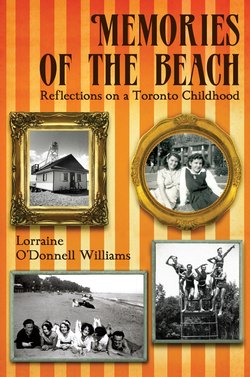

Читать книгу Memories of the Beach - Lorraine O'Donnell Williams - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Growing Up on the Boardwalk

Every man has within himself the entire human condition.

— David Shields, “Reality, Persona” in Truth in Nonfiction

Today The Beach neighbourhood is considered a safe stable place for busy Torontonians to live and raise a family. It is a trendy oasis of relaxation, and a refuge from the summer humidity that can wither city dwellers. But in 1793 when the Ashbridge family started to farm there, it was boggy, buggy, and plain hard work. The family, who’d moved there from Philadelphia in 1793 when John Graves Simcoe was lieutenant-governor, was determined to persevere in civilizing this lakefront wasteland. By the 1850s, other pioneers had joined them, including a settler named Joseph Williams. Williams bought a farm near the present-day Queen Street and Lee Avenue area and named it Kew Farms. Ever a man of enterprise, he designated a sector of it as The Canadian Kew Gardens. Contemporary documents described it as “a pretty pleasure ground of twenty acres, fifteen in bush, fronting on the open lake.” It offered “innocent amusements in great variety, including dancing,” and “temperate drinks, but no Spirituous Liquors.” The resourceful Williams instead sold his own milk and buttermilk as “the temperate drinks.”

The Beach area grew as the public became increasingly interested in its developing attractions. In 1876, a new subdivision between Silver Birch and Balsam Avenues reserved a “private promenade” on the waterfront for lot buyers. Streetcar and steamer service became available. The Toronto Gravel and Concrete Company built a tramway along the south side of Kingston Road. Horse-drawn trams brought picnickers to Woodbine Park (site of the first Woodbine Rack Track). New streets laid out in Balmy Beach Park bore the name of trees. (Veteran Beachers to this day maintain if you didn’t live on a street named after a tree you weren’t really a son or daughter of the Beach.) Still, life was not entirely civilized. People who went to work on winter mornings to downtown Toronto had to have a lantern which they left in a little shed at Woodbine Avenue. When they returned at night, they’d pick up their lantern, light it, and walk home.

Thomas O’Connor, a Catholic layman and benefactor of the Sisters of St. Joseph, was another Torontonian who owned a huge block of lakefront land. He bequeathed his farm, consisting of forty acres of land and twenty-four acres of water lots stretching from the lake to Queen Street East, from Leuty to MacLean Avenues to the St. Joseph congregation. After his death in 1895, the Sisters farmed the area as a profitable dairy and garden produce source. They used the income to maintain one of their major projects in the city — the House of Providence on Power Street, a huge institution for the indigent, sick, and aged. Finally, in 1906 the Sisters decided to sell the fertile farm site and establish a new farm on St. Clair Avenue East.

In a short-sighted decision, Toronto City Council declined to buy it because they considered it too expensive. The Sisters sold the property to Harry and Mabel Dorsey in 1908 for the sum of $165,000. By that time this eastern section had a population of about 5,000. It was developing into a year-round settlement with a school and churches. This growth was initially the result of the Toronto Railway Company’s expansion of service. It had installed streetcar tracks along Queen to Balsam in 1891 — for summer use only. Then, in 1901 East Toronto was incorporated into the City proper. By 1900 a third of the 287 lakefront homes east of Woodbine were no longer merely summer cottage escapes, but were occupied on a permanent basis. Queen Street was gradually extended past the R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant (known to locals as the Water Works and site of an illegal driving range to many aspiring young golfers). They had no inkling that in future years it would be celebrated in Michael Ondaatje’s novel, In the Skin of a Lion. Queen East ended at Fallingbrook Avenue and the Hundred Steps, at whose base was a small dance pavilion. The Dorseys recognized the land’s potential. There’d already been a series of short-lived amusement parks at different locales along the lake. They had a vision of an amusement park on the site patterned after New York’s Dreamland. They invested $600,000 to build the largest park with the most attractions ever put in the Beach area. In March of that year, a contest was held to choose a name for it. It opened June 1, 1907 as Scarboro Beach Park. It had everything that Coney Island ever had! There was a bandstand and a scenic railway that took visitors all around the grounds. the Shoot the Chutes ride had an opening underneath the spectators’ walkway for the boats. There was a multitude of choices — the Whirl of Pleasure, the Disasters Presentations, and the Electroscope, a bathhouse, the Scarboro Inn restaurant, and a carousel. Amidst the other hundred attractions the extremely long roller coaster ride proved popular, as did the Bump the Bumps Slide, Shoot the Chutes, and the Tunnel of Love. Performers used the thirty-eight-metre-high tower for daredevil acts. A miniature steamship train transported merrymakers all around the grounds. At night, thousands of lights decorated the park. Families would gather in their canoes and rowboats at the lakeshore to listen to concerts. Professional lacrosse (officially designated as Canada’s sole national game until 1994) and other sports were played at the athletic grounds, which featured a wooden velodrome. That interest in sports was to remain constant, with the Beach being the home of many softball, water sports, and tennis championship teams through the decades. The first public exhibition flights in Canada were made there by Charles Willard in September 1909. After almost two glorious decades, the amusement park closed on September 12, 1925.

House of Providence, Power Street looking north to St. Paul’s Basilica. Food for the city’s indigents was supplied by its huge dairy and produce farm on the future site of the Scarboro Beach Amusement Park.

1927 Aerial view of Scarboro Beach Amusement Park. It was a drawing card for thousands to the Beach every summer.

The City had not been idle during this time. After the Dorsey purchase and the subsequent success of its amusement park, it started accumulating other parcels of land on the lake, including the grounds and adjoining properties of Joseph Williams and designated it as Toronto Parks’ own Kew Gardens. Eventually all of the waterfront lands from Woodbine Avenue to Balsam were transformed into well-manicured green parks with plenty of recreational facilities fronted by a three-and-a-half-kilometre boardwalk. The park area, known as Kew Beach Park and Balmy Beach Park was eventually divided into four — Woodbine, Kew Beach, Scarboro Beach, and Balmy.

There was one city-owned exception to the designation of all this acreage as parkland. There was a short block on the south side of Hubbard Boulevard. It ran along the boardwalk west from the bottom of Wineva Avenue to the bottom of Hammersmith. It was called Hubbard Boulevard and it was in the house at number 13 where I spent my childhood. Our house was built on the site of that amusement park which had been a place of happiness for so many thousands.

Beach residents were full of pride in 1939 when King George VI and Queen Elizabeth officiated at the King’s Plate run at the Woodbine Race Track.

Sometime after the seventies, the area, always known as the Beach, began to be referred to as the Beaches. For a couple of decades, residents argued as to the proper designation. Finally, a plebiscite by residents in the spring of 2006 decided the issue. On April 18 it was announced that the traditional name, the Beach, had won. Now it was official.

This memoir is a celebration of the Beach and its role in my life and the lives of ordinary Beach people who were moving from the Depression through the Second World War to peacetime. It is difficult to write about those times and places without indulging in sentimentality. Yet that such a contained area could produce the likes of Glenn Gould, Doris McCarthy, Norman Jewison, Robert Fulford, Jack Kent Cooke, Ted Reeves, Bruce Kidd, and other contributors to the Canadian fabric surely points to that “something special about the Beach” that is oft cited by former residents. There are hundreds of others not mentioned specifically here with whom I interacted. This is a celebration of their lives, as well.

It is my hope that this description of the intersection of a unique setting, a mixed historical era, and one family’s story will show how the places in which we are nurtured influence the people we become. The details may be personal, but the implications are universal.