocker spaniel, Ginger, and leave a token of esteem. No joggers bounded by. That form of exercise was not common. I’d see Jake, one of our local characters, a retired policeman who did speed walking every day, rain or shine. His determined stance and jutting chin as he strode made him unmistakable. On the beach, the sand was rounded into slight gray curvatures A few sparrows pecked for remnants from the previous day’s picnickers. At the shore, gulls were swooping down to grab small fish, most of which were already dead or in their death throes, that had washed up on the shore.

In the fall, I’d walk carefully on the top veranda because its tin floor was covered with a pile of nuts, placed there by my father to ripen. They were the fruit of our weekend rides into the country looking for beech, hickory, and other specimens growing wild in bountiful southern Ontario farmlands.

“Neil, that makes an awful mess,” my mother would complain mildly.

“Aw, Maw, you loved picking them. No sense throwing them out now before we’ve had a chance to eat them,” he’d josh her.

Out on the lake, the sun was just beginning its climb from east to west. Tankers on the distant horizon would be making their way to Rochester or other unknown ports. A few faraway commercial fishing boats might be bobbing noiselessly in the breeze, competing for lake whitefish, yellow perch, and American eel. The lake at this hour had a washed out blue-grey cast to it. It hadn’t yet established contact with the sky that would share its deeper blue with it. To the west, I could glimpse the Lifesaving Station at the foot of Leuty Avenue. Even then, it was a Beach icon. Built in 1920, it had a simple design — a single-storey wooden rectangular box with an observation tower. Perhaps it was an afterthought by its architect, Alfred Chapman, who had created the splendid Ontario Pavilion at the Canadian National Exhibition and the Sunnyside Bathing Pavilion. Nonetheless it symbolized to decades of Beach residents their long-standing connection with the waterfront.

When I stepped out on the top veranda, I could tell in an instant what the day’s weather would be like. If it was close to summer and there was a fishy smell, I knew it would be humid. If there were already gentle ridges on the water, a refreshing breeze would keep us cool. Sometimes huge swells pounded the shore roughly every twenty seconds, taking what seemed like forever to unfurl. After retreating into the lake, they’d leave behind a smooth expanse of three or four feet of sandy lake bottom. When that happened I knew that by 8:00 a.m. the lifesaving station would be flying the undertow flag. Those who were sons and daughters of the Beach knew not to ignore it. Every year we’d see at least one swimmer disregard the warning, only to be swept under by a force more powerful than he. “There’s some poor soul who went out when he shouldn’t have,” my mother would warn. As we got older, we’d run to the lifesaving station, watching exhausted lifeguards administer artificial respiration for what felt like hours, their attempts too often futile.

The Leuty Lifesaving Station, an icon of the Beach, has been photographed at every possible time of day, in every season of the year.

Other days there would be no sun. The lake, angry under a grey swirling sky, would be dotted with fierce drops of rain creating millions of perforations in the unsettled surface. Even the gulls would avoid the sullen face of the waters. I loved the lake, even in its angry inhospitable mood. It held as much wonder for me as when I’d wake to find an infinity of golden lights glistening off its ripples as the sun danced on its surface. My day truly began with my morning communion with the lake.

The sand had its changing moods, as well. Throughout the years we lived there, the lake inched its way toward the boardwalk. Finally one year, the water actually reached under the boardwalk. One day we found two bloated dead rats in our window well. “That’s from the lake coming up so close,” my dad explained, “It’s driving out all the rats who live underneath the boardwalk.” I hadn’t known any rats did live underneath! It took some time until I overcame my queasiness.

Finally, the City responded to the near-erosion of the beach. Earlier attempts in 1926 with wooden groynes had been successful. So they tried it again. Workers spent months putting in huge groynes — cement ones, this time — that stretched like huge fingers on the remaining beach and ran vertically into the lake. They ruined the look of the beach. I was forced to make decisions I’d never had to make before. Shall I sit on this side of the groyne or on the other side? It was as if the beach was divided into small lots and you had to decide where to place your beach towel and deck chair. Sitting or lying on the beach was never again as simple. The good part was that the sand did build up over the years. The groynes became invisible.

The sand had other characteristics. When it rained, only the top layer got wet, heavier like icing on a cake. If you lifted the top layer, the grains underneath were still separate and speckled and dry. On a hot day, your feet could get burned if you didn’t protect them while getting from the boardwalk to the water. If I was too lazy to fetch my sandals, I had a solution to escape pain. As I moved each foot, I dug it deep under the sand’s surface to the cooler sand underneath. Later, as a teenager, I made another discovery. If I had fierce cramps at the beginning of my monthly period, I could get rid of them by lying down on my stomach against the warm sand. It would mould itself around my tummy, and I’d fall asleep. When I awoke the pain was gone. “Oh sand! Oh healer!” I’d chant to myself.

Being inland water, Lake Ontario had no seashells along the shoreline. But I would find other treasures — pieces of smoky blue, white, and green glass rubbed smooth by the motion of water over sand. Or sometimes it was a piece of mica mysteriously situated at the shore’s edge or a small cream-coloured stone with red markings and hints of gold. Other times, Sue and I would walk up and down the length of the shore looking for flat “skipping stones,” learning by trial and error how to bend low enough so they’d skip over the water, sometimes as many as six times. When my baby brother Neilly — born when I was eight — became older he wanted to skip stones with us. Sue and I would discourage him because the ones he threw were just as likely to end up bouncing off of us instead of off the lake. We didn’t suffer careless stone throwing lightly, ever since we’d heard one of the few childhood stories my mother told:

“I was playing on the beach just like you, and some bad boys came along and started throwing stones at me. My nose got broken. Did it ever hurt.” Whenever she told that story, we could almost feel the bones breaking in our noses.

And so the cycles of the seasons went. After the long winter when spring arrived, I’d return to the routine of sunning myself on the top veranda. One Saturday morning in June, while looking out over the calm pale water, I detected from the corner of my eye a faint motion beneath the surface close to shore.

Then, a second time I saw the water ripple and the outline of an enormous fish — probably a whitefish. It flopped back and forth, as if in some distress. I’d never seen a fish this large in Lake Ontario, only silver minnows stranded on shore and promptly scooped up by sharp-sighted sea gulls.

I watched, mesmerized. Then, snapping out of it, I rushed into the house. “Daddy, Daddy, come quick. There’s a huge fish in the lake!”

My father, the inveterate fisherman, came bounding up the stairs to the second-storey veranda. He stared with the same fascination as I had. Then his body sprang into action. “Keep your eye on it, while I get my fishing rod,” he instructed. In the space of less than ten minutes, he retrieved his casting rod from the garage, put a lure on it, and rushed down to the shoreline. It was no use, however. Although his aim was accurate, the fish didn’t even glance in the direction of the lure. He said afterwards it was just as well. The fish was probably sick!

I felt disappointment for my father, but privately I was relieved. My lake must not spin off new activities such as recreational fishing from the shore. It would have been an intrusion for the Beach district to become a fisherman’s playground. I’d worked out an intimate relationship with this lake, and I wasn’t willing to have new dimensions introduced.