Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Growing in Mystery

“The most beautiful and most profound emotion one can experience is the sensation of the mystical … It is the source of all true art and science.”

— Albert Einstein

One Sunday afternoon before I turned six, my mother took me up to our parish church, St. John’s on Kingston Road at Glen Manor Drive, in the late afternoon. She told me we were going to “benediction.” It was particularly special because it was the first time I remember since the birth of my sister Suzanne two years earlier that she’d taken me on my own anywhere. Once inside the church, I was overcome with sensory delight — the sweet odour of incense, the glow of the monstrance mounted high above the altar like a golden sunburst, and the voices of children singing in some strange language.

“Tantum ergo, Sacramentum.”

“Mommy, when can I sit with those children up there?” I asked, pointing to the front rows.

“When you start school in the fall,” came her whispered reply.

That late afternoon in May was my introduction to Mystery, and for the rest of my life I attempted to probe its riches. My initial yearning to go back into that church, with its soft lights and incense, was more than fulfilled during my six years at St. John’s Catholic School. The two-storey boxy red brick building, built in 1910, had replaced a temporary school erected in 1909 at 21 Main Street and had been administered since 1917 by the Sisters of St. Joseph. The school consisted of four classrooms plus two double portables at the rear. On its left side a massive schoolyard stretched all the way north to Lyall Avenue. On the right was St. John’s Catholic Church and rectory where the respected pastor, Father Denis O’Connor (later to be Monsignor), and his curate, Father Driscoll, had their home and offices. The school and the church operated as a unit.

I experienced this close connection between church and school from my first day. Father O’Connor would visit our grade one class regularly, and go over our catechism lessons with us. From the lips of Sister Mary Rita, my grade one teacher (Toronto Catholic schools had no kindergarten then), we experienced our first deep encounter with a loving God. And we learned what our purpose was in life from the catechism:

“Why were you born?”

“To know, love, and serve God and be happy with Him in heaven.”

For me, Sister Mary Rita was a stand-in for God. It was my first experience with such a fullness of sweetness and patience, and it had a salutary, calming effect on me. I think she loved me, too, because within the second month of school she chose me as leader of the rhythm band, the most privileged position among grade one students. Even my uniform was special. It was the only one with a flowing redlined cape. I alone wielded a baton. My pillbox hat was specially decorated. What a thrill to be singled out and not to have any idea why! That, too, was mystery.

St. John’s School was a no-nonsense structure with no funds for landscaping to soften it. Its beauty was inside.

On the first day of school I was fascinated by the huge picture of planet Earth viewed from space that was hanging at the front of the classroom. The sky around it was a brilliant azure blue. My eyes kept being drawn to a depth in those skies that I could never completely plumb. In the farthest reaches of that rich space could be seen hints of other planetary bodies. Underneath the picture were the words: “God created the Universe.”

Every school day began the same. Sister had us stand up, make the sign of the cross, and say our morning offering — offering up to God all the actions and thoughts of our day, large and small, as a form of prayer. The first subject was religion. Sister Mary Rita started at the very beginning — with Genesis and the creation of the world. The next week she flipped to another picture on the chart. At first I was displeased. I was sure I’d never see anything more beautiful than that azure universe. But an equally compelling picture replaced it. A magnificent angel with full white wings hovered protectively over two peasant children crossing a rickety bridge. A raging river flowed below then. The little boy and girl, clasping their newly gathered wildflowers, were unaware of danger lurking below. The presence of their loving guardian angel coupled with their own serenity and innocence instantly convinced me no danger would befall them — ever. Hearing repeatedly from Sister Mary Rita that God had created the angels and given them charge over everyone in the world reassured me. My personal angel would always be there guarding me, as well. I, too, would be shielded forever in the soft folds of those protective wings. Sister taught us a new prayer I was to say every day of my life: “Oh angel of God, my guardian dear. To whom His love commits me here. Ever this night [day] be at my side. To light, to guard, to rule, and guide.”

The mystery of the God who made us and loved us deepened in me. Sometimes, though, God’s rules seemed strange. This was particularly so as I approached the high point of grade one — making my first Holy Communion. By spring, we had rehearsed exhaustively. We were also given serious instruction. “Before you go to your first confession, be sure to do a thorough examination of your conscience for any sins.” This was followed by “Don’t tell anyone else what sins you confessed or what your penance was.” And finally, “Don’t be afraid to go in the confessional. The priest is merely taking the place of our Lord. It’s really Jesus who will forgive you.” Then the rider, “If you’re truly sorry for your sins and if you promise not to commit them again, and if you promise to make amends.” This last condition was explained with examples such as “giving your sister or brother one of your toys if you deliberately damaged one of theirs.”

Although a few of the six-year-old boys admitted they’d be scared to go into the dark confessional, even if it was friendly Father O’Connor in there, I had no fear. For me, it only enhanced the mystery to kneel in a dark closet-type cubbyhole, unseen by the priest as I whispered my confession. On the day of our first confession, Sister Mary Rita marched us over to the church. I entered the confessional and knelt. Father O’Connor pulled back the little sliding panel. He was sitting in full profile, eyes averted, cupping his ear with his fingers as he inclined his head toward the screen to better hear me.

“Bless me Father for I have sinned. This is my first confession … I have talked in church three times, and I have missed my morning prayers almost every morning.” Until the day I left St. John’s School, I think this was to be the full gamut of my sinning life every second Saturday when I went to confession. By grade two, I’d get so bored with myself I’d take out my little prayer book at night and carefully reread the children’s “Examination of Conscience.” Maybe I’d find some new sins I could claim. Had I been disobedient? Had I taken an oath or God’s name in vain? Had I missed Mass on Sunday? Unthinkable. Had I stolen anything? Had I had any impure thoughts? (I was to make up for it later in life.) Had I venerated any false objects? I never could find any new temptations on my spiritual journey. I believe I forced myself to forget my morning prayers (never the night ones) so at least I’d have something to confess.

“Don’t Break Your Fast.” The First Communion class was warned about this day after day. “You cannot have any food or water from midnight before your First Communion Sunday.” Even the miracle of grade one pupils having some appreciation of the great mystery of transubstantiation — bread and wine actually being turned into the body and blood of Christ — paled before the terrible sacrilege of allowing food and drink to touch our lips anytime after midnight preceding the big day. I became so preoccupied with Not Breaking My Fast that it took on alarming proportions. I, who never woke during the night, started to worry, What if I need a drink of water in the middle of the night and forget I’m fasting and Break My Fast? All I could picture was arriving at the school on that beautiful May morning in my starched white dress, gloves, and veil with its precious crown of seed pearls and green artificial leaves, and being taken aside and told by my adored Sister Mary Rita, “Sorry, dear, but you’ll have to wait till next week. I warned you not to break your fast.”

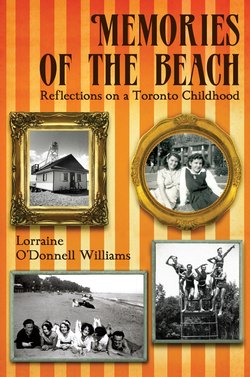

Father (later Monsignor) Denis O’Connor looks over the 1939 Communion class.

First Communion day finally arrived. I hadn’t Broken My Fast. I knew not to chew the sacred host when it went into my mouth, but rather to swallow it immediately. My parents dropped me off at the school where the Sisters lined us up properly for the procession into the church. I was still congratulating myself. I hadn’t Broken My Fast. It felt a thousand times better than Not Stepping on a Crack or You’ll Break Your Mother’s Back. However, my classmate Bernie Martin was not so fortunate. He looked spiffy in his new navy blue suit with short pants and his carnation boutonniere. As Sister straightened us out in line, she suddenly pulled Bernie out from his place.

“Bernard, what do you have in your mouth?”

“Gum, Sister,” came the innocent reply.

A stricken look appeared on Sister’s face. She told Bernie to sit at his desk, then hustled to the back for a hurried, anxious conference with our school principal, Sister Beatrice. Every so often they’d send a searching look Bernie’s way. He was oblivious to it all. If anything, he was chewing faster and faster, making the most of this single opportunity to chew gum right in a classroom.

My mind was slowly coming around to what was the problem. True, he wasn’t swallowing the gum, so in that sense he hadn’t Broken His Fast, but I could smell that tangy coating on the stick of Dentyne. Maybe my hunger pangs were sharpening my senses. Where did that tangy saliva end up? I knew and so did the nuns — in Bernie’s stomach! That kind gesture by a family member to help little Bernie avoid the rumblings of his impatient stomach had created a crisis. Only consultation with Father O’Connor could solve it. The principal rushed over to the rectory. A few minutes later, she breathlessly reappeared and whispered to Sister Mary Rita “special dispensation,” whatever that meant.

Little Bernie never knew of the crisis he’d created. For my part, I didn’t once break either the spirit or letter of the law around fasting until I was in university, where someone gave me a formula how to manipulate it. All I had to do was assume I was still on daylight savings time in the fall, even though the time had changed, or calculate when it would be midnight in British Columbia, even if I was going to Communion in Toronto, giving me a three-hour advantage. All that fiddling around, bending the rules as I got older paled beside one story an Irish friend told me. After Vatican Two, fasting rules had been relaxed. She was finding it difficult to switch from the old rules.

“Mind you,” she informed me, “In Ireland you couldn’t even lick a postage stamp before Communion or you were Breaking Your Fast.”

I remember my reaction, “How stupid.” I knew in my heart my beloved Sister Mary Rita might struggle over Dentyne gum, but never over a postage stamp.

Unfortunately, as much as I basked in the love and sentimentality of my introduction to things spiritual, it didn’t take long for a rebellious side of my nature to surface.