Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 4

Being Bad

“What demon possessed me that I behaved so well?”

— Elisabeth Harvor, “Through the Fields of Tall Grasses” in Let Me Be the One

The heavy rain had finally stopped on that Saturday of the Victoria Day holiday. The mothers were on Queen Street picking up their pre-ordered hams at Littlefair’s and sweet potatoes at the Power Store. I was romping in front of our new home — the top unit in a Hammersmith Avenue fourplex — with some neighbourhood kids. We moved there from Beech Avenue in 1938 — the year I’d started school. It was from that Hammersmith sidewalk that the neighbourhood had gathered in October to watch a giant twin-motor Lockheed thunder out of the Malton airport, marking the inauguration of Trans-Canada Airline’s Vancouver– Montreal express service. I felt so grown-up to witness this with adults. Most activities between adults and children had clearly defined limits.

That May day, there was nothing much to do except float old sticks in the rivulets running down the pavement curbs. The McClelland kids from down the street had led us in marching fashion to their backyard. The grass there hadn’t yet been able to absorb the earlier downpour and the backyard turned increasingly mucky as we aimlessly sloshed around the yard in circles. Mrs. McClelland’s linens were hung on the clothesline, a stark white contrast to the muddy landscape.

As I plodded around the yard, my six-year-old feet perspiring in rubber boots, I wove my way through Mrs. McClelland’s bleached linens hanging above us. The towels inflicted a cold, clammy slap on my face as I pushed through them.

All of a sudden I felt a powerful urge to take over leadership of these straggly six- to eight-year-olds. It was a strong emotion I’ve never experienced before. With no premeditation, I reached up to the clothesline and begin pulling down one item after another, not even bothering to remove the wooden clothes pegs. As I wrenched the linens, some of the pegs twirled upside down on the line, as if staring at the havoc being wrought. With increasing fury, I moved from one end of each clothesline to the other. There was no sound except my huffing and puffing as I pulled each item down. There was a force within me that allowed no opposition. It moved through my body like a bolt of electricity. It was almost as if I was detached from that body. I watched myself run back and forth, my feet pounding those sheets deeper and deeper into the slushy ground. When I was sure they were all soiled, I stomped over them again to remove any vestige of that pristine whiteness.

My companions stood helpless. Even the two McClelland children were still.

Just as suddenly as I began, I dashed toward home. The others dispersed quickly. I ran up the stairs to our apartment and hid in the bathroom. Inside I regained control, then walked into the living room where my father was sitting. Daddy had just put my baby sister Suzanne to sleep in her crib in my parents’ bedroom. He was chuckling at a cartoon in his Saturday Evening Post. I got out my pencil and began connecting the dots in my colouring book. My mother was still out shopping, so we both sat there quietly, whiling away the time.

Some time later the doorbell rang. Daddy went to the top of the stairs and pushed the buzzer that opens the door. I heard Mrs. McClelland at the bottom of the stairs. She had barely started to speak when I rushed to the hallway and clutched my father’s legs.

“I didn’t do it, Daddy, I didn’t do it.”

I was sobbing so hard he could barely hear Mrs. McClelland, who had yet to explain why she was there. He signalled to me to go back to the living room and heard Mrs. McClelland out. After she left, he walked slowly back into the living room. This was a new situation for him. My mother was the disciplinarian, because he was away all week, on the road. With a sad look, he sat down, motioned me to come over and lifted me across his lap.

“I’m sorry, Lorraine, but I’ll have to spank you.”

He gave me six or seven slaps on my bottom. They didn’t hurt that much, but I cried because my beloved daddy had never spanked me before. I turned my tear-streaked face back to give him a look — reproving? astonished? — and saw tears in his eyes. I became confused. If it made him sad to spank me, why did he do it? A terrible thought occurred: was he afraid my mother would bawl him out when she returned if he hadn’t punished me?

Daddy resumed his reading. I turned to my cutouts of Princess Elizabeth and Margaret Rose. Sue woke up just as my mother returned and my mother’s attention was directed at her. Eventually, I overheard my parents conversing in low voices at the kitchen table. They were discussing my behaviour. Yet it was so strange. I felt no guilt over what I’d done. It was as if it didn’t belong to me. The Lorraine I knew was a good girl, a child who rarely disobeyed because it rarely occurred to her to do so.

My parents re-entered the living room, mother carrying Sue. In a very serious tone, she addressed me: “Your father and I have decided that you must stay inside for a full week. You can’t go outdoors for any reason. However, you can play on our upstairs veranda if you wish.”

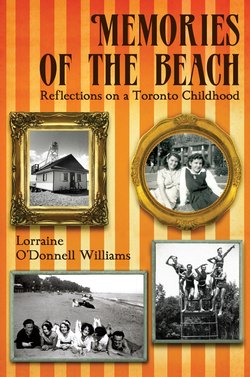

My baby sister Suzanne and I in front of the Hammersmith Avenue fourplex in which we lived for a short time.

My father stood by, a silent witness. I said nothing, but I was thinking and feeling, Why this? I’ve already had a spanking.

The days crept by, shapeless and boring. On the third day, I took my crayons and colouring books outside on the veranda. I lay down on the rough cocoa matting covering the tin floor. Spring had come overnight, and the warm sun heated up the floor. After I’d finished colouring Cinderella and her pumpkin coach, I stood up, holding the stub of my crayon and leaned over the railing to look up and down Hammersmith. Kids were racing on tricycles or rolling hoops down the street. Those fortunate enough to own roller skates traced endless ovals around their driveways. I could see all this, but their voices were faint as they rose in the warm air.

By now the tin floor of the veranda was radiating heat from the reflected sun. As I leaned over, I accidentally dropped the bit of crayon I was holding onto the tin ledge extending beyond the railing. I watched in surprise as it took only a few minutes for the sun to melt it. Where the crayon was, there was now a dull red circular stain. I went back to my crayon box, picked out a piece of yellow and deliberately dropped it a few inches from the first. Again, an amazing display of liquid colour. An edge of the yellow inched its way toward the red, and a new splotch of colour emerged.

My appetite was whetted now. The temperature stayed unseasonably hot. I spent the week fishing out crayon fragments from my cigar-box container and peeling off their paper covers before I dropped them. The reds and blues and yellows were the best. The blacks and browns merged into ugly stains, which frightened me. I created an infinity of forms and colours and designs. None had any particular meaning to me, but there was enchantment in seeing the different shapes they assumed as they flowed into one another.

The week passed as if I was in a trance. By the time my confinement was ended, I’d used up all of my bright colours. My parents made no comment on the patterns the sun and I created on the veranda. Did they ever actually notice them? No one mentioned Mrs. McClelland’s laundry. It was a long time before I ever did anything bad again.

My grandmother La Branche would have seen it differently. I only saw her in person twice. The first time was in the spring of 1940. I was in my bedroom in the Hammersmith fourplex. The curtained French doors separating my bedroom (originally the dining room) from the living room were closed. It was assumed I was asleep, but I heard voices. When I crept out of my four-poster with its decal of Tom, Tom the piper’s son on the headboard, I parted the curtain to peek at some visitors. I could see the smooth brow and downcast eyes of a young boy about my age, who I was later told was Donnie. He was playing with my collection of cardboard Second World War planes I’d pasted together from the back of a cereal box. Those planes had been the first connection I made to an event several months earlier. I’d been sitting with my parents listening to the radio as a voice announced, “This is London calling. Britain is at war with Germany!”

A handsome mustached man sat on our chesterfield, leaning toward the boy. (I learned years later that this was his “love child,” a euphemism used by my parents when they talked of him.) Smoke from the man’s cigarette rose from his stained fingers. My parents were also sitting on the chesterfield, my father’s hand resting on my mother’s knee. I could see her beautiful legs, which were her pride.

That older lady in the chair must be my grandmother, I thought. How come I’m seven and have never met you? Her hair was bountiful, just as in that early photo of my mother and her. I can’t remember what her voice sounded like, but I did hear Uncle Dolph and my parents talking. I thought, Where are your beautiful hats, Grandmother, that my mother told me you always wore? Then I returned to bed, hoping Donnie would treat my fragile cardboard planes carefully.

Less than three months after that, I finally did meet Grandmother La Branche face to face. She stayed with us for two nights. My mother as ill with a recently diagnosed stomach ulcer. It was a Saturday morning and I dressed, ate my cereal, and set out to call on my best friend, Patsy Carson.

“Where are you going, Lorraine?” my grandmother whispered so as not to waken my sleeping parents or baby sister.

“Out to play.”

“There’s no one to play with now. It’s only nine in the morning.”

“Well, I’m going to call for Patsy.”

“You will not call on anyone this early on a Saturday morning.”

I ignored her command and walked out the door. I knew my weekend routine better than this stranger. I knocked on Patsy’s door, praying her brother Kenny wouldn’t answer because he always threatened to beat me up. After a long time, Mrs. Carson came to the door, casting a dubious look at me. She was a Jehovah’s Witness and wasn’t keen on Catholics.

“No, Lorraine. Patsy’s still in bed. It’s only nine, isn’t it? Come back around ten.”

I returned to the fourplex.

“You called on your friend, didn’t you?”

“Yes.”

“I told you not to knock on anyone’s door this early in the morning and you disobeyed. Come here.”

I moved hesitantly to my grandmother. She put me over her knee, pulled up my dress and delivered hard, deliberate blows to my bottom. I cried bitterly — not with pain, but because of the indignity. She lifted me off her knee, straightened my dress, looked me in the eye with cold disinterest, and warned, “Don’t you ever tell your mother I had to spank you.”

This day marked the start of a habit of mine — withholding things from my mother for fear it would rob her of something she needed to hang on to. In this instance, she had had so little “mother” in her life I couldn’t risk damaging her image of that mother.

That was the first and last contact I ever had with Grandmother La Branche. I never was convinced I’d done anything bad. Even when Mother got that phone call from Ottawa four months later, stating that her mother had dropped dead of a heart attack, I felt nothing for my grandmother. But I cried for my mother as I heard her weeping.

My mother had other reasons to weep. Unbeknownst to me, my parents were struggling financially to keep their family of four together. Out of the blue I was informed that the following week, we’d be moving to a new house. My parents would show me the route home from school to the new address. More curious was the news that my Auntie Flo and Uncle Frank would be sharing the house with us. I had little chance to consider the upcoming change, other than to wonder what was going to happen to my art creations, indelibly inscribed in melted crayon on the veranda’s tin floor?